While writing Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Twain had some trouble finding his flow. The manuscript was clearly important to him, and clearly troubling. His early mentions of it in letters are ecstatic — the writing was moving swiftly and clearly. But soon he hit snags. He ended up putting the manuscript away several times and writing three other books before it was finished. One of these books, Life on the Mississippi, has clear ties to Huck, but there are several significant scenes in his European travel “buddy” book, A Tramp Abroad, that also resonate strongly with his most famous novel. One of the funniest, and one of my favorites, involves crashing a raft.

Until this past Sunday, I had never really appreciated, except in a distant and intellectual way, Twain’s fascination with rivers. Even though I’ve been kayaking numerous times, and I’ve always had fun, I’ve never before tackled it with such a strong sense of my own mortality, the inscrutable flow of the current, and the exhilarating and hilarious terror of crashing. And now, frankly, I find myself even more puzzled by readings of the novel that focus on the idyl of the river, and see the tension and the terror coming solely from the society’s intrusions on that peace.

A river, really, is a fucking scary place.

Those moments of calm, drifting slowly along with the current, fill you with the delusion that you understand the flow, that you’ve surrendered to it, that it will in some way take care of you.

What utter horseshit.

The river is a powerful and inexorable force, utterly oblivious to your puny self, and it is best that you never forget that — at least while you’re actually still in its reach. It is just as happy to have you smash into a boulder as it is to have you flow gently and peacefully in its lullaby.

Heavy rainfall had changed the river that I thought I remembered. Our group had gotten spread out, and I learned of the second waterfall only when I saw a distant friend ahead suddenly disappear. Her head reappeared downriver, and I marked the spot I thought I had seen her navigate the hazard.

Boy, was I wrong.

Only when I was on the crest did I realize how poorly I’d chosen my spot. Looming right in front of me with remarkable insouciance was a gigantic fucking boulder, lying crosswise, right in my path. I turned the kayak as fast as I could, to try to shoot the narrow space between the bottom of the fall and the rock, congratulating myself when I succeeded.

Dumb.

As soon as I shot out of the ironic shelter of that rock, the full force of the river hit the kayak broadside, throwing me and all of what Huck would call my “traps” into the current. I got my head above water, and ducked again just in time to keep from getting brained by my own overturned boat, maniacally spinning its own dance in the current.

“A Deep and Tranquil Ecstasy”

Believe it or not, it wasn’t my life that passed before my eyes at that moment, it was this picture from Mark Twain’s A Tramp Abroad. (Twain scholars are truly weird people.) Here, the two friends sit blithely on their raft, with umbrellas to protect them from the sun, bathing their feet in the cooling water, and there is Sam, smoking away, like nothing will ever go wrong. But to me, now, it seems that there is a pensive gleam in his eyes, absent from his friend’s blank and vacuously smiling face.

As a child, Sam almost drowned in the Mississippi river numerous times. His brother Henry died on it, as did countless others he knew, and the slave trade was active up and down its waters. Mark Twain could have had no illusions about the ephemeral nature of the river’s idyll, whether the inevitable disruptions came from man or from the oblivious beast of the river itself. He had to be fully aware of the inevitability of the crash, of one’s helplessness in the current, of the hubris and strength with which we go against the current for a time or mistakenly believe we actually have control. Or peace.

In Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, the raft crash comes at a turning point in the novel. It is abrupt and terrifying, and it comes almost right after Huck has realized at last the magnitude of the crime he is committing by traveling with Jim. Further, he realizes at last that Jim has children of his own and an agenda of his own beyond helping this young white ragamuffin escape his father. But even then, Huck protects Jim from some slave catchers by telling them a lie, because Jim has praised him for being the only friend he has now, and for being “de on’y white genlman dat ever kep’ his promise to ole Jim” (124). But fog, the river, and a careless steamboat pilot result in a violent crash that separates them and changes the course of the novel.

In the complementary raft-crash scene of A Tramp Abroad, however, the moment is brief and fleeting — a minor but significant incident in the course of the novel. Here, in chapter nineteen, Twain’s narrator revels in his hubris and takes exuberant credit for the crash:

“An Excellent Pilot–Once!”

“I believed I could shoot the bridge myself, so I went to the forward triplet of logs and relieved the pilot of his pole and his responsibility.

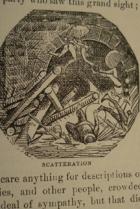

“Scatteration”

We went tearing along in a most exhilarating way, and I performed the delicate duties of my office very well indeed for a first attempt; but perceiving presently, that I really was going to shoot the bridge itself instead of the archway under it, I judiciously stepped ashore. The next moment I had my long coveted desire: I saw a raft wrecked. It hit the pier in the center and went all to smash and scatteration like a box of matches struck by lightning.”

The scene is brief and wickedly funny. Twain’s narrator reveals a “long coveted desire” — to see a raft smashed. He allegedly takes “responsibility,” but as soon as he realizes where the current and his own “delicate duties” with the pole are taking the raft, he deliberately disembarks, leaving his companions to their fate, which he describes with an “ecstasy” that is “deep,” but by no means “tranquil.” The story has holes, of course, and scholar James Leonard assures us that it happened only in Twain’s vivid imagination. If the raft were really “tearing along” in a “most exhilarating way,” there would be no way for the narrator to “step” ashore and stay dry; rather, he would have to dive from the raft.

Twain had undertaken this excursion during one of the periods in which his own flow on Adventures of Huckleberry Finn had been interrupted and the manuscript shelved. His own idyl interrupted, Twain cast about for new currents, and it is difficult for me not to read the complementary scene in A Tramp Abroad as a wicked satire on his own agency and covetous desires as an author, and his own uncertainty about where the crash in the shelved manuscript might lead him.

Hardly an idyl, surrendering to a river’s current means both joy and danger, both tragedy and absurdity. The crashes are sometimes life-changing or life-ending, and sometimes a minor bump in the road, a “scatteration,” a funny story to tell.

But it is all the same to the river.

© Sharon D. McCoy, 17 May 2013