One of two sugar paste pavilions I made for an 'evocation' of Empress Maria Theresa's Feast of the Oath of Allegiance for the exhibition Imperial Privilege: Vienna Porcelain of Du Paquier, 1718–44, at the Metropollitan in New York

Over the past few decades I have attempted to recreate a considerable number of major period table layouts for museums and art collections in Britain, Europe and the US. These have usually been designed as vehicles for displaying important period tableware in the context of historically accurate meals. In 2009 I worked on a table at the Metropolitan Museum in New York based on the engraving below, which shows the Archduchess Maria Theresa enjoying an instalment feast in Vienna in 1740. I was invited to work on the installation by the exhibition curators Jeffrey Mungar and Meredith Chilton. Our version of the Archduchess's table was laid out with an extraordinary array of du Paquier porcelain from the period. It was dominated by two sugar paste baroque baldacchini, which I based on those depicted in the engraving. These were filled with pyramids of paper and sugar flowers as in the engraving. But it must be understood that even the Metropolitan Museum could not fully muster the resources to make an exact replica of a table from this lofty imperial level. To quote from Meredith Chilton, our version was more of an evocation than a recreation.

| The Feast of the Oath of Allegiance, Vienna, November 22nd 1740. Engraved from a drawing by Andreas Felix Altomonte (1699-1780) in Kriegl, Georg Christina. Erb-Huldigung welche... Mariae Theresiae... Als Ertz-Herzogin zu Oesterreich von denen gesammten Nider-Oesterreichischen Ständen... abgeleget den 22 Novembris Anno 1740. Vienna: Johann Baptist Schilgen, [1742]. |

A table at the Bard Graduate Center laid with the St. Andrew's Service, a gift from Augustus III of Saxony to Elizabeth Petrovna Romanova, Empress of Russia 1741-1762.

Another exciting table I put together in 2011 at Hillwood Museum in Washington DC was designed to evoke a French dessert of the 1770s by using elements of the precious celestial blue service made at Sèvres for the Cardinal Louis de Rohan. At Hillwood we only had enough pieces of the service to construct a fairly modest table with a surtout dressed with chenille covered parterres. Rohan was famous for very large scale entertainments, especially when he was Louis XV's ambassador to Maria Theresa's court in Vienna. Our modest arrangement would have been dwarfed by Rohan's actual table settings, but again the aim was an evocation rather than an exact recreation. Rohan had a troubled relationship with Maria Theresa and her daughter Marie Antoinette. If you have heard about the remarkable 'affair of the diamond necklace' then you will know what I am talking about. If you don't, look it up, because it is an unbelievable story.

My table at Hillwood laid out with elements of Cardinal Rohan's Sèvres dessert service

All of the plates in Rohan's service are decorated with his monogram. You will notice that slightly to the right of the nearest place setting in the photograph above is an object ornamented with the same monogram. This was me having a bit of fun with history. The object is actually a sugar place name marker I made in the form of a rococo cartouche supported by gilded dolphins. In 2003 I made a number of these for an exhibition I curated at the Bowes Museum here in the UK called Royal Sugar Sculpture. I made them from two very important wooden sugar moulds which originally belonged to the office (confectionery kitchen) of the Princesse Lamballe de Savoie Carignan. The princess was a confidante and favourite of Marie Antoinette. The moulds, details of which are depicted below, are carved with motifs in the form of the ciphers of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. One that could also be used to make a small sugar basket.

Sugar place markers ornamented with the cipher of Marie Antoinette and the arms of the Princesse de Lamballe. In the foreground is a sugar basket and in the background one of Marie Antoinette's actual Sèvres dessert plates, kindly lent by Lord Rothschild. Lamballe, who tended to ape Marie Antoinette in matters of fashion, ordered an identical service from Sèvres for her own use.

These moulds were almost certainly carved to make sugar table ornaments for an entertainment in the Princess's palace in honour of the king and queen. Although they are tiny and fairly inconsequential, these stunning sugar objects tell us much more about the dining style of the ancien regime than the silly story about 'let them eat cake'. In fact, because they are authentic, they get us much closer to the excesses of Versailles court life than the grand slam displays of food in the recent movie Marie Antoinette, which though beautifully crafted were entirely wrong for the 1780s.

Sugar basket made from the confectioner's mould below

Motif for making the sugar basket and the ciphers of the king and queen of France- 1780s

The Princesse de Lamballe

Rococo sugar table marker ornamented with the arms of the Princesse

Carved motif on sugar mould to make the arms of the Princesse

Taking precious table objects out of the display case and arranging them with authentic period food in the manner for which they were designed can be a revelatory experience, but can only really be undertaken within a museum context. Period table settings in movies and television for instance, are in many cases spurious because the tableware - silver, porcelain, flatware etc is usually hired from prop companies and is rarely true to period. For instance, a few years ago I created the food and arranged a table for 100 guests for the Scorsese film The Young Victoria. The production designer organised the hire of the tableware, but what he provided me with on the set was a medley of late Victorian and early twentieth century middle class crockery, which was disappointingly inappropriate for a royal setting from the time of William IV.At the king's original birthday party held at Windsor Castle in 1836, which the film was attempting to recreate, the table was actually dressed with brother George IV's extraordinary silver-gilt Grand Service, which is still in the Royal Collection. Of course it is highly unlikely that a film company would be allowed access to a precious royal service like this. So as glamorous as our table may have appeared on the big screen, it would have faded into insignificance next to the real one, which all goes to show that it is rather difficult for Hollywood to do royal. Though loosely based on historical events, films like these are of course in reality fictional exercises. What is most important to the viewer is how well the stars perform their parts in the overall drama, not minutiae such as their knives and forks. So you might argue that it is a rather sad and obsessive of me to expect perfect historical accuracy in minor background details like table settings and food. However, a great deal of research often goes into other aspects of these productions, such as costume, hair styling, choreography of ballroom scenes etc., but only rarely does food and its service get truly expert attention.

