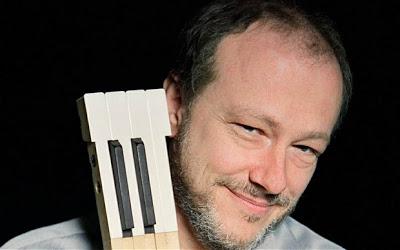

Marc-André Hamelin grabs a slice of the piano.

Photo © Marc-André Hamelin courtesy Hemsing Associates.

Mr. Hamelin started simply, with a clear and lovely reading of the Mozart C Major Sonata. He lengthened to the opening phrase, almost a polite hesitation in the expression of this famous theme. He played this familiar work with confidence and ease, sounding most at home in the skipping final movement with its light ornamentation. It was lovely stuff, if a little dry.

With the next work, his design became clear. This four-minute Gigue, Bolero and Variations on a theme by Mozart came from the pen of Ferrucio Busoni, a German composer whose keyboard works are known for their strict requirements, idiosyncratic harmonies and knotty classicism. Mr. Hamelin played this short piece with real fire and enthusiasm. His great strength as an artist has always been utter fearlessness in the face of little known and challenging repertory.

Mr. Hamelin ended the first half of the evening with a thrilling Gaspard a la Nuit, that trio of pianistic nightmares from the pen of Maurice Ravel. He made Ondine, the flowing opening movement sound easy, with an impossibly smooth legato between notes as his pianos pun the tale of Ravel’s water-sprite. The central movement had eerie hollow notes in its portrait of a hangman’s gibbet, with ghostly chords ornamenting the slow tread of the thematic line.

Then it was time for Scarbo, the final movement and the big are of many an aspiring conservatory student. Again the taut rhythms and keyboard leaps were met with acrobatic ease, with the theme emerging from the grumbling so far the extreme low register of the instrument. For Mr. Hamelin, the angular nature of the writing becoming not just a finger busting exercise but a vehicle for real emotional expression.

Th second half of the evening opened with the first New York performance of Mr. Hamelin’s own Pavane Variée. This is a set of variations on “Belle qui tunes am vie” a 16th century French theme attributed to the composer Thionot Arbeau. In this set of movements, Mr. Hamelin mined the depths of this somber tune, with the slow theme bring restated as bright dances and brilliant song-like utterances. The variations built upon themselves with elaborate themes emerging in blossoms of baroque ornamentation.

For his grand finale, Mr. Hamelin chose the Liszt Sonata in B minor, a single half-hour movement that forces the soloist to become his own orchestra. With its hazy, dream-like minor chords and descending themes for the left hand, this work embodies the “music of the future" espoused by Liszt and his famous son-in-law Richard Wagner. Hints of flying horses and clinched lovers abounded, with Mr. Hamelin providing a vast palette of colors in the shifting chords and heroic main theme. For all its bluster, the work ends in a romantic dream, with the soft chords dissolving into nothingness as the harmonies finally resolved.

Mr. Hamelin obliged the applause of the audience with a trio of encores. The first of these was a Liszt transcription of the Chopin song “My Darling," showing the sometimes awkward meeting of minds between these two friends and rivals: the one reserved and the other flamboyant. Another transcription was next: the Gershwin tune Liza, expanded upon and invented on to dazzling effect by the late American composer pianist Earl Wild. Finally, Mr. Hamelin left the audience with a dose of difficult impressionism; the “Feux d’artifice” from the second book of Debussy’s Preludes.