Physically, modern humans aren't very impressive, lacking the sharp teeth, tough claws and all the other fun stuff that helps other animals survive in the wild. However, our body does have one thing going for it: endurance running. We can run surprisingly far for relatively little effort; even beating horses in extremely long distance races.

This unique ability has led some to argue that endurance running actually played a key role in human evolution; helping our ancestors capture prey by tiring them out. As such it was one of the key benefits that drove the development of bipedalism.

But does this idea have legs?

The evidence in favour

The key evidence that endurance running drove the evolution of bipedalism is how well adapted our bipedalism is for endurance running. It seems too finely tuned to be a coincidence.

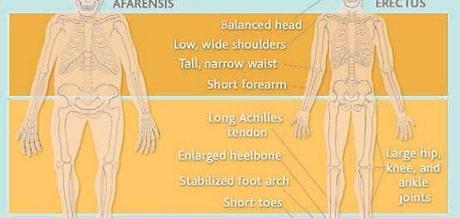

We have a long, elastic achilles tendon that "stores" energy from step to step, meaning less effort is required. Our short toes help push off the ground with ease and a large heel bone absorbs the impact as our foot comes back down. Even the very shape of our body seems adapted for endurance running, minimising how much each step makes us rotate so it's easier to keep our balance. The list of such adaptations goes on and on; and does seem quite compelling.

But perhaps what's even more compelling is just how unique this ability is. Very few animals have so many adaptations for endurance running. As such, if you made every mammal run a marathon, humans would actually come pretty close to first. Horses may be faster, but they have difficulty galloping for more than 15 minutes straight, and chimps can't really run further than 100 meters before getting tired out.

As a result of this, using endurance running to hunt (known as persistence hunting) does actually work. Continuously chasing after an animal and wearing it down until you can get close enough to kill it is a viable strategy, and utilised by some modern hunter-gatherer groups today.

So the case seems pretty settled, human bipedalism evolved for endurance running!

The evidence against

If you search research into whether endurance running drove human evolution, a couple of names will keep cropping up: Bramble and Lieberman, the original two to formulate this theory. Why don't more names appear? Because they haven't actually convinced that many people. So why do so many experts reject what seems like an overwhelming array of data?

Because most of it is circumstantial.

All of those physical adaptations "for" endurance running also help us do many other things; such as carrying objects long distances and endurance walking. So whose to say that they evolved specifically for endurance running? These physical features may help us run a marathon faster than most mammals, but they also mean we can carry stuff with 1/3 less effort than it took our ancestors. Which one was the real "reason" for their evolution?

Of course, this is also circumstantial evidence against the idea endurance running drove our legs' evolution. Sure, we can't say that it was the cause, but there's nothing there that says it wasn't. Is there any evidence that's more solid? Yes!

Imagine you're chasing after a herd of animals; doing a little bit of persistence hunting. Which animals are going to get tired out first? The ones in the prime of life, or the young, sick or old? The latter, obviously. Yet when we look at archaeological evidence of what our ancestors were doing, we almost always find a focus on prime adults. This is not consistent with what you'd expect to see from persistence hunting.

Conclusion

Humans are good at endurance running, there's no doubt about that. However, our legs are also well suited to walking long distances and carrying heavy objects. Teasing apart which was the key factor that drove the evolution of bipedalism is tricky. It might even be a nonsense question: multiple benefits may have been the cause. However, archaeological evidence shows that persistence hunting doesn't seem to have been that common; suggesting endurance running wasn't one of the primary benefits.

Or maybe we just didn't use it to hunt. Perhaps Homo erectus settled feuds with marathons.

References

Bunn, H. T., & Pickering, T. R. (2010). Bovid mortality profiles in paleoecological context falsify hypotheses of endurance running-hunting and passive scavenging by early Pleistocene hominins. Quaternary Research, 74(3), 395-404.

Crompton, R. H., Vereecke, E. E., & Thorpe, S. K. S. (2008). Locomotion and posture from the common hominoid ancestor to fully modern hominins, with special reference to the last common panin/hominin ancestor. Journal of Anatomy, 212(4), 501-543.

Liebenberg, L. (2006). Persistence hunting by modern hunter-gatherers. Current Anthropology, 47(6), 1017-1026.

Lieberman, D. E., & Bramble, D. M. (2007). The Evolution of Marathon Running. Sports medicine, 37(4-5), 288-290.