My wife has a Masters Degree in French law and has worked extensively as a French political advisor. She's explained that in her experience many politicians make their decisions based on the data they receive ... except ... if there is a minor but highly political issue that the public is responsive to, they often take the opportunity to use this as a smokescreen to distract the public while the real work happens behind the scenes. In that case, the politician is often in a position of having to respond to public perception and this may very well not be in synch with the data. For example, I have been reading a British immigration report from July of 2000 which showed fairly conclusively that both skilled and unskilled migrant immigration was beneficial to the UK economy yet UK immigration has been capped at 20,700 (non-EU) immigrants, despite internal reports making it very clear that this does not satisfy market needs. However, it does satisfy political needs.

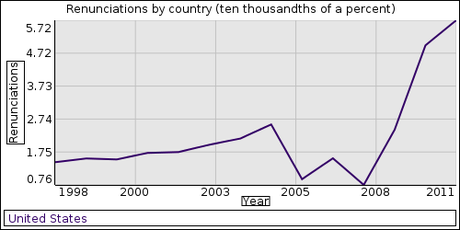

So let's step back from the politics and look at the numbers. Here are US renunciations since 1998 (the published data starts in 1997, but that year is rather anomalous and I'm not including it until I better understand what is going on):

Source. This data matches my own research, but until

I have generated my own numbers, I will rely on this.

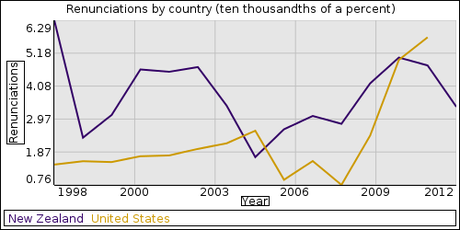

Out of curiosity, I've decided to try to find out the renunciation rates of other countries. The only other country I've been able to get data on is New Zealand. Their Department of Internal Affairs for the Citizenship office graciously sent me their total number of renunciants per year and the highest total was 24 for 1998. However, they have a much smaller population than the US, so I again calculated the percentages (note that both US and New Zealand percentages are calculated against the correct yearly population):

Source: information received via email from the Department of

Internal Affairs of the New Zealand Citizenship Office.

2012 renunciation data is obviously "Year to Date"

As you can see, the numbers aren't terribly different. However, we can't conclude much from this because there are several pieces of information we don't have. For example, like the US, New Zealand only tracks renunciants who have formally renounced. Thus, we don't know who may have indirectly given up citizenship by acquiring another "exclusive" citizenship. However, unlike the US, there is no legal incentive to give up citizenship because they don't have the United State's unique citizen-based taxation. Thus, it's very likely that the graph above represents a comparison of US voluntary and involuntary renunciations versus New Zealand's involuntary renunciations (due to taking citizenship in a country that forbids dual citizenship).

I would love to find more information like this. I've filed a Freedom of Information Request with the UK government and hope to have an answer in a few weeks (the answer is very likely to be "we don't know" if they don't track this data). If any readers can find this information for other countries, along with a source, I would be very grateful.

My ad-hoc method of research into this topic reveals four primary categories of renunciations:

- Politicians for whom dual-citizenship is a political liability.

- People escaping from oppressive regimes.

- People acquiring citizenship in countries that forbid multiple nationalities.

- Americans.

Unfortunately, because I've only been able to get the data for New Zealand and the US, I can't prove my suspicions, particularly since they don't appear to match the New Zealand data.

I'm quite confident there would be a taxpayer revolt in the US if they had to face the onerous tax requirements that American expats face. However, we expats are out of sight and thus out of mind. Further, we have no political power in the US and politicians happy to flog populist anger and improve their poll ratings at our expense.

And in case you're wondering why US expats care when we often owe no US taxes: it can easily cost us $1,000 just to file a tax return. The lowest price I've seen from a reputable expatriate tax return firm is $300 for the 1040, Schedule B, Form 2555 and Form 1116. And that assumes that you have the simplest possible taxes, have only earned income (that's a very specific legal term) and don't have to pay for notarized translations of foreign financial documents. If you were unaware of your expatriate tax obligations, you can easily pay $16,000 to enter the OVDI program and that still doesn't eliminate fines and possible criminal charges for being unaware of your legal obligations to the IRS. You try to explain to an American teacher in Uganda who's struggling to pay her rent why this is fair.