Herbert Blomstedt conducts the New York Philharmonic.

by Paul Pelkonen

(Ed. Note: Superconductor reviews usually appear within 24 hours of attending a concert. Since I came down sick on Saturday afternoon, it's running now. Thanks for your patience.--P)

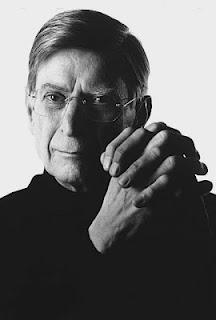

Conductor Herbert Blomstedt.

Photo by R. J. Muni.

The New York Philharmonic welcomed Swedish conductor Herbert Blomstedt back to the podium of Avery Fisher Hall last week for a stellar program of Mozart and Tchaikovsky.

A longtime presence at the San Francisco Symphony (where he served as music director for a decade), Mr. Blomstedt was born in the U.S. but grew up in Sweden. Now 85, his distinguished podium style features elegant, arching lyric lines and a brisk, business-like approach to making music.

The concert opened with Mozart's Jeunehomme Concerto, led with a fine balance by soloist Garrick Ohlsson. Mr. Ohlsson, who looks more like a retired NFL tight end than an international concert pianist, played this music with a light touch that belied his big frame.

Through the three movements, Mr. Ohlsson's big hands moved agilely, drawing out the playful aspects of the 21-year old Mozart's writing as well as the serious harmonic ideas that the composer would explore in operas like Idomeneo. Whether drawing sweet phrases in the slow movement or dazzling listeners with technical runs and arpeggiated figures in the finale, Mr. Ohlsson made the whole concerto look deceptively easy.

The Tchaikovsky Fifth stands at the center of the composer's late tryptich--a fate-driven work that draws inspiration from Beethoven as well as the composer's own lyric Russian style. It is also the most determinedly optimistic of these last three symphonies, standing between the tragic Fourth and the suicide note of the Pathetique.

Happily, this symphony is perfectly suited to the New York Philharmonic's strengths, a big, tempestuous work grounded around a motto theme. Sturdy brass playing--another specialty of this orchestra--is required. To all this, Mr. Blomstedt contributed propulsion, making the powerful motto theme dance where other conductors simply power ahead.

Mr. Blomstedt's leadership, expressive and vigorous without the benefit of a score, underlined the crucial relationship between the four movements of this symphony. In the Adagio, with its lonely horn-call that leads up to a huge climax, and in the courtly, almost rococo dance movement, the conductor underlined reappearance of the "motto" theme, showing the audience the coherent structure that Tchaikovsky was trying to achieve.

The conductor took an energetic approach to the finale, driving that famous march rhythm forward with a relentless, propulsive drive. Mr. Blomstedt also took the brief pause right before the coda very quickly. Some conductors pause too long, and an uninformed audience applauds too early. This performance brooked no such interruptions, ending in a powerful blaze of sound.