In 1918, Charlie Chaplin completed work on his Sunset Boulevard film studio and released the first two movies - A Dog's Life and Shoulder Arms - of his eight-picture, one-million-dollar deal with First National. A Dog's Life, a 33-minute short about The Tramp first befriending a dog and then falling in love with a cabaret singer, was released in April. Shoulder Arms - a feature-length romp about The Tramp fighting for the French during WWI and capturing both the Kaiser and the Crown Prince - was released in October.

Why in the world am I talking about Charlie Chaplin!?! Who gives a lick about old silent films or when and where they were released? It's 2020 and COVID-19 is turning the world upside down! I mean, what am I even doing here?

The World Is Upside Down

The delayed so far: A Quiet Place II, Peter Rabbit 2, Fast & Furious 9, No Time to Die, Mulan, The Lovebirds, Blue Story, New Mutants, Antlers

The delayed so far: A Quiet Place II, Peter Rabbit 2, Fast & Furious 9, No Time to Die, Mulan, The Lovebirds, Blue Story, New Mutants, Antlers Here in America, Wall Street is partying like it's 1987, and not in the fun way either. All major sports, conventions, Broadway musicals, and concerts have been canceled or delayed and just about every new movie between now and the end of April has been pushed back indefinitely. Colleges and grade schools are gradually following suit. Italy, China, France, and other countries instituting similar and - in most cases - even more draconian lockdown measures merely sigh, "Welcome to the club, Yanks. What took you so long?"

Yet, as public gatherings of several hundred people or more are banned in county after county, city after city, and state after state, the movie theaters remain open, in some cases on a pure technicality. After all, if California says it's outlawing any public gatherings of 250 or more people your average AMC is within its rights to point out that none of its theaters feature rooms with that many seats. Hastily written industry trade reports about when or if the movie theaters will close feature quotes like: "This is an unprecedented situation."

That came from an unidentified industry veteran presumably speaking on background to The Hollywood Reporter' s Pamela McClintock.

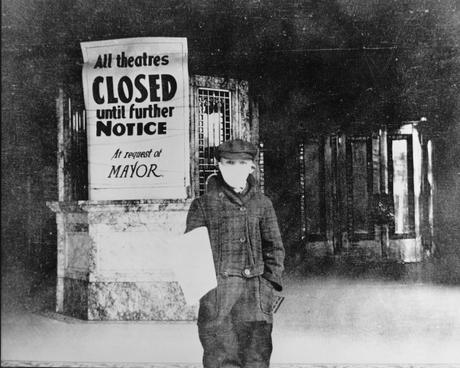

This, actually, isn't entirely unprecedented. Movie theaters have closed before due to disease. It happened as recently as a decade ago in Mexico when the nation's theaters and other public gathering places closed their doors for several weeks in response to the H1N1 swine flu, a measure now believed to have helped slow the spread of the disease. And it happened all around the world in 1918.

Which brings us back to Charlie Chaplin.

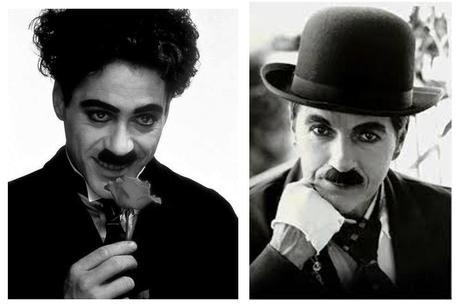

Ah, 1918 - a big year for Chaplin. Truly. In addition to the aforementioned movies, he also rather quietly married a 16-year-old actress who faked a pregnancy, later got pregnant for real, and bore him a son who died after a couple of days. Seriously, someone should make a biopic about this man.

Oh, wait. They already did.

Oh, wait. They already did.

But 1918 was also quite the horror show for millions around the world.

The forgotten carnage

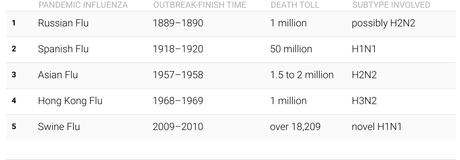

1918 witnessed the start of one of if not the worst pandemics in human history. The Spanish flu - so nicknamed despite most likely not actually originating in Spain - ultimately infected one in three people on Earth. Between the first recorded case on March 4, 1918 and the final case sometime in March 1920, Spanish flu killed 50-100 million people or 2.5-5% of the world's population. That we still don't have a more precise estimation over a century later speaks to how widespread the disease really was. It killed more people than World War I (17 million), possibly more than World War II (60 million), and maybe even more than both combined. For comparison, a subsequent pandemic - the 1968 Hong Kong Flu - killed 1 million worldwide and about 100,000 in the United State.

