by Paul J. Pelkonen

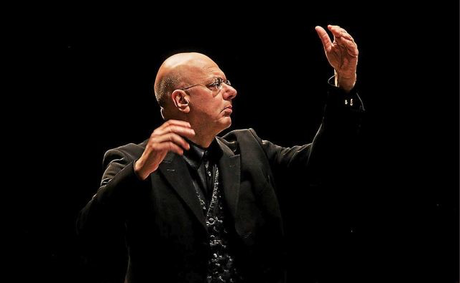

Leon Botstein. Photo by Kallaher for Bard College.

It is never a good idea to follow in the footsteps of Richard Wagner. That truism could easily be applied to Edward Elgar's long-neglected oratorio The Apostles. Elgar conceived The Apostles as the first part of a planned trilogy of stage works based on the New Testament, following a visit to Bayreuth in 1902. However, this piece, played at Carnegie Hall on Friday night by Leon Botstein and the American Symphony Orchestra, is problematic at best.Elgar is best remembered for his two symphonies, the Enigma Variations and The Dream of Gerontius. The Apostles was his follow-up, written in 1903 and designed for amateur choruses and orchestras to engage in group performance, thus mulling on the story of Jesus. (Elgar was a staunch Catholic.) It was planned as the first of a trilogy of works based on the teachings of Jesus. This performance marks the first New York mounting of the work at Carnegie Hall since it premiered there in 1910.

The Apostles retells the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ through the eyes of Peter, Mary Magdalene and Judas. Elgar uses thick] orchestration throughout the work, with all the weight of Edwardian furniture. It has some of the solemn majesty of Parsifal without that work's innovation, a trap that also sunk post-Wagnerian efforts by composers like Leoncavallo and Pfitzner. Indeed, it is that composer's Palestrina that this oratorio anticipates, albeit with less interesting harmonic writing.

A stirring orchestral introduction laid out the leitmotivic material. The first half was three scenes, climaxing in Jesus walking on the Sea of Galilee, expressed in a solemn tread of brass and percussion and some impressive writing for chorus. However, these early pages seemed to flummox the men and women of the Bard Festival Chorale: they sounded under-rehearsed and blurry around the edges. This had the effect of reducing the beautiful text of this work. Syllables and phrases ran into each other, creating a wall of sound that was pretty to listen to but at times unintelligible.

Some strong soloists eased the passage of this work. Among them, Sara Murphy, bright-toned as Mary Magdalene and the always reliable soprano Jennifer Check. Alfred Walker was the best of the men here, giving Judas an extra dimension of fallability with his big, tragic bass-baritone, rich in color and tone. Tenor Paul McNamara seemed overparted as St. John, who served much as the Evangelist does in the St. Matthew Passion. Bass-baritone Joseph Beutel was strong as St. Peter. However, as Jesus, baritone Adrian Rosas seemed out of his depth, his voice as one crying in a wilderness of orchestration.

Dr. Botstein's leaden conducting didn't help. As the work built in slow momentum, he goaded the brass and percussion into a plodding march, building momentum before letting the beat vanish into a swirling mist of woodwinds and strings. Orchestral effects abound: the clang of triangle and glockenspiel for Judas' thirty pieces of silver and an offstage shofar (ram's horn) whose bleat is startling at best. But as Elgar is no Richard Wagner, he is also no Richard Strauss.

The second half was an improvement, anchored by a moving treatment of Judas. Here, Elgar contrasts Judas' guilt and suicide with the judgment of Jesus, creating the sound of a man in spiritual crisis against the horrible reality of his actions. Ms. Check and Ms. Murphy came to the fore in the crucifixion and the scene at the tomb which followed. The last scene was a peculiar serving of Elgar's boiled beef and vegetables. It needed a firmer beat and stronger hand than Dr. Botstein's, with the final, celestial chorus being less than overwhelming.