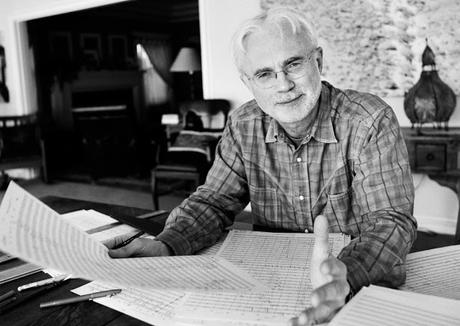

The composer John Adams. Photo by Margaretta Mitchell.

John Adams is no longer the nervy young composer who rode a minimalist wave to popularity with operas like Nixon in China. He is 70 now, and his belated birthday celebration was the subject of this week's set of all-Adams concerts at the New York Philharmonic under Alan Gilbert. He was at Friday's matinee concert, a known quantity warmly greeted by an audience that is often hostile to any music written after 1910.Friday's matinee performance introduced not only Mr. Adams, who gave a short talk to the audience before the performance began, but the New York Philharmonic String Quartet, which made its debut with this run of performances. The NYPSQ is Frank Huang and Sheryl Staples (the concertmaster and first chair from the violin section) first violist Cynthia Phelps, and Carter Brey, leader of the cellos.

They participated in Mr. Adams' pre-concert demonstration, playing short excerpts from the late Beethoven String Quartets to show how those musical ideas fit into Absolute Jest, the 2012 concerto for string quartet and orchestra that made up the first half of the program. It was indeed lovely to hear these four fine soloists essay parts of these monumental Beethoven works, and one hopes that this new collaborative direction will be a long and fruitful one.

Absolute Jest has been covered elsewhere in this publication and it remains much as it was, a sort of remix of various Beethoven ideas (the pounding timpani from the Scherzo of the Ninth, themes from the other late symphonies and ideas from the aforementioned string quartets, remixed and rewoven into a large, heavy orchestral tapestry with the Adams minimalist technique (small thematic cells, endless repetitions) as the guiding ideal.

Beethoven was the original and superb minimalist. Mr. Adams' creation (this is a form he has used before as his Shaker Loops is built from theme fragments in another string quartet) is logical enough extension of the original, and in some ways is reminiscent of the late 19th century "Back-to-Bach" excursions of Max Reger. There is little in the way of wit and imagination. Mr. Gilbert and his players showed that while Absolute Jest is well-crafted and initially entertaining, its mixture of compositional rigor and sardonic wit did not sustain well for its length.

Harmonielehre (the title means "Study of Harmony" and is a nod to Schoenberg) is a much larger composition, debuting in 1987. However, this is a much bolder and more interesting work, a set of three tone poems that were inspired by the composer's dreams and his study of Carl Jung. The untitled first movement was a long, mesmerizing arch, weighted with enormous, fast crescendoes at each end supporting a graceful span of slowed notes, which with Mr. Adams' technique felt like a literal slowing and reversing of time and space. It was gloriously and lovingly played.

The second movement, The Anfortas (sic) Wound is a sort of reflection of the suffering of the Grail King in Wagner's final opera, It is unclear whether the trumpets, wandering through the orchestral mist represent the long-suffering monarch or Parsifal himself, blundering about in his efforts to return home to Montsalvat with the spear that dealt the wound and can bring healing. Only Mr. Adams knows, but this inscrutable moment was an absorbing listen, building to an agonizing fortissimo climax.

It yielded to the wonderfully titled Meister Eckhart and Quack, referencing both the medieval mystic whose writings may have sparked Martin Luther to enact the Reformation and Adams' own daughter, who had the latter as her childhood nickname. This was music of unfettered joy, with the bright tones and ecstasy of Mahler's Das himmlische leben and none of that song's death-imagery to spoil the mood. As played by Mr. Gilbert and his forces, this was Mr. Adams at his most ecstatic and inspired, music of unfettered joy expressed in the minimalist manner.