Grief can be an awful thing. The loss of someone or something can dominate our lives for months, if not years, after the event. Surely – from an evolutionary perspective – such behavior can’t be beneficial. All the “wasted” time, effort and resources is hardly likely to improve our survival odds; and that’s not even counting the physical and mental harm that can stem from it. It must just be an unfortunate side effect of our emotional investment in people, pets and things (an emotional investment which is likely beneficial). However, a team of psychologists from Florida disagrees1. They’ve published research revealing that grief may have given our species an evolutionary advantage after all.

Their idea stems from the evolutionary phenomena of “costly signalling”. This is when an animal deliberately screws itself over; showing how great it must be to survive despite that disadvantage. The classic example of this is male peacocks, whose huge tails can hinder their movement and flight. If they can survive despite this (in fact, flourish despite this. The energy needed to sustain that tail isn’t insignificant) surely they have great genes and all the peahens should totally mate with them1.

Chimpanzee grief? An adult stands over a recently deceased child

Nature is full of examples of animals that have evolved a disadvantage to “show off”; increasing their evolutionary success in the long run. In this new study, the psychologists argue that grief may be a similar sort of emotional costly signal. If someone gets really upset when a relationship ends then clearly they invest a lot in their relationships; making them an excellent choice for a mate. Effectively, grief evolved as a sort of emotional peacocks tail; showing off just how much we care1.

Which is a nice idea, but is it right? If it was, one might expect people to have a higher opinion of those who exhibited more grief (as their peacock tail was more impressive). So the psychologists conducted a series of experiments to test this prediction; getting participants to read stories about people who had lost loved ones1.

They varied the severity of grief they expressed to see if it resulted in variation of how much people liked them. This ranged from simply describing “John’s wife died” to “John’s wife died and he grieved for 3 years” (with variation in between). They also varied it between third and first person (e.g. “my wife died”) to see if that had an effect. Finally, they got the participants to pick one of these people to be a partner in a trust game; seeing if the varying levels of grief influenced their decision1.

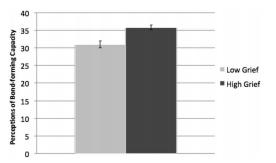

In every case the person who grieved more was viewed as a better person. They were ranked as more trustworthy, a more desirable friend, a nicer person, more loyal and having a greater capacity for forming emotional bonds. In short, grief did seem to act as a signal that the griever forms stronger relationships; making them a more desirable person to form said relationships with1.

How people viewed high and low grievers capacity for emotional bonds

That’s not to say we wouldn’t otherwise not feel any grief. Many animals exhibit behavior we might describe as grief, but it tends to be a lot less than what we experience. We evolved to grieve more than we perhaps should otherwise. But why did we have to evolve grief at all? After all, it still has many disadvantages. So why didn’t we instead evolve to lie about grief. Surely that would be an even better tactic? Perhaps, but it’s worth noting that humans are really good at spotting people lying about emotions2. Perhaps it was too hard to fake grief, forcing people to actually grieve instead.

So humans evolved an exaggerated sense of grief to show off how much they cared about people; highlighting their capacity for forming social bonds and establishing themselves as a good friend, partner, employee etc. Or so the authors of this research would like you to think. In reality there a few holes in this study that I think need to be rectified before we start talking about how grief is secretly great1.

For starters, they didn’t examine anyone who grieved too much. Sure, they looked at people who grieved too little for a particular occurrence (like someone’s twin sister dying, causing them to be a little upset) but none of the examples were people who cried for years over a carton of milk they spilled. If grief really was an indicator of strong relationships; surely people who grieved too much should be still be viewed very positively. Yet I suspect this might not be the case. There’s also the fact that – like most evolutionary psychology research – they only examined a very limited sample of humanity. Namely university students from Florida. Extrapolating from such a small sample to try and derive conclusions about the entirety of our species and our evolution seems a tad unjustified. Finally, there’s the fact that grief still has some negative side effects. For it to have evolved the beneficial consequences must outweigh these, yet this research does’t show this to be the case1.

In other words, this research establishes that grief may have social benefits in some populations; perhaps hinting the behavior has an evolutionary history. Maybe not the conclusion the psychologists wanted me to draw from their study; but hopefully they won’t spend too long mourning that fact.

References

- Reynolds, T., Winegard, B. M., Baumeister, R. F., & Maner, J. K. (2014). The Long Goodbye: A Test of Grief as a Social Signal.

- Ekman, P. (2003). Darwin, deception, and facial expression. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1000(1), 205-221