It’s another week, which means it’s time for another theory about how humans evolved such big brains. Last week a scientist argued inter-group conflict was responsible. Now an EvoAnthist from California is claiming that primate intelligence evolved to help us extract and process food1. Why all the different ideas? Are scientists baffled? Hardly. In the past few years it’s become increasingly apparent that there’s no single explanation for our big brains. Instead, a lot of factors were driving their evolution. Focused has now shifted towards trying to identify which of those factors was the most important.

Currently, it looks like sociality was the dominant evolutionary force responsible for our big brains. The social brain hypothesis posits that larger brains helped us have stronger relationships with more people. In turn, this allowed us to live in larger groups; which could search a wider area for food, better defend that territory against competition and so on2.

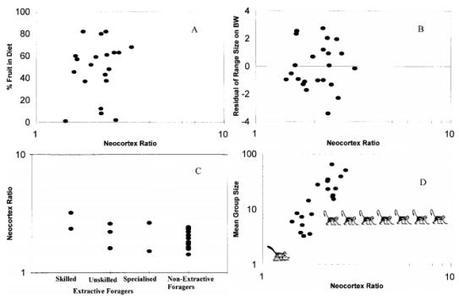

Now don’t worry. I’m not just trying to pad out this post with a discussion of other ideas. The social brain hypothesis is directly relevant to the new research. This is because of how it established itself as the “dominant” force in primate evolution. Dunbar – author of the social brain hypothesis – did this by comparing the correlation between brain size and group size in primates and noting how it was stronger than the link between brain size and other factors. For example, some had argued that large brains might have evolved to help primates remember when and where fruit ripened. However Dunbar showed that the link between amount of fruit consumed and brain size was weak; challenging this hypothesis2.

Dunbar’s comparison of brain size and many different factors. Bottom right is the correlation between group size and brain size, which is the strongest. Thus suggesting sociality was the most important factor examined. No, I have no idea why he put monkeys all over his favorite graph.

Now, the observant amongst you might have noticed the bottom left graph. This compares the complexity of the tools and techniques primates use to extract food from the environment (known as “extractive foraging”) with their brain size. Stuff like chimps using spears to extract meat from monkeys. Crucially, it notes that the correlation between the two is relatively weak; suggesting it was not an important factor in the evolution of primate brains.

This is what the latest research challenges.

It starts with a rather scathing critique of Dunbar’s work, arguing he used an overly simplistic model of extractive foraging. Whilst his contains three “levels” of it, other primatologists have developed a scale twice as large; containing many more sub-categories. This would be a much more representative view of how complex the extractive foraging techniques of these species are. The study also criticises the primate species Dunbar used in his study; noting that several that would score highly on that scale which were omitted. Like orang-utans1.

So you can probably see where this is going right? Having found a better metric for extractive foraging and a larger data set to examine; the research repeats Dunbar’s experiment and discovers there is a correlation between brain size and extractive foraging after all.

Haha, no. That would be too logical. Instead, after having poopooed Dunbar’s work the paper…kinda…just…ends…

My reaction when I realised what was missing from this paper

The closest it comes to making a positive link between brain size and extractive foraging is a reference to a paper from 2011. This other research tried to come up with a sort of “primate IQ” by looking at 7 or so “smart” things primates do that were correlated with other smart behaviours. The total set of these things was, in turn, correlated with brain size. Extractive foraging made the cut, but group size didn’t (although the study did note they found a link between brain size and group size anyway)3.

In other words, this research doesn’t make a particularly strong case that using complex tools and techniques to extract food from the environment was an important factor in the evolution of our big brains. Sure, it does a very good job of establishing that the extractive foraging hypothesis isn’t wrong. And that is kind of important. The idea has been sidelined since Dunbar’s criticism; maybe now it will be discovered to be important after all.

However, there’s a fairly big gap between “isn’t wrong” and “right.” This research fails to make that leap.

References (check out the dates, I’m bringing you research from the future!)

- Parker, S. T. (2015). Re-evaluating the extractive foraging hypothesis. New Ideas in Psychology, 37, 1-12.

- Dunbar, R. I. (1998). The social brain hypothesis. brain, 9(10), 178-190.

- Reader, S. M., Hager, Y., & Laland, K. N. (2011). The evolution of primate general and cultural intelligence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1567), 1017-1027.