Tracy Wuster

When computers learn how to make jokes, artists will be in serious trouble.

–Donald Barthelme, “Not Knowing”

Both Sharon McCoy and I have taken on E.B. White’s semi-famous warning that studying humor is like dissecting a frog. I have seen several versions of this saying:

Analysts have had their go at humor, and I have read some of this interpretative literature, but without being greatly instructed. Humor can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind.

Analyzing humor is like dissecting a frog. Few people are interested and the frog dies of it.[1]

Sharon nicely explains that the metaphor is off–frogs are already dead when they are dissected–and that the act of dissecting the frog leads to scientific understanding of not only frogs, but of ourselves and of our environment. In my post, I explained that White states this position, and then he goes on to offer some definitions of humor–partaking in a long tradition of people claiming you can’t define or discuss characteristics of humor and then going ahead and doing so. I call it a “definitional denial.”

What I think the prevalence of this quote points to is a larger fear that the study of literature–or of film, or of television, or of any piece of artistic expression–somehow seeks to lessen the experience of that object. That to seek to understand a cultural object is to lessen the authentic interaction one might have with that object. That to call something a “cultural object,” and to point out that it might have a historical or sociological or psychological or linguistic or any other academicalistic meaning, takes that thing out of the realm of enjoyment, of relaxation, of appreciation and then puts it into the realm of school. And with humor–which most people experience as enjoyment, as laughter–the feeling is either heightened or easier to vocalize. For those who didn’t get pleasure out of school, putting humor into the scholarly realm might be a heightened betrayal [2].

When encountering a frog, most people just want to watch it, not cut it open to see how it works.

But some of people like to think about how humor works. We are scholars. Just as there are scholars of frogs, and of schools, and of Texas music, and of male flight attendants, and of religion, and of stadiums, and of just about everything else, there are scholars of humor. And unless you don’t like scholars in general, there should be no need to defend any particular branch of study: from frogs to funny.

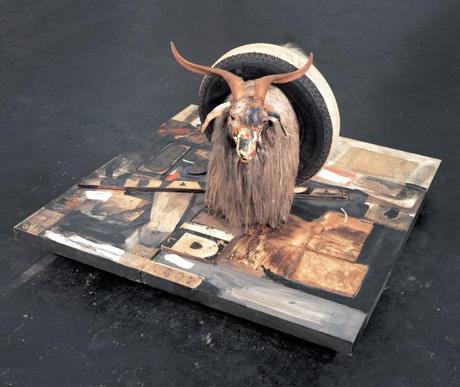

That being said, I seem to be venturing close to my a corollary form of the “definitional denial”: the defensive denial–claiming I don’t need to defend the study of humor and then doing so. Instead, let’s turn not to a dissecting a frog, which is not a terribly good metaphor for humanistic study of humor, to looking at a goat. Not just any goat. This goat:

Robert Rauschenberg, “Monogram” (1959)

A person off the street seeing this piece might have any number of reactions–”What does it mean?” ”Who is it by?” “is it supposed to be funny?” ”I like it” “I hate it” “eh” “wow” “is it art?” These reactions are not much different from the reactions people might have to a piece of humor more generally. Your answers to these questions, your reactions, matter to you. And the range of reactions a cultural object might have are important as evidence of audience reception.

But to the art historian, or the aficionado of art more broadly, the historical context of Rauschenberg’s combine matters, along with its formal characteristics and its place in his development as an artist.

For Donald Barthelme, in his great essay on writing, “Not Knowing,” [3] Rauschenberg’s goat stands in as a synecdoche for all prose and poetry, really all art. It is an object deliberately made, presumably meaningful in some way, and one that inspires explanation. In other words, it is an object of study (for those interested in that study, of course).

As an object of study, the goat with the tire inspires similar responses to humorous objects and might itself be a humorous object. Is it worth studying? What can we get from studying it? What does it say about the artist, about its time, about art more generally? Will studying the goat kill our enjoyment of the goat?

The goat–like the frog–was already dead. The metaphor of art as “living” or “dead” only goes so far. As Barthelme writes, the goal of mimesis–of representing the reality of the world–has become an impossible, or at least impractical, goal for the writer, and we might instead see the text as “an object in the world rather than a representation of the world.” For Barthelme, and I think I would follow him on this path, art is “always a meditation upon external reality rather than a representation of external reality or a jackleg attempt to ‘be’ external reality.”

The confusion comes when individuals are confronted with an object and it becomes part of their own external reality–often and object of art becomes vital to an individual. With humor, something makes us laugh, and that object becomes a living thing, or more precisely, part of our lived experience.

And this transaction is somewhat magical. The problem with study is the fear that this magic will be explained, that the living experience will become the dead object, that the fun will be sucked out and we will be tested on a corpse. And, surely, sometimes this happens. But, I would argue, that the problem is not the act of study, but the method: with my students, I find that I must frame the study of literature (or art, or other cultural object) not as a problem to be solved but as an experienced to be deepened. The end goal of interpretation is not to answer something like an equation but to more fully understand a piece of literature and, often, the time period in which it was produced. Admittedly, the study of humor will still change our experience of the object, but most humor scholars aim for the experience to make individual objects of humor more alive and, as an extension, to enliven the experience of all humor.

