Be careful, it’s Vegas out there

The cavernous room is lit in a dim, yet pleasing way. There are no windows, no clocks, no reminders of the outside world. It could be noon or it could be midnight outside. In here, there’s always time for one more round.

In front of you, a machine flashes like a video game. You watch the simulated wheels turn quickly at first and then they slow, one by one. The first wheel lands on the letter “W.” The next stops at “I.” The last rolls excruciatingly forward, passing worthless letter after worthless letter until you see the one you’ve been waiting for.

The letter “N” appears at the top of the screen and begins to move its way down toward the jackpot position. You watch as it slides ever so slowly toward the thing you’ve been playing for all night: WIN. You see that word completed on the screen for just an instant before the N ticks once more, out of position and back to worthlessness. You almost won big. Or so you think. In reality, you’ve just been manipulated.

Many years ago I recall reading about the incredible amount of planning that goes into making slot machines as addictive as possible. Their lights and bells are meticulously calibrated to keep you in a perpetual state of agitated excitement. The payouts are statistically measured and timed to give you just enough reward so that you keep on playing. And every once in a while, just often enough according to the latest behavioral science, the machine will let you think you almost won the big jackpot. How can you stop playing now when you were oh so close to cashing in?

It’s all carefully choreographed to relieve you of as much of your money as possible. Now those same tricks and tactics are coming to a website near you.

It’s funny, in an ironic kind of way. The internet has put all the world’s information at our fingertips. In exchange, we give the internet little bits of information about ourselves. At first that exchange was unambiguously to our advantage. But those little bits of data we hand over with every click and transaction are accumulating into frighteningly accurate portraits of our personal lives. Moreover, this deep knowledge about our habits and behaviors is giving surprising power to people we’ll never meet.

The New York Times ran a fascinating article about how the large retail chain, Target, used its database to predict which of its customers were pregnant.

Target “was able to identify about 25 products that, when analyzed together, allowed them to assign each shopper a “pregnancy prediction” score. More important, they could also estimate her due date to within a small window, so Target could send coupons timed to very specific stages of her pregnancy.”

Of course, not all pregnancies are perceived as bundles of joy. Some are even kept secret; at least from those closest to us. Just not from faceless retailers whose constant barrage of baby related promotions to a teenage girl sent her father into a rage.

“My daughter got this in the mail!” he said to a Target store manager according to The Times. “She’s still in high school, and you’re sending her coupons for baby clothes and cribs? Are you trying to encourage her to get pregnant?”

Oops. Target apparently thought that train had already left the station. And it probably had.

That incident happened more than two years go. It’s safe to assume that the sophistication of Target’s data collection and analysis have grown at least as fast as technological progress more generally, which is to say extraordinarily fast.

In the same way that slot machines have evolved over the years from simple mechanical devices into manipulative supercomputers, modern marketing has moved beyond mass mailings and even targeted promotions to something that seems a bit more exploitive.

If you’re like me, you’ve probably grown accustomed to seeing ads pop up for things you’ve recently searched for online. When I looked at some camera equipment on Amazon a couple weeks back I wasn’t terribly surprised to find other unrelated websites promoting the same gear.

But that tactic is downright passive compared to what’s been happening more recently. Instead of just deluging me with ads for products I’ve researched online I’m not getting offered discounts on those same products, but with an important catch. The discounts are only valid if I spend more than I originally planned.

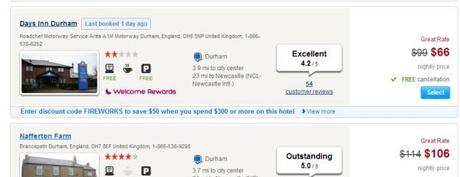

Hotels.com discount codes are carefully calibrated to get you to spend more money

Hotels.com has done this to me in both general and very specific ways. They know quite a bit about my travel habits; how often I book hotels, how long I normally stay, and how much I typically spend. So do you think it was a coincidence that they offered me a discount coupon valid for bookings that cost just a bit more than my ordinary hotel budget?

It could have been, I guess, except that they did the same thing to me again only in a slightly different way. This time I had just completed searching for a hotel for four nights in Durham England. Along with the listing of available rooms Hotels.com offered up a promotion code for $50 off a stay at the Days Inn.

It seemed like a good deal until I clicked through to discover that the code required a purchase of $300 or more. Meanwhile my booking for that hotel would total just $264. I wouldn’t be able to use the discount unless I stayed an extra night. But if I extended my stay, I’d get that extra night nearly free.

I was so, so close to a really good deal. How could I stop now?

The similarities to the way slot machines manipulate people floored me.

In both cases Hotels was trying to induce me to spend more than I typically would. They figure, probably correctly, that if they can get me to spend a bit more than I’m used to, I’ll enjoy that higher spending level and make it my normal budget. And you can bet that once I’ve raised my spending threshold, I’ll receive even more promotions making those just slightly out of reach purchases seem like can’t miss deals.

For this ploy to work, though, Hotels.com – or any company – needs to know an awful lot about my particular spending habits. Thanks to “Big Data” they know that, and a whole lot more.

Unfortunately it gets worse. Last week news broke that Facebook had successfully altered people’s moods by tampering with their news feeds.

For one week in January 2012, data scientists skewed what almost 700,000 Facebook users saw when they logged into its service. Some people were shown content with a preponderance of happy and positive words; some were shown content analyzed as sadder than average. And when the week was over, these manipulated users were more likely to post either especially positive or negative words themselves.”

Why, you might ask, is Facebook trying to make us sad? One possible explanation is the huge body of evidence that emotions play a critical roll in how we make our decisions, and especially how we make our buying decisions. How we “feel” about brands, about ourselves, whether we’re currently happy or sad all influences what we buy and how much we buy.

If Facebook can selectively shift how we feel, they can sell that capability to marketers. Instead of just pitching us stuff targeted to our specific interests, and inducing us with cleverly calibrated coupons, now they may be able to tailor these techniques to exploit the very moods they helped create.