Source: South China Morning Post

Source: South China Morning Post

Yet, until COVID-19 nobody outside of the public health and history worlds ever really talked about the Spanish flu. There are no Spanish flu monuments in major cities around the world. It existed as a history book anecdote and the great bogeyman of world health, the "it could happen again" warning that always seemed to fall on deaf ears, possibly due to the boy who cried wolf syndrome. As someone who worked as a research assistant in a medical school's preventive medicine and public health department in 2009, I saw firsthand how quickly people greeted talk of pandemic with a hearty eye-roll:

Fear H1N1 because of that one time a long ass time ago when a lot of people died? Heard that one before with SARS. These things always go away. Modern medicine is too advanced to let a would-be pandemic get out of hand in the advanced world. Dustin Hoffman gonna get that damn monkey!

Have you seen this monkey? His name is Marcel and he belongs to a New York-based paleontologist named Ross Gellar. Also, he has some kind of disease.

Have you seen this monkey? His name is Marcel and he belongs to a New York-based paleontologist named Ross Gellar. Also, he has some kind of disease.

It's also a matter of timing and the way we tell our stories about history. The Spanish flu was at its absolute worst right as WWI was ending and ultimately couldn't stand up to the more easily digestible historical story of an assassinated Archduke with a funny name, trench warfare, and four long years of hell.

"WWI had a geographical focus (European and Middle Eastern theatres) and narrative that unfolded in time," Laura Spinney argues in her recent book Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed The World. "The Spanish flu, in contrast, engulfed the entire globe in the blink of an eye. Most of the death occurred in the thirteen weeks between mid-September and mid-December 1918. It was broad in space and narrow in time, compared to narrow, deep war."

Back to Chaplin again

So, when A Dog's Life came out America already had its first recorded case of Spanish flu. A soldier on a Kansas military base tested positive on March 11, 1918, but the news of the flu was censored in Allied and Central Powers nations so as not to depress wartime morale. Beyond that, the first wave of the Spanish flu was actually quite mild; it was the second wave - August-November - that proved to be the real killer. ( A similar pattern repeated itself decades later with the 1968 Hong Kong flu.) That means Shoulder Arms was released into a very different world than A Dog's Life.

As with COVID-19 now, by October 1918 public gatherings around the country were being canceled by the order of governors, mayors, and city health commissioners, never by the federal government. President Woodrow Wilson and his administration mostly pretended the whole thing wasn't happening, right up until the moment he got the Spanish flu himself while negotiating the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Lacking a top-down approach to mitigation, cities, and states had to fend for themselves. The result: wild inconsistencies across the board, with some cities closing movie theaters but not department stores, restaurants, or saloons, and other cities closing schools while others kept them open. In Arizona, one movie theater owner got so fed up he went into work and opened his doors to customers in defiance of local restrictions. He was promptly arrested, and when he challenged the case to the state Supreme Court - arguing the state didn't have the Constitutional authority to order the closure of his business - he lost. Similar legal cases played out in Wichita, Kansas, Tarra Haute, Indiana, and Roanoke, Virginia.

A decimated industry

As with now, the notion of closing all public gatherings was hotly debated, but closures ultimately became widespread. Photoplay estimated that "ten thousand picture theatres - 80% of the total in the United States and Canada - closed for a period varying from one week to two months." By mid-October, Variety reported that 90% of all American motion picture houses and live performances theaters had gone dark. An estimated 60% of all production activity in California ceased while virtually all of it ground to a halt on the East Coast. The loss in gross receipts due to closings was estimated at $40 million, or over $690 million in today's dollar, all of this according to the Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television

Unlike now, however, Broadway stayed open. On top of that, New York declined to close its schools or movie theaters. These decisions were not uncontroversial. New York City Health Commissioner Royal S. Copeland - an eye surgeon by trade who'd only been commissioner since April of the year - proved especially amenable to business concerns. He even allowed Woodrow Wilson to lead a parade of 25,000 people down Fifth Avenue on October 12, Columbus Day, a time when Spanish Flu was nearing it peak in the city.

The Spanish flu's second wave came to the US from the East Coast, through towns like Boston and Philadelphia, and their leaders eventually favored full lock-down measures. Copeland, however, preferred to stagger opening and closing times for businesses to minimize the number of people on the street at any one time, and partnered with the New York movie theaters to produce instructional slides about the flu and preceded each showing with a speaker educating the public about how to avoid getting the flu and what to do should they show symptoms.

