What is it Like to be a Bat? was a famous essay (I keep coming back to) by Philosopher Thomas Nagel. Its point being our difficulty in grasping — that is, constructing an intuitively coherent internal model of — the bat experience. Because it’s so alien to our own.

What is it Like to be a Bat? was a famous essay (I keep coming back to) by Philosopher Thomas Nagel. Its point being our difficulty in grasping — that is, constructing an intuitively coherent internal model of — the bat experience. Because it’s so alien to our own.

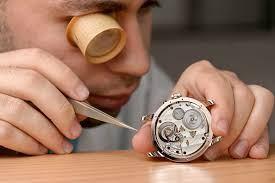

Biologist Richard Dawkins, though, actually tackles Nagel’s question in his book The Blind Watchmaker. The title refers to William Paley’s 1802 Natural Theology, once quite influential, arguing for what’s now called “intelligent design.” Paley said if you find a rock in the sand, its presence needs no explanation; but if you find a watch, that can only be explained by the existence of a watchmaker. And Paley likens the astonishing complexity of life forms to that watch.

However, it’s not mere “random chance,” as some who resist Darwinism mistakenly suppose.

It began with an agglomeration of molecules, a very simple naturally occurring structure, but having one crucial characteristic: a tendency to duplicate itself (using other molecules floating by). If such a thing arising seems improbable, realize it need only have occurred once. Because each duplicate would then be making more duplicates. Ad infinitum. And as they proliferate, slight variations accidentally creeping in (mutations) would make some better at staying in existence and replicating. That’s natural selection.

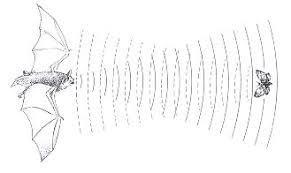

Dawkins discusses bats at length because the sophistication of their design (more properly, their adaptation) might seem great evidence for Paleyism.

Bats’ challenge is to function in the dark. Well, why didn’t they simply evolve for daytime? Because that territory was already well occupied, and there was a living to be made at night — for a creature able to cope with it.

Now get this. Their signals’ strength diminishes with the square of the distance, both going out and coming back. So the outgoing signals must be quite loud (fortunately beyond the range of human hearing) for the return echos to be detectable. But there’s a problem. To pick up the weak return echos, bat ears have to be extremely sensitive. But such sensitive ears would be wrecked by the loudness of the outgoing signals.

So what to do? Bats turn off their ears during each outgoing chirp, and turn them on again to catch each return echo. Ten to 200 times a second!

The foregoing might suggest, a la Nagel, that the bat experience is unfathomable. Our own vision seems a much simpler and better way of seeing the world. But not so fast. Dawkins explains that the two systems are really quite analogous. While bats use sound waves, we use light waves. However, it’s not as though we “see” the light directly. Both systems entail the brain doing a lot of processing and manipulation of incoming data to build a model of the outside environs. And the bat system does this about as well as ours.

A Paleyite would find it unimaginable that bat echolocation could have evolved without a designer. But what’s really hard for us to imagine is the immensity of time for a vast sequence of small changes accumulating to produce it.

Dogs evolved (with some human help) from wolves over just a few thousand years; indeed, with variations as different as Chihuahuas and Saint Bernards. And we’re scarcely capable of grasping the incommensurateness between those mere thousands of years and the many millions over which evolution operates.

Remember what natural selection entails. Small differences between two species-mates may be a matter of chance, but what happens next is not. A small difference can give one animal slightly better odds of reproducing. Repeat a thousand or a million times and those differences grow large; likewise a tiny reproductive advantage also compounds over time. It’s not a random process, but nor does it require an “intelligent designer.”

Returning to vision, a favorite argument of anti-evolutionists is that such a system’s “irreducible complexity” could never have evolved by small steps — because an incomplete eye would be useless. Dawkins eviscerates this foolish argument. Lots of people in fact have visual systems that are incomplete or defective in various ways, some with only 5% of normal vision. But for them, 5% is far better than zero!

The first simple living things were all blind. But “in the country of the blind the one-eyed man is king.” Even just having some primitive light-sensitive cells would have conferred a survival and reproductive advantage, better enabling their possessors to find food and avoid becoming food. And such light detectors would have gradually improved, by many tiny steps, over eons; each making a creature more likely to reproduce.

Indeed, a vision system — any vision system at all — is so advantageous that virtually all animals evolved one, not copying each other, but along separate evolutionary paths, resulting in a wide array of varying solutions to the problem — including bat echolocation, utilizing principles so different from ours.

But none actually reflects optimized “intelligent” design. Not what a half decent engineer or craftsman would have come up with. Instead, the evolution by tiny steps means that at each stage nature was constrained to work with what was already there; thus really (in computer lingo) a long sequence of “kludges.” For example, no rational designer would have bunched our optic nerve fibers in the front of the eye, creating a blind spot.

(To be continued)

* Some blind humans are actually learning to employ echolocation much like bats, using tongue clicks.

** This is not to say evolution entails slow steady change. Dawkins addresses the “controversy” between evolutionary “gradualists” and “punctuationists” who hypothesize change in bursts. Their differences are smaller than the words imply. Gradualists recognize rates of change vary (with periods of stasis); punctuationists recognize that evolutionary leaps don’t occur overnight. Both are firmly in the Darwinian camp.