Very quickly John Cole introduced me around and toured the entire facility with me, from stem to stern. One of the first things I recall in looking back is Dorothy Molander asking me how often I wanted to be paid. How often? Yes, she said, some of us like a weekly check, some twice monthly, whatever you’d like. I had never heard of anything like that before or since, and I quickly opted for a weekly check. After all, I was broke.

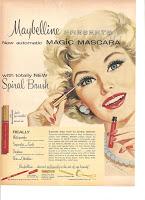

Right after I started our Assembly Supervisor, Hazel Peterson, retired. It was just a coincidence but it put that part of the operation in a new and untested direction. Even though I was new, John asked me to “be the eyes and ears” of what would become the Production Department. All of this moved along while the brand-new “Magic Mascara” was giving all facets of the company plenty of challenges. The several suppliers of packaging and product components were on maximum output, and the private label contractor came on line very quickly after the aborted start on Maybelline premises. Juluis Wagman, Chief Chemist, had set this up across town, and a small private-label outfit called Munk Chemical Company. This arrangement not only worked for the moment, the relationship between Munk and Maybelline grew over the years to encompass many new products. You name it, if it was a liquid product Munk was in the picture. As Maybelline grew, so did Munk.

All of this moved along while the brand-new “Magic Mascara” was giving all facets of the company plenty of challenges. The several suppliers of packaging and product components were on maximum output, and the private label contractor came on line very quickly after the aborted start on Maybelline premises. Juluis Wagman, Chief Chemist, had set this up across town, and a small private-label outfit called Munk Chemical Company. This arrangement not only worked for the moment, the relationship between Munk and Maybelline grew over the years to encompass many new products. You name it, if it was a liquid product Munk was in the picture. As Maybelline grew, so did Munk. New products began to roll out in rapid succession. It seemed that we’d just about catch up to volume from one blockbuster and another one, even bigger, was coming down the pipeline.

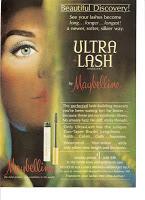

New products began to roll out in rapid succession. It seemed that we’d just about catch up to volume from one blockbuster and another one, even bigger, was coming down the pipeline. If we could single one over the others, it would have to be Ultra-Lash Mascara, with a newer applicator brush and formulation. We chased after that one for months before volume leveled out, at a very high volume that never went down. It had to be the prime money-maker for the company from roll-out to the Plough merger and beyond.

If we could single one over the others, it would have to be Ultra-Lash Mascara, with a newer applicator brush and formulation. We chased after that one for months before volume leveled out, at a very high volume that never went down. It had to be the prime money-maker for the company from roll-out to the Plough merger and beyond.

(NOTE: The “money-maker” reference above is speculation only. I was not privy to the company’s finances except to track direct labor production costs.)