In this week's edition of the American Heart Association medical journal, Circulation, Dr. Rachel Lampert and her colleagues from Yale University School of Medicine published a report entitled "Safety of Sports for Athletes with Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators." This report is important because it is the most careful description yet of what happens to athletes with these devices who continue to participate in sports.

Background

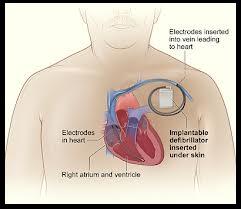

Internal cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are sophisticated medical devices that are implanted near the heart, usually with leads (electrodes) that are threaded into the heart, and are designed to provide a shock in the event that its owner's heart develops a fatal arrhythmia. You can read more about the ICD and view some diagrams that show how these devices are implanted in an article by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

These ICD devices are a treatment for patients who have had--or who are at high risk for--sudden cardiac death (SCD), the abrupt onset of a fatal arrhythmia. From the new report, the list of reasons that subjects had received an ICD was pretty long, and included: long Q-T syndrome, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD), coronary artery disease (CAD), idiopathic arrhythmias in a structurally normal heart, dilated cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, and valvular heart disease, among others.

Conventional wisdom has held that athletes with an ICD should be restricted to low-intensity sports such as golf. Consensus guidelines for athletes with an ICD are summarized in the Proceedings of the 36th Bethesda Conference on Eligibility Recommendations for Competitive Athletes with Cardiovascular Abnormalities. These cautious guidelines stemmed primarily from a concerns about 1) the efficacy of the ICDs to deliver a shock appropriately during intense exercise and 2) the possibility of damage to the device or leads during physical contact that might render the device ineffective.

Interestingly, in 2006 these same investigators conducted a survey of Heart Rhythm Society members and found that more than 40% of respondents reported having at least 1 athlete patient with an ICD who was continuing to participate in competitive or vigorous sports despite recommendations to the contrary.

The Study

In 2006 the investigators started a registry that would enroll and follow athletes with an ICD who were known to be continuing to participate in sports of moderate or high intensity. Often, this would be a situation where the athlete patient was participating in these sports despite their doctor's recommendation not to do so. The investigators eventually enrolled 372 athletes. Of these, 211 were enrolled by medical institutions in the United States (41) or Europe (16). The remaining 161 were self-enrolled--that is, the athlete contacted the Yale investigators directly and asked to be enrolled. The median age was 33 years and 33% were female.

The median follow-up was 31 months. Twenty-one patients did not complete the study: 9 were lost to follow-up, 6 withdrew, 4 stopped exercising because of worsening heart problems, and 2 died.

The important findings were:

1. There were no occurrences of death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, or arrhythmia- or shock-related injury during sports.

2. Thirty-six individuals (10% of the athletes studied) had shocks during practice or competition. Of these, 30% stopped participating in 1 or more sports as a result.

3. Twenty-nine individuals (8% of the athletes studied) had shocks during other physical activity. Twenty-three individuals (6% of the athletes studied) had shocks at rest.

4. There were 13 definite and 14 possible lead malfunctions and no generator malfunctions. This lead malfunction rate is similar to non-athlete populations.

5. There were no significant athlete injuries stemming from shocks during exercise.

My Thoughts

Creating this ICD registry was a great idea.

This report offers the most detailed look yet at what happens when athletes with an ICD continue to participate in sports. The results provide a basis for thoughtful conversation between physician and athlete-patient regarding the risks of continued sports participation with an ICD.

Although a small number of athletes experienced both appropriate and inappropriate shocks, it should be reassuring that the ICDs terminated all episodes of ventricular arrhythmias and there were no athlete deaths. Although it certainly remains a possibility, it is fortunate that there were no significant injurties to athletes receiving a shock during exercise. This is an area, though, where due caution is still well-advised because circumstances could be unforgiving for even a brief period of unconsciousness in activities such as cycling, rock climbing, swimming, etc. Lastly, the results suggesting that generator and lead malfunction are uncommon, even among athletes who were participating in sports that involve physical contact should allay fears that the ICD could be rendered inoperative during sporting activities.

My congratulations to Dr. Lampert and her colleagues!