(Other major cities that followed a similar strategy include Chicago, Detroit, Buffalo. One theater in Connecticut, according to the Hartford Courant, had a system in place where if anyone in the theater so much as coughed the film would immediately stop and the following text would be projected: "The person sneezing or coughing will please retire now in the interest of the health of those sitting near him. ")

Quietly, though, Copeland did close New York's "hole-in-the-wall moving picture shows" deemed unsanitary. The new movie palaces which had only recently risen to replace the old nickelodeons, however, stayed open since they not only seemed sanitary but were viewed as perfect venues for public health messaging. (Remember, this was way, way before TV or the internet.)

Chaplin, one last time

With those qualifications met, Manhattan's Strand Theatre kept chugging along. It was even referenced in the NY Times review of Chaplin's S houlder Arms: "'The fool's funny,' was the chuckling observation of one of those who saw Charlie Chaplin's new film. Shoulder Arms, at the Strand yesterday-and, apparently, that's the way everybody felt."

One of them paid for it though.

When Shoulder Arms was released on October 20, the manager of the Strand Theatre, Harold Edel, was quoted as saying: "We think it a most wonderful appreciation of Shoulder Arms that people should veritably take their lives in their hands to see it." Except that quote actually came from an interview he'd given week prior to the film's premiere. According to Pale Rider, once October 20th arrived, Edel wasn't in the theater. He'd died of the Spanish flu.

Someone seemingly making light of a pandemic promptly suffering its consequences? Sounds familiar. See also: Rudy Gobert, Matt Gaetz

In the grand scheme of things, of course, the death of one movie theater manager in 1918 wouldn't seem to matter. Still, Chaplin's Dog's Life greeted a world which didn't yet know any better whereas Shoulder Arms arrived at the peak of a pandemic. Copeland's public health strategy has received mixed historical grades, but in this particular case that theater owner didn't need to die.

Differences Between Then and Now

We've learned a lot since then, and we know that community mitigation efforts are all about buying time, delaying the influenza peak until a vaccine can be produced and minimizing the number of overall cases in order to provide relief to an overworked healthcare system. In such instances, social distancing measures combined with mass gathering modifications have been shown to be effective, e ven if some of the studies have been flawed.

When it comes to the who, when, and why of closing movie theaters and other public gatherings, the most recent Community Mitigation Guidelines published by the United States Department of Health and Human Service s advises:

Local decisions about NPI (non-pharmaceutical intervention) selection and timing involve consideration of overall pandemic severity and local conditions and require flexibility and possible modifications as the pandemic progresses and new information becomes available.

This is partially why AMC, Regal, Alamo Drafthouse, and the rest have been twisting in the wind here - sending assuring emails to loyal customers, limiting the number of employees in their building and assuring them of paid sick-leave, applying intense cleaning regimens, but ultimately deciding to stay open. As per the DHHS, these decisions are going to be made locally, and just as Copeland did in New York back in 1918 they could all decide to stay open.

And why not? COVID-19 and The Spanish flu are not the same. Their mortality rates - or at least the best mortality rates we can come up with for them right now - differ, with the former currently thought to be somewhere around 1% and the Spanish flu closer to 3%. Beyond that, COVID-19 is especially dangerous to the elderly and immunocompromised whereas more than half of the people killed by the Spanish flu were in the prime of their lives. We literally grade pandemics on a severity scale, and nothing has come close to ever matching the Spanish flu on that scale.

A Matter of Time?

Hollywood, however, sure seems like it's making this decision for the theaters. Can movie theaters really stay open if they have no new movies to show? We're not quite there yet. Not every single movie originally scheduled to open in the next two months has been delayed. Given the rate at which the situation is changing, though, more films seem likely to drop. You don't need a Royal S. Copeland to make the decision for you. The Disneys, Paramounts, MGMs, and Universals of the world are well on their way toward doing that for you.

A century ago the, decision making was mostly left to cities and states and businesses had to comply. That much is repeating itself again, and as movie theaters remain open even in some of the hardest-hit cities you wonder if the industry isn't already self-regulating itself at this point. No one is yet telling the theaters to close, but with Hollywood pulling just about everything off the release calendar the theater chains might be content-starved into closing.

Today, A Dog's Life and Shoulder Arms are in the public domain now. You can watch them online for free. Pretty soon, however, if theaters close and Hollywood scrambles for ways to make money some of these delayed movies could end up as online rentals. What a difference a century makes.

Sources: Public Health Reports, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, THR, American Pandemic: The Lost Worlds of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic, Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World , The United States Department of Health and Human Services, BMC Public Health