Our prisons are called “correctional facilities.” Social science writer Daniel Goleman says this is “a tragic misnomer: nothing gets corrected.”

Our prisons are called “correctional facilities.” Social science writer Daniel Goleman says this is “a tragic misnomer: nothing gets corrected.”

Indeed, prisons are crime schools. Rather than being “corrected,” young inmates learn to emulate more hardened ones, their antisocial psychology is reinforced, and their criminal skills enhanced. No wonder most, after release, soon return.

Crime is stupendously costly to society. What criminals rip off is only the start. The damage to victims tends to vastly exceed their monetary loss; some never shake off the trauma. We lose what criminals could contribute were they instead productive citizens. The whole criminal justice system is another gigantic cost. As is running the prison system.

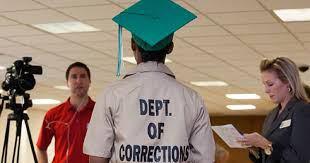

But what if prisons truly were places of “correction?” Of course, that concept does encompass the idea of punishment; but also the idea of changing the behavior that incurred the punishment. Our prisons do the former but not the latter.

Goleman’s book Social Intelligence discusses a special pilot program to fill this gap. “Brad” was in prison for injuring a college classmate during a drunken binge. “Basically all the guys are in here because of a bad temper,” Brad said – “easily pissed off” and ruled by their anger and an “us-versus-them paranoia.” The special program sought to change that mentality, giving inmates daily seminars on topics like “telling the difference between actions based on ‘creative thinking, stinking thinking, or no thinking.’”

It worked for Brad. Once released, he was a new man, returned to college, got a job, and detached from his previous loutish pals. Goleman also cites similar (and similarly rare) programs for social and emotional learning in schools that have likewise achieved big reductions in antisocial behavior.

(I’ve previously discussed Goleman’s writing about the “marshmallow test” for self-control and deferring gratification, so helpful for of adult life success, and how such positive traits can be taught.)

Programs like Brad’s would cost a tiny fraction (probably under 1%) of our huge prison budgets. Given the enormous cost of crime to society and the vast sums we spend locking people up, shouldn’t we be willing to spend 1% to keep them out of prison.*