Language provides us with many benefits. It makes it easier for us to teach each other skills and facts, allows us to share knowledge of who is to be trusted, form complex contracts and do all kinds of gossipy things. Given all of these advantages it’s proven rather difficult figuring out just why language evolved. Which of these benefits (if any) was the primary benefit that drove its evolution?

Robin Dunbar (of Dunbar’s number fame) is a big fan of the “gossip” explanation of language evolution. Dunbar’s also the man behind the social brain hypothesis, a popular and well supported explanation of why humans have such big brains. The gist of the social brain hypothesis is that living in large groups is advantageous but intellectually demanding. Thus the benefits of group life selected for bigger and better brains (Dunbar, 2003).

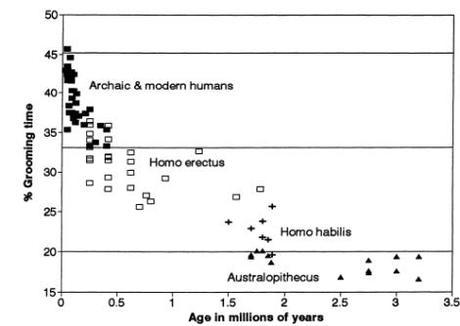

By using the correlation between brain size and group size theorised by the social brain hypothesis Dunbar is able to estimate the size of groups our ancestors lived in. These estimates indicate that by around 1.5 million years ago our ancestors were living in groups much larger than those of any modern ape. In fact, these groups are so large that maintaining all social relations with everyone through grooming (which is how apes stay friends) would’ve taken too much time. We needed to socialise in a new, more efficient way. This new and improved way of socialising was language (Aiello and Dunbar, 1993).

How much time we’d have to spend grooming if language didn’t evolve. 20% is the cut off time for what is plausible

As such, Dunbar believes the primary reason language developed was to build and maintain relationships. However, this conclusion is based on the inferences of the social brain hypothesis, which is in turn based on inferences from observations of group and brain size in living primates. Whilst making inferences isn’t necessarily a bad thing, supporting an idea with additional independent evidence can only increase it’s credibility.

So researchers from Oxford University (including Dunbar himself) have set out to look for such independent evidence. They hypothesised that if socialising was the primary reason language evolved we should be much better at socialising than say, conveying factual information or teaching someone how to hunt a mammoth.

To test this they gathered over 200 participants from around Oxford and got them to read 5 short paragraphs. 3 were different types of gossip, discussing sexual relations, who betrayed who and so on and 2 were instructions about how to gather honey without being stung. They hypothesised that if people were better at gossiping then they would be able to better remember details from the gossip stories, rather than the factual or deceitful ones.

The results confirmed this hypothesis, showing that people remembered nearly twice as many details about who was having sex with whom compared with how to gather honey from a hive without being stung. No particular detail of the gossip stuck out as being especially well remembered, people were generally good at remembering just about any of the social details.

The sole exception to this was women in sexual relationships, who seem to be a bit more receptive to stories about someone cheating on someone. Whilst you can no doubt conjure up some evolutionary psychology reason behind this, this test was not designed to investigate this which makes it difficult to arrive at any conclusions on the matter.

But can we conclude that gossip was the primary reason language evolved, as Dunbar and crew would like? Whilst this is certainly additional evidence for the gossip hypothesis I’d still say we’re very far from proving it. For starters there’s the fact that all the participants came from one part of the world (and most were white Europeans) making it difficult to extrapolate these results to the whole of humanity (Redhead and Dunbar, 2013). If this same effect can be demonstrated across the world in many different cultures then we may be onto something.

One day psychologists will realize University campuses do not represent the entirety of human diversity, but it is not today

There’s also the fact that the factual information isn’t particularly relevant to the day-to-day lives of the people involved. I doubt any of them, after reading the information thought “wehey, now I can go get some honey.” However, social relationships remain relevant to them, so they may be paying a bit more attention to stories about them. It would be interesting to see if the same effect was true if the factual information was a bit more relevant. Perhaps telling people at bus stops about upcoming changes to the bus schedule.

So whilst this research does lend some additional credibility to the gossip hypothesis, we’re still a long way from showing that was the primary reason language evolved. Although if that did turn out to be the case, it would explain the mysterious popularity of twitter. I just can’t seem to figure it out.

References

Aiello, L. C., & Dunbar, R. I. (1993). Neocortex size, group size, and the evolution of language. Current Anthropology, 34(2), 184-193.

Dunbar, R. 2003. The Social Brain: Mind, Language, and Society in Evolutionary Perspective. Annual Review of Anthropology, 32: 163-181.

Redhead, G., & Dunbar, R. I. (2013). The functions of language: An experimental study. Evolutionary psychology: an international journal of evolutionary approaches to psychology and behavior, 11(4), 845.