Let me give you an example. One film which I really enjoyed for the extraordinary effort that was made in recreating the atmosphere of place and period was the movie version of Tracey Chevalier's historical novel Girl with a Pearl Earring. This was set in seventeenth century Delft, mainly in the home of the artist Johannes Vermeer. The almost miraculous lighting of the sets throughout the film was inspired by that mysterious soft diffused illumination for which the artist is celebrated. Art historians specialising in Vermeer must have been consulted because the rooms in the set were hung with paintings we know the artist actually owned. This attention to detail was tremendous and the film quite rightly won many awards for its remarkable cinematography.

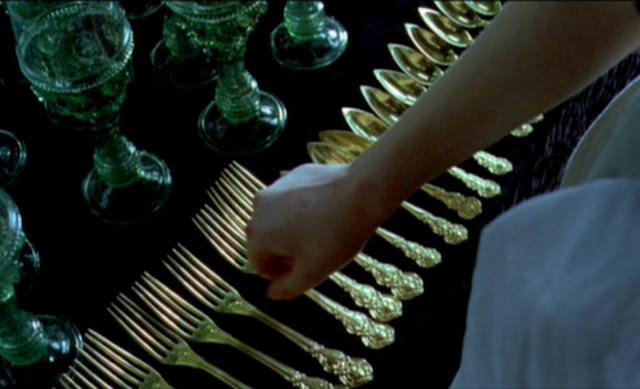

A still from Girl with a Pearl Earring showing the offending forks and spoons

However in the context of such a well researched film, one scene really disappointed me. This dealt with the preparation and service of food for a meal at which the artist entertains his patron. And I am afraid it was truly awful. There were many contemporaries of Vermeer who specialised in nothing but pictures of tables laden with food. As a result the Dutch table of this period is the most scrutinised in the history of art. Surprisingly this incredible wealth of evidence was entirely ignored by the filmmakers. At one point a servant cleans and lays out a ridiculous set of nineteenth century silver gilt forks and spoons. In 1665 most Dutch dinner guests turned up wearing their own cutlery at their belt or girdle. Sets like the one above of forks and spoons just did not exist. Because you carried it with you, your dining equipment was an expression of your status and each guest's was different. Some were extremely decorative and were probably used to show off, rather like the way that some people flaunt their mobile phones today. The kind of knives used by Vermeer's family and guests probably looked more like the Dutch seventeenth century examples below.

Left - knife and fork with ivory handles. The other two images are details of other ivory knife handles. All are Dutch and all were made during the lifetime of Vermeer. The example on the right depicts Bacchus.

I have chosen these particular Dutch eating implements in order to illustrate another detail in the film that irritated me. This was the manner in which the actors held and drank from their glasses. Look at the knife handles above and you will note that all of them depict somebody drinking. Note how they are holding their glasses - in every case by the foot. Dutch paintings of this period are also full of images of drinkers holding glasses in this way. Compare those I have reproduced below with the still from the film. The actor Tom Wilkinson is drinking from his glass in an entirely modern way. Imbibers all over Europe at this period held their glasses by the foot. Despite the wealth of evidence illustrating this mannerism, I have never seen a single actor in any period film or drama drinking in the correct style.

Tom Wilkinson drinking. A still from Girl with a Pearl Earring

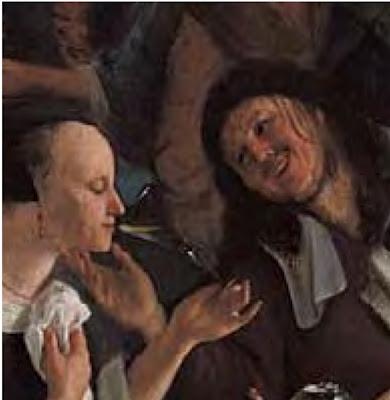

Note how this drinker in a painting by Frans Hals is holding his glass by the foot

Detail from a painting by Vermeer's Delft neighbour Peter de Hooch

Another detail from a painting by Vermeer's Delft neighbour Peter de Hooch

Woman drinking. Detail from a painting by Jan Steen

So if a number of Vermeer's contemporaries (not just painters, but also the cutlers of the day) clearly show us the correct way to hold a wine glass, what did he himself have to say on the matter? Well below are details from two of his paintings. I think they speak for themselves. The second one, The Girl with the Wine Glass is actually shown in the film and Tom Wilkinson explains that the lecherous male is the character he is playing. A pity that a little more attention wasn't paid to the lesson that could have been learnt from looking at the picture more carefully.

Johannes Vermeer. The Drinking Glass. (Detail). 1658-60.

Johannes Vermeer. A Girl Drinking. (Detail). 1659-60.

Attempting to recreate the food and dining culture of the past, whether in museums, film or television is fraught with problems. Authenticity for its own sake can be rather dry and pointless, but when it enhances the narrative and makes for better cinematography it can be wonderful. I would have loved to have seen Vermeer's guests showing off their fancy custom-made knives and quaffing their wine in the highly mannered style of the period.