When I think of Christmas, I think of my grandmother’s house – a two-story in the city, crowded and loud, its kitchen filled with ten more people than reasonably fit inside, with wooden and metal folding chairs placed all around (and beyond) the table.

When a guest arrived, four people had to relinquish their seats to clear the door. That cold blast of air brought love in from the outside – neighbors with cookies, friends of my grandfather, or the Avon lady. The scent of their leather coats hung in the chilly air.

The floor was linoleum, probably, and the metal chairs scraped, just as you’d imagine.

Poster-board decorations, dog-eared from years of use, some with faded velvety finishes, hung on the walls. Electric candles that bubbled water sat in each drafty window.

The light was harsh. The stove sat alone on a wall, and the big steel doors of the ‘icebox’ swung open and closed, attempting to satisfy the hungry crowd. Laughter crested and fell between the clanking of plates and glasses. Some would share chairs or sit on laps to secure what little room they could find. Others just stood and ate.

After dinner, my grandmother would make it a point to seat the kids in the middle of the floor, making everyone ‘ooh’ and ‘aah’ at each present we opened, to the point that it became a joke.

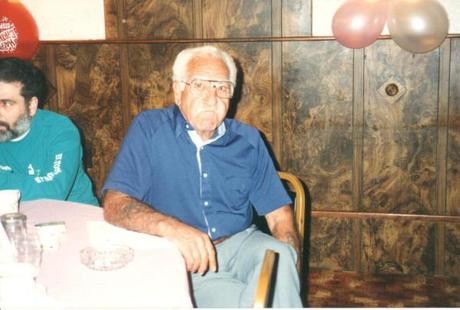

My grandfather would retire to his recliner and turn on the TV -probably a football game – or play music. I’d sit with him, usually, no matter what he’d watch. He’d hand me those Columbia House stamps, the ones you’d used to choose your “10 Free Albums”, and a piece of cardboard on which to stick them. Every so often, he’d get me seven or eight cassettes of my own, which I carried around in a case as if it were filled with gold bars.

He’d play Fats Domino, Connie Francis, and Bobby Darin on the eight-track – in the house, in the yard, in the car. Wherever he was, he brought his music (the way I’d later bring mine). And we’d sing. He’d rib me for “knowing all the words all the time”.

My grandmother would eventually coerce everyone into a round of Santa Claus is Coming to Town, complete with hand motions, though Christmas carols already crackled through a radio by the sink.

She would convince you that you needed a second plate of food – or a third – while my mother and aunt scuttled to clean the dirty dishes and clear the table.

My father and uncles would sit in the living room, talking in a frequency only understood by sports fans, or complained about ‘the alternator’, or ‘the radiator’, or the politicians. It was a language I would grow to learn.

And then my cousins and I would retire to an empty room or hallway to comb our Barbies, change their clothes, compare our Cabbage Patch Kids, and, of course, make up a dance to perform, mid-kitchen, for the entire family. We’d cartwheel and split in our footed tights, making the best of our nervous energy as we practiced.

From the kitchen, we’d hear a stray “What the Christ?” or a “Vaffanculo!” from my grandmother, which I won’t translate, because it’s Christmas. And then she’d laugh, with her hand covering her heart, talking fondly of her parents, or the fixes my aunts and uncles got into, as if she were trying to keep her joy from spilling out. She had the most beautiful laugh. It matched the twinkle in her eyes.

And my grandfather would play his eight-tracks, and snap his fingers, and take his Polaroids. And they’d slip me quarters and candy, even though it was Christmas Day.

Then I’d go home, bleary-eyed, with a bag full of torn up boxes, and sleep. And spend the rest of the week feeling the magic slowly wear off.

They’re all just echoes now – the eight-tracks, the aluminum pans, my grandmother’s laugh. Sometimes I close my eyes and wonder how their voices would sound in my house, whether she’d yell, “Steph, what the Christ?” if I wasn’t serving the soup fast enough, or if my grandfather would provide my kids a steady stream of bread and butter, just like he did with us.

And even though I’d sometimes give my left leg to have them back for a day – even a few hours – I know that they’re here. They’re here whenever I kiss my kids goodnight, when I cook a meal, when I smile at a stranger. They’re here.

So if you’re at all feeling like you may be missing the joy of those passed this season, rest assured that you’re not.

It’s just inside you now, and all around you.