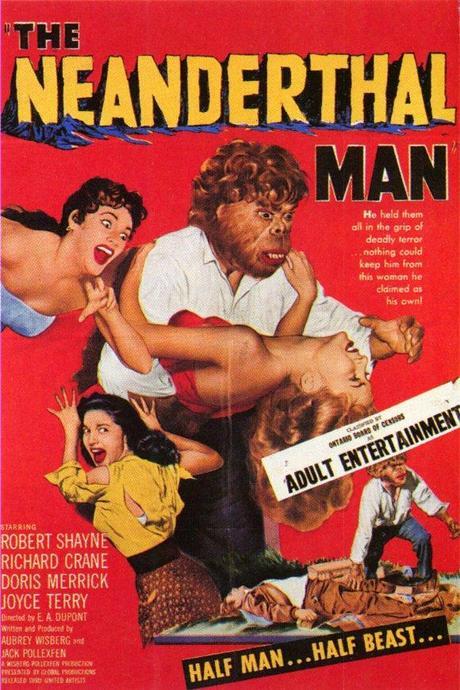

The image of Neanderthals needed a lot of rehabilitating

Victorian scientists originally thought our close cousins, the Neanderthals, were little more than dumb brutes; an image which has seeped into popular culture and still persists to this day. Subsequent discoveries have helped rehabilitate the Neanderthals’ image, revealing that had a brain bigger than our own! They were capable hunters, excellent tool makers and even buried their dead. However, whilst it’s clear Neanderthals were more advanced than the Victorians thought there were still many differences between us.

Is language one of them?

Figuring out when language evolved is really difficult given that most of the body parts responsible for speech decay. The palaeoanthropological record contains exactly zero tongues, brains and vocal cords, forcing us to look for other evidence of language. The clearest evidence of modern speech is the creation of symbolic artefacts, such as the famous cave paintings1. However, the earliest unambiguous evidence of symbolism was made by modern humans and dates to ~77,000 years ago2, around 300 – 500 thousand years after we split from Neanderthals3. Does this mean they lacked that symbolic capacity and so didn’t have language?

Many researchers believe they actually did, pointing to Neanderthals’ anatomy as evidence. Although most of the stuff connected to speech does decay, a few choice pieces remain. The Neanderthal hyoid bone (which anchors many tongue and mouth muscles used in speech) falls within the range of human variation1. Their spine also supports the case for language, revealing they had the muscles needed for fine breathing control, a must for any attempt to talk4.

A Neanderthal skull and hyoid bone (shown beneath the skull)

But just because they could make noises like a human doesn’t mean they could talk like us. Language is a complex thing, requiring a whole host of cognitive abilities such as semantics, syntax and all sorts of other fancy words (no pun intended). None of these will be preserved in a fossil. Fortunately we have more than just bones to look at and many scientists are has turning to the Neanderthal genome; examining whether our extinct cousins have any of the genes linked to language.

It turns out that Neanderthals have the human version of FOXP2; a critical gene that helps us control the complex muscle movements in our lips and lungs (amongst other things) needed to talk. Humans born with a damaged version of the gene have difficulty speaking as a result5. The gene may also be linked to language comprehension and processing since many people who have the damaged variant also have difficult creating and organising long sentences, often mixing up word order.

The presence of FOXP2 in the Neanderthal genome has been widely touted as strong evidence they were capable of speech. For example, the National Geographic story on the discovery of FOXP2 in Neanderthals is “Neanderthals had same “language gene” as humans.” Although appropriately cautious, using words like “suggests” and “challenges”, the article does include the quote “From the point of this gene, there is no reason to think that Neandertals did not have language as we do“

However, FOXP2 isn’t the only gene linked to language. CNTNAP2 is linked to language development in children, whilst ASPM and MHC1 are associated with being able to pick out different tones. And these 3 other genes are absent from Neanderthals6! On balance it would seem that the genetic evidence does not support the idea that Neanderthals had fully modern linguistic capability.

Nonetheless, the anatomical evidence is hard to ignore. Particularly given that some of it would actually hinder a Neanderthals’ chance of survival. The larynx is a valve in the throat that prevents food from getting into the lungs but in human and Neanderthals it has shifted position4, improving the range of sounds but increasing our risk of choking to death. Evolution would not select for these features unless Neanderthals were doing something beneficial with them.

Some researchers have attempted to reconcile this fact with the genetic evidence by suggesting Neanderthals had a sort of “proto-language.” This language would’ve it was more complex than anything modern primates are capable of. Their anatomy and FOXP2 suggests it would’ve involved a diverse range of sounds; perhaps on par with humans. However, it would likely not have possessed all the key characteristics of human language; such as a flexible syntax that allows us to create new sentences as we go. Like that one.

Neanderthals are so similar to us that our ancestors interbred with them, yet they’re still unlike anything we see today, most likely lacking our capacity for language. I guess that goes to show just how randy ancient Homo sapiens was.

References

- d’Errico, F., Henshilwood, C., Lawson, G., Vanhaeren, M., Tillier, A. M., Soressi, M., … & Julien, M. (2003). Archaeological evidence for the emergence of language, symbolism, and music–an alternative multidisciplinary perspective.Journal of World Prehistory, 17(1), 1-70.

- Henshilwood, C. S., d’Errico, F., & Watts, I. (2009). Engraved ochres from the middle stone Age levels at blombos cave, south Africa. Journal of Human Evolution, 57(1), 27-47.

- Boyd, R., & Silk, J. B. (2009). How Humans Evolved. WW Norton & Company, New York.

- Dediu, D., & Levinson, S. C. (2013). On the antiquity of language: the reinterpretation of Neandertal linguistic capacities and its consequences.Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 397.

- Lai CSL, Fisher SE, Hurst JA, Vargha-Khadem F, Monaco AP (2001). “A forkhead-domain gene is mutated in a severe speech and language disorder”. Nature 413 (6855): 519–23.

- Berwick, R. C., Hauser, M. D., & Tattersall, I. (2013). Neanderthal language? Just-so stories take center stage. Frontiers in psychology, 4.