by Paul J. Pelkonen

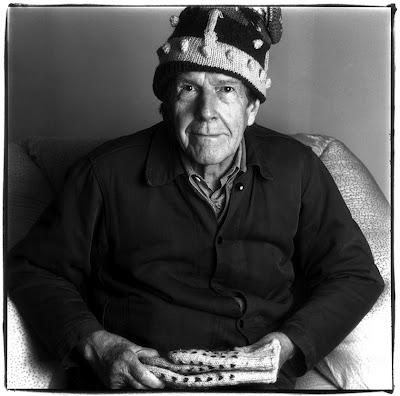

John Cage in 1986. Photo by Andreas Pohlmann © the photographer.

Too often, the life of a classical music critic involves the same procedure over and over. We sit in preselected seats, usually in the same section of an opera house or concert hall. The musician(s) are onstage directing sound toward us. And we don't get up except for a quick break for intermission, a gulp of coffee, a friendly chat with a colleague, or a trip to the loo.The Tuesday night premiere of Kevin James' 100 Waltzes for John Cage broke all of those rules. The 75-minute piece for nine players (Mr. James' group, the [kāj] ensemble) and pre-recorded sounds (played through quadraphonic speakers) proved an active listening experience. Audience members and press alike were invited to walk through and around the performance, experiencing the landscapes of sound from multiple angles.

Mr. James drew inspiration for 100 Waltzes on Cage's own 49 Waltzes for the Five Boroughs, a legendary 1977 work that used a map of New York and calculations from the I Ching to provide players with 147 addresses at which to play, but no indication what they were to do once they got to the randomly chosen location. This new work used random number generation (his assistant was introduced as his "tosser of coins") to pick locations at which to "mine" sounds and preserve them.

The work's second element consists of previously chosen musical fragments of different composition, electronically "beamed" to iPads transported around the concert hall by the musicians. The fragments are also picked indeterminately, and include everything from Viennese waltzes for clarinet and flute to burlesque bump-n'-grind drumbeats. The waltzes also incorporates repeated variations and expansions on triple-time rhythm. They were played by Mr. James' group, an octet with one vocalist.

The musical experience provided by 100 Waltzes was jarring at first, yet proved rewarding as the work unwound and the composer's intentions materialized from aural chaos. Waltz fragments coiled, wound and occasionally clashed with the ambient pre-recorded noises: helicopters lifting off and landing, a truck's air brakes or the sounds of birds in New York public parks.

Singer Daisy Press used the melodica to generate tones to sing, and alternated between words, catlike mews and wordless melismas. At any given time, a player would stop, lift their iPad and cross the room to a new music stand to create a fresh combination or ensemble, occasionally leaving their colleagues to solo against the noise of the city's ambient sound.

In choosing to move or stay still, the small, rapt audience was invited to participate in the performance in some small degree, warming themselves by the fires of inspiration and occasionally dodging to avoid the rush of an oncoming truck. The musicians played with standard technique, although trumpeter Herb Robertson used part of a mute to produces strange breathy noises from his horn and later ended the piece by rhythmically screwing and unscrewing his mute from the trumpet's bell.

The [kāj] Ensemble offers two more performances of this composition at the DiMenna Center this week. Thanks to the indeterminate methods chosen by Mr. James and inspired by John Cage, each dance of 100 Waltzes will be completely different.