Week Two of The Modern Beethoven at the New York Philharmonic.

by Paul Pelkonen.

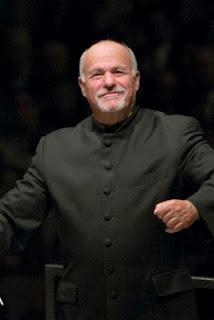

David Zinman.

Photo by Priska Ketterer.

The Modern Beethoven is conductor David Zinman's three-week essay arguing the influence of Ludwig van Beethoven on 20th century composition. Thursday night's concert at the New York Philharmonic kicked off the second week of the festival. The program featured Samuel Barber's 1946 Cello Concerto, bracketed by the Eighth and Fourth Symphonies.

Although all nine Beethoven symphonies are the bread and butter of orchestral programming, the Eighth is infrequently heard. It is a seeming throwback to the composer's early style and the galant 18th century writing of Haydn and C.P.E. Bach. This is a work shot through with Beethoven's unique sense of musical humor, full of inside jokes, self-references and riddles for a skilled conductor to solve.

The first of these problems: the unique opening phrase of the first movement. It seems to start in the middle of a theme, almost as if the listener walks in just as the punch-line of a joke is being told. The resulting peal of orchestral laughter (that actually starts the symphony) was slightly muffed last night, though the Philharmonic players pulled things together to deliver a crisp reading.

The second movement owes its debt to the invention of the metronome. Steady ticking rhythms are plucked out and the sprightly main theme burbled over the meter. The final two movements were even better, Beethoven at his most cheerful interpreted by Mr. Zinman's seemingly casual, but fiercely accurate conducting.

For the "modern" portion of the program, cellist Alisa Weilerstein joined the expanded orchestra to play Samuel Barber's Cello Concerto. Ms. Weilerstein has established herself as a star on her instrument in the last decade. Here, she played Barber's thorny opening with a fierce attack, her left hand racing up the neck of her instrument as she bowed with intent and concentration.

The slow movement breathed with a mourning air, possibly reflecting the work's post-World War Two origins. The final movement featured kinetic, breath-taking playing from Ms. Weilerstein. Her left hand leapt, spider-like from interval to interval. Mr. Zinman provided jazzy accompaniment, the music seeming to presage the film scores of the decades that followed the work's premiere.

The concert ended with another merry Beethoven symphony: the Fourth. This is a much simpler joke than the Eighth, with a slow introduction that leaps into a Haydn-like allegro without any warning. The four movements were played with clean, precise lines, with Mr. Zinman looking like he was having a marvelous time bringing this warm, good-hearted music before the ears of the public.