New research into current human evolution has identified many attributes in Homo sapiens which are still evolving, including female height, undermining the idea that the advent of civilisation has stopped evolution in its track.

New research into current human evolution has identified many attributes in Homo sapiens which are still evolving, including female height, undermining the idea that the advent of civilisation has stopped evolution in its track.

This research – undertaken by an international team of scientists led by Dr Stearns of Yale – also provides yet more confirmation of the niche construction hypothesis, which I’m a big fan of; a fact you may have picked up on given I’ve written about it a lot. For those of you just joining us (EvoAnth recently obtained 300 followers, celebration suggestions welcome) and too lazy to click on links to prior posts, niche construction is the idea that some animals – including humans – create their own unique environment. Since this is a new “niche” it means we will be exposed to new evolutionary pressures and thus continue to evolve.

I need a picture of Darwin happy to be vindicated yet again

I particularly like it because it’s so common sense yet almost always overlooked. The vast majority of people who talk about current human evolution believe that living in safe cities has stopped it, bemoaning how our modern lifestyle is “unnatural” and should be stopped. Because, dammit, if most of the population aren’t dying off to benefit the gene pool then what is the point of it all? Of course, this is completely forgetting these “safe cities” are a brand new environment for us to adapt to meaning evolution will in fact continue.

Dr Stearn et al. confirmed this by analysing data obtained during the “Framingham Heart Study” which examined 5209 people (and their children) every 2 years since 1948. During that period they had children, and those children had children, providing information on how various traits increase reproductive fitness and spread throughout the population (i.e. evolve). As an aside, the last generation was not included in the analysis since “many have not completed reproduction,” an amusingly detached and scientific turn of phrase.

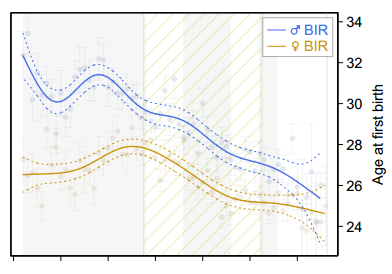

Their work revealed that originally being tall was beneficial to women, increasing the survival rate of their children. However, over time being shorter became better since short women can have children earlier, increasing the overall number of children they have. This resulted in shortness becoming more common in subsequent generations (i.e. evolution!). Dr Stern et al. hypothesise that this shift occurred because advances in medicine meant that infant survivability was no longer an issue: doctors could save a child regardless of the height of the mother. As such being more fertile (i.e. shorter) became more beneficial as it meant you could have more children. Since this is the result of humans making their own environment this is a textbook example of niche construction.

A graph showing age at first birth over time. X-axis is time

However, Dr Stearn et al.’s research into female height didn’t set out to examine niche construction theory. Rather, they were looking at sexually antagonistic selection. That is fascinating in its own right so I thought I’ll talk a bit about it here. Apologies for luring those of you who just wanted to read about current human evolution into a science lesson but I hope you’ll find it interesting nonetheless.

Sexually antagonistic selection is based on the fact that autosomal genes (genes not on the sex chromosomes) will spend around half their time in males and half their time in females. Unfortunately the same gene might not be beneficial in both men and women meaning it will only increase the fitness of an individual 50% of the time. This slows down the rate at which natural selection will spread this trait throughout the population, slowing down the evolution of the species. You’d think this is a pretty big deal, but nobody has examined to see whether it is occurring in humans (until now)!

I have no more relevant images so here is a grumpy cat, reflecting my annoyance at the lack of colourful pictures in the research.

In fact, a gene which is beneficial in one gender might be downright harmful in the other! However, as long as the net effect of the gene is positive (i.e. the benefits gained by one gender outweigh the cost to the other) the gene will still spread throughout the population. Albeit slowly. Until a new regulatory gene emerges which ensures that the trait only occurs in the gender who benefits from it one gender will continue to suffer and natural selection of the trait will be reduced.

They noted that height appears to be under the influence of sexually antagonistic selection. As was already mentioned, evolution is favouring shorter women but isn’t selecting for shorter men. Or taller men. In fact diverging from the average male height appears to decrease their fitness, thus maintaining the status quo. As such a gene which results in a shorter individual is only going to be beneficial in females and will thus be influenced by sexually antagonistic selection.

This research seems to be reliable since they’re examining whether traits actually increase chances of reproduction rather than simply hypothesising whether a trait results in greater reproduction. As such they’re less likely to be wrong. One of the leading criticisms of evolutionary psychology is that it does far too much of the latter, a critique this research escapes. That said, one potential source of error is that the sample size is demographically limited – the vast majority of people studied were of European descent. However, this just means we can’t extrapolate these results to the entirety of humanity, not that the results themselves are invalid.

In short we have a reliable study revealing that being small gives women a reproductive benefit by allowing them to start reproducing earlier. As such natural selection has spread this trait throughout the population. However, evolution isn’t that simple and this trait appears to be under the influence of sexually antagonistic selection, offering a disadvantage to men who have the same genes. Evolution: being difficult since 1859.

Stearns SC, Govindaraju DR, Ewbank D, & Byars SG (2012). Constraints on the coevolution of contemporary human males and females. Proceedings. Biological sciences / The Royal Society, 279 (1748), 4836-44 PMID: 23034705