That is surely a lofty goal, and one easier stated than accomplished. Not everyone who dissects a frog will learn much about the creature, and not everyone who sees Rauschenberg’s goat will think about it in any depth–even if asked to.

Barthelme takes on a kind of “critical imperialism” in which a “tyranny of great expectations obtains, a rage for final explanations, a refusal to allow a work that mystery which is essential to it.” The range of approaches to literary works (as well as other artistic works) that, in one way or another, reduces the work to a system, to straightforward evidence of a cultural zeitgeist, to a footnote in some larger project of representing reality–these are the approaches that risk extinguishing the vitality of the work of art.

Not that these approaches might not create something vital in their own right… but that the mystery of the literary work might disappear as critics seek other mysteries. Then the critical work is no longer about the goat but about the world in which the goat is an object. Far be it from me to state the proper subject for study, as I said earlier, study what you will–from frogs to funny. But with humor, the vitality of the interaction between the object and its audience seems so central that the movement away from that magical moment of surprise seems more an act of killing than it might in other cases.

But, remember, the goat was already dead and stuffed when Rauschenberg put that tire around it. Those interested in understanding the work might follow Barthelme’s line of analysis:

What precisely is it in the coming together of goat and tire that is magical? It’s not the surprise of seeing the goat attired, although that’s part of it. One might say, for example, that the tire contests the goat, contradicts the goat, as a mode of being, even that the tire reproaches the goat, in some sense. On the simplest punning level, the goat is tired. Or that the unfortunate tire has been caught by the goat, which has been fishing in the Hudson–goats eat anything, as everyone knows–or that the goat is being consumed by the tire; it’s outside, after all, the mechanization takes command.

After some further discussion of possibilities, Barthelme writes that “what is magical about the object is that it at once invites and resists interpretation. Its artistic worth is measurable by the degree to which it remains, after interpretation, vital–no interpretation or cardiopulmonary push-pull can exhaust or empty it.” The best interpretations of humor, I would argue, help us understand the vitality of humor, either by providing an understanding of the ecosystem of a living joke or by revitalizing humor that has become a taxidermied specimen in need of some contextualization.

I have gotten far back into the metaphor of the study of humor as something of a natural science. That link between humor and a living creature seems important. As Simon Critchley points out in On Humour, the link between animal and human is a key aspect of humor:

If humor is human, then it also, curiously, marks the limit of the human. Or, better, humor explores what it means to be human by moving back and forth across the frontier that separates humanity of animality, thereby making it unstable…

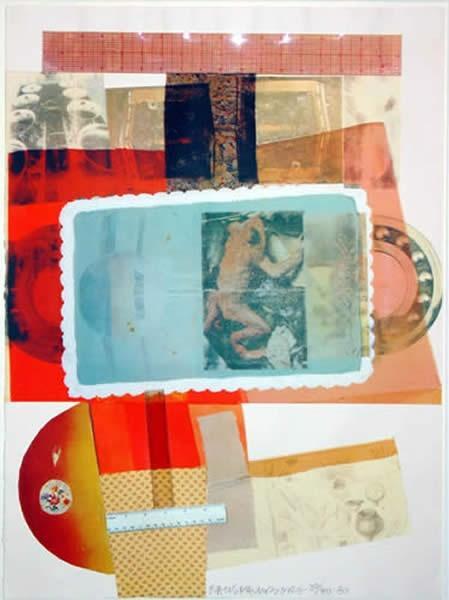

This link might explain the sudden explosion of videos on my Facebook page featuring goats screaming like humans (a video of which has been viewed over 16 million times). Animals-real and imagined–acting like humans has long been a staple of humor that would be worth considering in more depth. But this study should never kill the vitality of watching a kitten scamper, a blue jay think, or a rabbit sing [4]. Or, we might take a look at Rauschenberg’s view of the frog:

(c) 2013, Tracy Wuster

Notes:

[1] Note: he does not say that explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog, although the quote sometimes gets bastardized into this formulation. Very few humor scholars are out there explaining jokes the way people like to imagine when they use this quote.

[2] White’s formulation speaks to those who want to make something funny–to produce humor–as a living thing. To write something that could someday be anthologized with Mark Twain’s great jumping frog. Elsewhere, White wrote to William Zinsser: “But if you’re hoping to disabuse people of the notion that there is something vaguely second-rate about humorous expression in literature, I wish you luck. I don’t think you have a prayer.”

[3] See a class project on Barthelme’s essay that inspired this post:

http://dbknowing.blogspot.com/

http://dbnot-knowing.blogspot.com/2012/05/alpha.html

[4] My original goal was to relate Barthelme’s discussion of the goat with this video:

Nature industrialized. Violence mechanized. Sheep absconded and rescued. The wolf outfoxed. Framed by the cohabitation of natural enemies who clock in to the “factory” of a field of sheep, Ralph E. Wolf is foiled by an increasingly implausible resolutions to his plans. Maybe for another day…