Why tell this story now? That’s the thought I couldn’t get out of my head as I watched Trumbo, Bryan Cranston and Jay Roach’s new biopic of the famed Hollywood screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, who worked around the blacklist of the 1950s by masterminding a business arrangement allowing multiple blacklisted writers to pen scripts for B-movies as long as they agreed to have their work credited to a fake name. It is a story worth telling, and it will obviously be of significant interest to anyone interested in old Hollywood. Cranston’s performance certainly warrants the many awards nominations coming his way (read my review).

But you don’t tell this kind of story if you’re not trying to at least make some kind of commentary on contemporary themes, right? For example, Bridge of Spies isn’t just a Cold War drama about spies…on a brige; it’s also a comment on our on-going debate over what to do with prisoners suspected of terrorist activities. Going way back, Arthur Miller didn’t write The Crucible because he just really thought the Salem Witch Trials were super fascinating. He did it because he wanted to point to a tragic period in American history and draw parallels to what was happening in his world at that very moment, specifically the on-going actions of Senator Joseph McCarthy and the separate, but remarkably similar actions of The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The Crucible is an allegorical commentary on all of that; Trumbo is, ostensibly, a straight-forward telling of one man’s experience through that regrettable period of Hollywood history. However, what can we learn from his story? What is the modern day menace which deserves to be compared to the type of paranoia and fear-mongering which characterized the anti-communist actions of the 1950s?

The answer seems so obvious, yet I didn’t quite see it until Bryan Cranston pointed it out at a celebration recently organized by The Cinema Society:

“I think the story of Trumbo helps the public see how fearmongering can develop into a paralyzing experience for citizens. Incendiary comments that are only intended to stoke the fire aren’t helpful. Donald Trump is filled with inflammatory rhetoric, and I just think that he would say anything [be it demonizing all Muslims or slandering all Hispanics]. Look, he’s appealing to some of our most basic emotions through fear. And I think America is quite earnestly feeling that way. So the emotion is real. There are many aspects to Donald Trump. He’s a complicated guy, and I’ll be honest, an aspect that I like is that he is refreshing. I think people realize that he doesn’t have a filter, and he doesn’t even care if what he is saying is politically correct. For some reason at this moment in time, he is relevant in our political landscape. We need to learn from what he’s doing. Meaning that it’s time for us to adapt. And I think the bigger thing that I keep thinking about is, why are so many Americans responding to him?”

Of course, Donald Trump didn’t formally announce his presidential candidacy until June 16, 2015, a full seven months after Trumbo wrapped principle photography. Even though his candidacy had been an on-going rumor since 2011, it seems unlikely that Trumbo was actually made to warn us, “Sure, Donald Trump seems funny now, but that’s what everyone in Hollywood thought of HUAC at first. Then shit got real crazy real fast.” From a far more bottom-line point of view, it’s more likely that Trumbo’s real reason for being is tied to the success of the 2007 documentary of the same name.

It’s not exactly like Donald Trump’s political views and campaign promises are perfectly analogous to McCarthiasm, not the way the Salem Witch Trials were for Arthur Miller. Trump seems more interested in keeping people out (be they Syrian refugees or Mexicans at the border) than smoking out the supposed traitors in our midst. It’s simply a testament to the cyclical nature of America’s fear-based politics that someone like Trump has come along around the same time that Trumbo is in theaters.

It’s not exactly like Donald Trump’s political views and campaign promises are perfectly analogous to McCarthiasm, not the way the Salem Witch Trials were for Arthur Miller. Trump seems more interested in keeping people out (be they Syrian refugees or Mexicans at the border) than smoking out the supposed traitors in our midst. It’s simply a testament to the cyclical nature of America’s fear-based politics that someone like Trump has come along around the same time that Trumbo is in theaters.

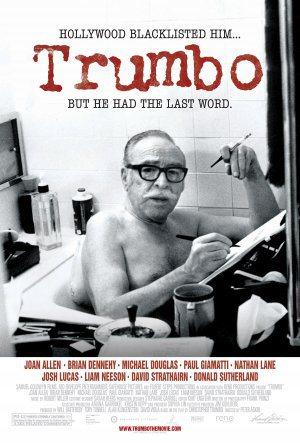

Cranston as Dalton Trumbo, and yes it is strange that his name just happens to be so similar to Donald Trump’s

Trumbo also seems to exist to remind us that the blacklist wasn’t as long ago as we think. The HUAC ultimately blacklisted over 300 people in Hollywood, and the overwhelming majority of them never managed to work their way back into the industry. However, there are those who still remember and feel its effects. For example, one of Bryan Cranston’s many stops on the promotional tour for Trumbo was The Late Late Show with James Corden on CBS. The fellow guest that night was Joseph Gordon-Levitt, there to promote his new Seth Rogen comedy, but it turns out his grandfather, Michael Gordon (Pillow Talk) was a film director who was actually blacklisted for the majority of the 50s:

Andrew O’hehir of Salon.com admitted in his write-up about Trumbo that if not for the blacklist he probably wouldn’t even exist. His mother, who worked on the legal defense team for Dalton Trumbo, probably wouldn’t have seen her marriage crumble under the stress of the blacklist meaning she wouldn’t have divorced and she wouldn’t have met O’hehir’s father.

Yet this isn’t Mad Men. It’s not like we can all watch Trumbo and then go to our grandparents and ask, “Wow, is that really how it was back then?” They probably wouldn’t know because, as O’hehir points out, “The material effects of the Hollywood blacklist were undeniably minor, and limited to people like Trumbo – a few hundred relatively privileged cultural workers who were marginalized and persecuted for their beliefs, or just for their associations.”

As Cranston said, Trumbo is ultimately the story of how “fearmongering can develop into a paralyzing experience for citizens.” This is a story which repeats itself throughout American history, from the Salem Witch Trials to the internment camps of World War II to the Second Red Scare of the ‘50s to Dick Cheney’s draconian post-9/11 rhetoric to the post-Paris paranoia of all Muslism. Because it is so cyclical it is helpful to be reminded of times when things went too far, and Trumbo serves that purpose while also delighting any film buff who might perk up when they hear titles like Roman Holiday and The Brave One referenced or see lookalike actors admirably standing in for John Wayne (who was a staunch conservative and one of Hollywood’s biggest HUAC cheerleaders) or Kirk Douglas (who defied the blacklist and hired Trumbo to write Spartacus).