I have never deceived anybody for I have never belonged to anybody. My independence was all my fortune, and I have known no other happiness; and it is still what attaches me to life. - Cora Pearl

The details of her birth are a litany of “probablies”; she was probably born in Plymouth, England on February 23rd, 1835, but that may be the date of her christening and she later claimed the year to be 1842. Her birth name is usually given as Emma Elizabeth Crouch, but her death certificate calls her “Eliza Emma” instead. Her father was a cellist named Frederick Nicholls Crouch who was the composer of “Kathleen Mavourneen”, a song which was extremely popular in the United States during the Civil War period. Unfortunately, Crouch was a “one-hit wonder”, but never learned to live within his means; he fled his creditors in 1847, abandoning his wife and six daughters and moving to America (where he is known to have remarried several times before dying in 1896). Lydia Crouch was an attractive woman and soon found a live-in boyfriend who was willing to support her children, but Emma did not get along with him and so was sent to a boarding school in Boulogne, France to be educated by nuns. After eight years (and numerous lesbian relationships mentioned in her memoirs) she returned to England in 1855, moved in with her maternal grandmother and went to work for a milliner in London.

Emma chafed under the strictures imposed upon middle-class Victorian girls and one day she ditched her chaperone, accepted a man’s invitation to have cake with him, and drank a bit too much gin…with predictable consequences. In the morning she found he had left her a five-pound note (about £250 today), and though she later claimed to have been “horrified” by the experience, the truth is that she used the money to rent a room for herself and immediately began hooking. It wasn’t long before she started working at a brothel called The Argyll Rooms, whose owner Robert Bignell soon recognized her potential and asked her to be his mistress, moving her into a suite of her own. Within a year he took her on holiday to Paris, and she so fell in love with the city that she decided to remain; she adopted the stage name “Cora Pearl”, took a cheap room, and made her living as a streetwalker until she met a pimp named Roubisse who set her up in better quarters. He paved the way for her future success by teaching her the business and insisting she develop her professional skills, and by the time he died of a heart attack in 1860 Cora was already well-established with Victor Masséna, Duc du Rivoli (later Prince of Essling).

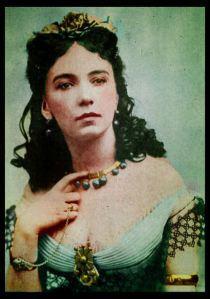

In 1865 she became the mistress of Prince Napoleon, the Emperor’s important and fabulously wealthy cousin. He supported her for nine years, usually for about 10,000 francs per month, and also bought her many expensive gifts and several houses (including a small palace, les Petites Tuileries). And though he frowned on her seeing other clients, she secretly did so anyway and charged them that much more for the risk. It isn’t that the Prince didn’t give her enough; it’s just that she was incredibly extravagant and regularly sent money to both her mother and father. She became a very popular celebrity and was well known for wearing heavy makeup and dying her hair outlandish colors to match her wardrobe. In 1867 (the same year a cocktail was named for her) she took the role of Cupid in Offenbach’s operetta Orpheus in the Underworld, dressed in a costume which consisted of little more than a diamond-studded bikini; she only appeared twelve times, but the jewels brought 50,000 francs at auction.

Cora’s downfall began with the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, during which she allowed her homes to be used as hospitals and paid for doctors and medical supplies for wounded soldiers out of her own purse. But the disastrous defeat of the French meant the end of the Empire; Prince Napoleon fled to England along with the Imperial family, and though Cora went with him the Grosvenor Hotel refused to let her stay for fear of scandal (ironically, the hotel’s modern management has capitalized on the incident by unveiling a “Cora Pearl Suite” last year). Within a few months she returned to Paris, but the postwar mood was no longer conducive to the social climate in which a courtesan thrives; so, when the wealthy young Alexandre Duval became obsessed with her, she did not discourage him despite the fact that she despised jealousy in her patrons. In less than a year he had spent literally his entire fortune on her, and when his family refused to give him any more she refused to see him any longer. On December 19, 1872, he went to her house with murderous intent, but the gun accidentally discharged while he was trying to force his way past her servants, shooting him in the side.

After her death she passed into obscurity, and would barely be remembered today if not for a curious epilogue which occurred almost a full century after her death. Apparently, Cora wrote an earlier version of her memoirs during her slow decline in the ‘70s, containing real names and many juicy details; it was released by a British publisher in 1890. The few who knew about it assumed it to be an English translation of her bland 1886 memoir, but when a modern collector named William Blatchford got ahold of a copy he realized that this was not the case. Blatchford publishing the find in 1983 under the title Grand Horizontal, The Erotic Memoirs of a Passionate Lady, and its vivid, on-the-spot descriptions of the gay life during the Second French Empire rekindled interest in its author and has given her, albeit posthumously, another chance at the fame she so enjoyed in life.