by Paul J. Pelkonen

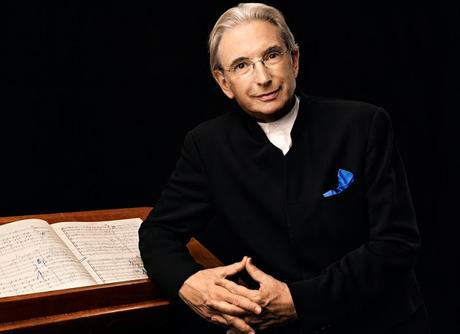

Michael Tilson Thomas elbows a score. Photo by Art Streiber.

The classical music world is a place where absolute power can rest in the hands (or the pen) of a single individual. On Thursday night at Zankel Hall, Michael Tilson Thomas (who is one of those individuals who is allowed such a privilege) was allowed an exercise in that kind of power. The composer, conductor and educator hosted this concert featuring pianist Yuja Wang and members of his Miami-based training orchestra the New World Symphony. He led the orchestral performances in its first and second half. And he wrote a good deal of the music performed.The concert opened with Mr. Thomas (or, as he styles himself "MTT") introducing two of his works for solo piano, both to be played by Ms. Wang. The first, Sunset Soliloquy was penned in his parents' house when he was just 19 years old. It began as an exercise for the left hand, playing dreamy intervals that rotated and repeated like shifting, lengthening shadows. The right then played dazzling figurations and sharp, angular notes. Finally, Ms. Wang's hands combined forces to paint one impressionistic picture in different colors of sound.

With barely a pause, Ms. Wang launched into the second piece. This was her second performance this week of You Come Here Often?, and that piece's official New York premiere. This is a jittering, energetic piano workout designed as a showpiece encore. The work, inspired by Mr. Thomas' time spent living in New York in the decadent late '70s is a first person piano narrative of the club experience, from hearing the tumult from outside on the street to being in the center vortex of it and attempting a romantic liaison amongst flashing lights and chattering chaos. Dating is never easy, but Ms. Wang made this stunning piece look simple.

The piano's lid was removed and it was rolled to the back corner of the stage to set up the next piece. This was Mr. Thomas' Four Preludes on Playthings of the Wind, a work written for soprano soloist, a pair of backup singers and two bands, playing in opposition to each other and only occasional musical concordance. Mr. Thomas set these poems by Carl Sandburg in a manner that might make one recall Charles Ives. In one corner: a chamber orchestra enhanced with some modern percussion instruments like vibraphone and lions' roar. In the other, a rock and jazz band lined up against the back wall of the stage: two electric guitars, bass, drums and a line of brass and sax players.

This attempt by Mr. Thomas to evoke the Chicago poetry of Sandburg swam boldly into the muddied waters of the third stream, that vague concordance between rock, jazz fusion and classical. In doing so, these efforts sank quickly to the bottom and stayed mired in the musical silt. Sandburg's cavalcade of ugly urban images evoked misery, decay, crumbling and a textual obsession with the triumph of rats over humanity. Not Mr. Thomas' bold podium efforts nor the technically excellent poly-stylistic vocals of soprano Measha Brueggergosman could save these verses from the muck.

The soprano entered in a monkish cloak, her two backup singers (Kara Dugan and Krista Toedtman) flanking her. And then they shucked off revealing gold sequined dresses, vamping like a Supremes tribute. The chamber ensemble made pleasant enough noises, reminding one of Mr. Thomas' mentor Leonard Bernstein in their use of quirky musical phrases and bold West Side Story rhythms. However, they suffered from ensemble interruptus thanks to the erstwhile rock band. This second group kept changing musical styles from rockabilly to funk to punk that sounded more like prog, suffering from the same issues that emerge when an academic tries to use technique to reconstitute these genres that lie outside their expertise.

Happily there were no such problems with the final work on the program: Mr. Thomas' edited edition of the Gustav Mahler orchestration of Schubert's String Quartet No. 14 in D minor, the one known as "Death and the Maiden" after that composer's song of the same title. (Whew, that was a lot of credits.) This expansion of this quartet divides the labor of four players into five musical groups, with the double basses only coming in to add oomph to key forte moments in the score. The spidery loneliness of Schubert's music is replaced with great rolling waves of orchestration, but thanks to Mahler's skill as an orchestrator (and Mr. Thomas' editing and taut leadership) this performance proved that Mahlerized Schubert is a curious enhancement that does nothing to detract from the original masterpiece.

If you enjoyed this article, it's time to click over to Superconductor's Patreon page, and help support the cost of independent music journalism in New York City at the low cost of just $5/month.