Why do people share food? The obvious answer is because if we didn’t we would die. An average hunter-gatherer will only be able to kill one large animal a month (Hakwe et al., 1991). Although this might keep them fed for a week, during the other 3 they’ll starve to death. However, by sharing your kill with other members of the tribe you encourage them to return the favour, ensuring you don’t go hungry during your dry spell.

If sharing is key to our survival then pizzas are arguably the pinnacle of evolution

At least, this is the logical reason we should share food. However, humans are famously illogical and in many ways we don’t act like reciprocity is the main reason we share food. For example, if we’re trading food now for food later we might expect better hunters (who are able to share more food with the group) to receive more food in return. But they don’t. Pretty much every member of a tribe, no matter how much food they share with others, gets an equal amount in return.

This is perhaps where the romanticised notion of hunter-gatherers as “egalitarian” came from. They don’t care about ownership, property and debt, just helping one another! Except they don’t really behave like this either. If a Haza hunter is seen with some food he’ll happily share it with the tribe. However, they’ll go to extreme lengths to ensure they aren’t seen with the food and so don’t have to share. One anthropologist even tells the story of how a hunter tried to hide their kill in his Land Rover so they could keep it for themselves (Marlowe, 2004)!

However, a new meta-analysis suggests that reciprocity is in fact one of the primary reasons we share food. So why do bad hunters still get lots of food? The answer seems to be that people base their food sharing decisions on the long-term relationship. Bill may only have given me 1kg of food this month, but he’s been giving me 10kg a month for the past year. So this month I’m still going to give him 10kg of my food.

The other reason bad hunters get fed is because people share more than food. Bill may have only given me a bit of food, but he helped repair my spear. So I’m still going to give him a lot of food. The “currency” used varied, but the fact the relationships were reciprocal didn’t.

This meta-analysis also identified two other important reasons people share food: kin selection and tolerated theft. Close relatives share some of your genes, so by helping them you’re indirectly helping your genes flourish (kin selection). Meanwhile tolerated theft is the idea that you won’t be able to eat all of your kill before it rots, so you might as well allow others to have some. You don’t loose anything and might get some new friends out of it!

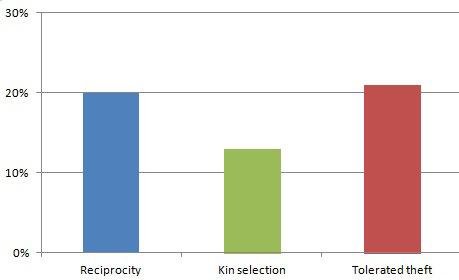

The amount of food sharing that could be explained by the 3 motivations. Note: sometimes food sharing was done with multiple motivations, so the total amount of food sharing these explain (~49%) is lower than adding them up individually

Taken together these 3 reasons explain about half of all food-sharing amongst hunter-gatherers. Although this means there are additional reasons people share food, it seems reciprocity, kin selection and tolerated theft are all very important.

However, the fact there are additional, mysterious forces at work here isn’t the most interesting conclusion of this meta-analysis. What’s much more interesting is the fact they also examined studies of food sharing amongst non-human primates and found they were sharing food for the same reasons people were. Reciprocity, kin selection and tolerated theft were just as likely to motivate monkeys, apes and humans to share their food (Jaeggi and Gurven, 2013).

This is particularly significant because reciprocal sharing is quite a complex behavior. You have to remember who has given you what, who you owe food to and so on. As such, some researchers have argued that many species of primate simply weren’t smart enough to engage in reciprocal sharing (Hauser, 2004). Although it may well be an intellectually demanding behaviour, this analysis shows that even small-brained monkeys are still smart enough to reciprocate (Jaeggi and Gurven, 2013).

This also raises some interesting evolutionary implications, suggesting our more ape-like ancestors were still motivated to share by the same things that motivate us today. It would seem greed (reciprocity), love of family and laziness (tolerated theft) have been human traits for a very long time!

References

Hauser, S. 2004 Why be nice? Psychological constraints on the evolution of cooperation. Trends in Cognitive Science. 8, 60 – 65

Hawkes, K., O’connell, J. F., Jones, N. B., Oftedal, O. T., & Blumenschine, R. J. (1991). Hunting income patterns among the Hadza: big game, common goods, foraging goals and the evolution of the human diet [and discussion].Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 334(1270), 243-251.

Jaeggi, A. V., & Gurven, M. (2013). Reciprocity explains food sharing in humans and other primates independent of kin selection and tolerated scrounging: a phylogenetic meta-analysis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1768).

Marlowe, F. W. (2004). What explains Hadza food sharing?. Research in economic Anthropology, 23, 69-88.