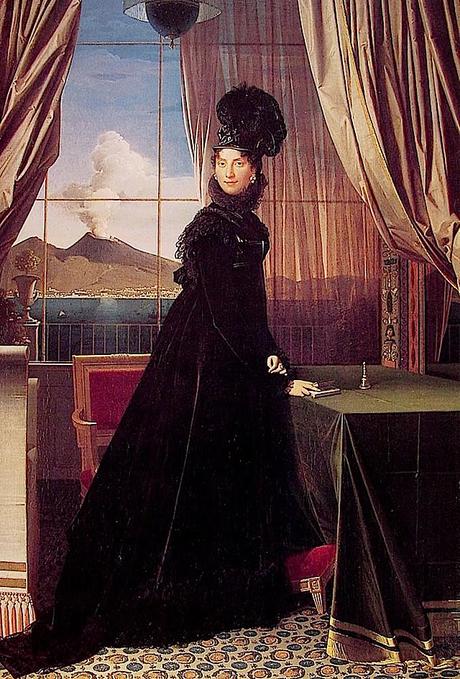

Caroline Bonaparte Murat, Wicar, 1809. Photo: National Gallery of Umbria, Perugia. Difficult and mean though Caroline may well have been, I absolutely adore this portrait.

It’s been a while since we had a bit of Bonaparte history on this blog, so I thought I’d take this opportunity to post about Maria Annunziata Caroline Bonaparte (always known as plain Caroline), who was born on this day, 25th of March, in 1782 and was Napoleon’s youngest sister. Like all of the Bonapartes, she was incredibly vain, so there’s lots of lovely portraits of her about – I always get the feeling that Napoleon and his family saw portraiture, and especially in a grand full length style, as yet another way to underline their position as new royalty and make them look a bit less like the parvenu interlopers that they most definitely were.

Oh, I shouldn’t be so scathing really about the Bonaparte siblings but they haven’t really had a great press have they? Bonaparte’s bunch of rapacious sisters have had a particularly harsh time of it when it comes to the judgment of posterity, but then I reckon they mostly brought it upon them themselves by not being altogether pleasant or particularly gracious people and of course they suffer in contrast to Joséphine and her daughter Hortense, who are generally touted as being their superiors in every possible way. I suppose they are the nineteenth century equivalent of the Geldof sisters or the Kardashians – famous simply because of who they happen to be related to and not particularly respected by anyone because of this.

Caroline Bonaparte Murat, Gérard, 1808. Photo: Château de Fontainebleau.

We’re talking about Caroline though today – who was perhaps the least nice of Napoleon’s sisters, although let’s not hold that against her. Caroline was raised in relative obscurity in Corsica until the mid 1790s when her brother, who was then rising up through the military ranks on his way to absolute power, arranged that she come to France for her education. Lucky Caroline, who was virtually illiterate, was sent to Madame Campan’s school in St Germain en Laye along with her new niece-in-law, Hortense de Beauharnais, who was a year younger.

Tempestuous, wilful and passionate like most of her siblings, the adolescent Caroline, who was apparently very pretty with blonde ringlets, huge eyes and all the rest of it, fell madly in love with one of her brother’s friends and fellow officers, a noted dandy with splendid curling hair and lovely mutton chops by the name of Joachim Murat and went on and on at Napoleon, who didn’t really approve of Murat as a brother-in-law, until he agreed to let her marry him.

Presumed portrait of Caroline Bonaparte Murat, unknown artist. Photo: Château de Malmaison.

The seventeen year old Caroline became Madame Murat at her brother Joseph’s house at Mortefontaine on the 20th of January 1800 and was no doubt wildly happy at first with her dashing and extremely charming husband, who was exactly fifteen years her senior (yes, it’s his birthday today too!). I imagine the pair of them as being rather like Lydia Bennet and Wickham – she, all flashy dresses, showing off and wild high spirits and he, slightly embarrassed and not altogether approved of in his military uniform. Like the Wickhams, the Murats lived well off the back of other people’s achievements, moving into the grand Hôtel de Brienne, close to the Tuileries and accumulating enough wealth to make a huge and very extravagant splash in Parisian high society. However, unlike the Wickhams, the Murats were well matched – intelligent despite their deficient educations, sensual, bold, dynamic and fiercely ambitious, they made a formidable team.

The couple’s first child, Achille, was born a year after their wedding on the 21st of January 1801 and was followed by three more children: Marie Letizia (born in April 1802); Lucien (born in May 1803) and Louise (born in March 1805).

Caroline Bonaparte Murat and her daughter Letizia, Vigée Lebrun, 1807. Photo: Château de Versailles.

Madame Vigée-Lebrun encountered Caroline in Paris at this time after she commissioned by Napoleon himself to paint a portrait of his sister and had this to say about her in her memoirs: ‘I could not conceivably describe all the annoyances, all the torments I underwent in painting this picture. To begin with, at the first sitting, Mme. Murat brought two lady’s maids, who were to do her hair while I was painting her. However, upon my remark that I could not under such circumstances do justice to her features, she vouchsafed to send her servants away. Then she perpetually failed to keep the appointments she made with me, so that, in my desire to finish, I was kept in Paris nearly the whole summer, as a rule waiting for her in vain, which angered me unspeakably. Moreover, the intervals between the sittings were so long that she sometimes changed her mode of doing her hair. In the beginning, for instance, she wore curls hanging over her cheeks, and I painted them accordingly; but some time after, this having gone out of fashion, she came back with her hair dressed in a totally different manner, so that I was forced to scrape off the hair I had painted on the face, and was likewise compelled to blot out a brow-band of pearls and put cameos in its place. The same thing happened with her dress. One I had painted at first was cut rather open, as dresses were then so worn, and furnished with wide embroidering. The fashion having changed, I was obliged to close in the dress and do the embroidering anew. All the annoyances that Mme. Murat subjected me to at last put me so much out of temper that one day, when she was in my studio, I said to M. Denon, loudly enough for her to hear, “I have painted real princesses who never worried me, and never made me wait.” The fact is, Mme. Murat was unaware that punctuality is the politeness of kings, as Louis XIV. so well said.‘ Oops. That’s YOU told, Madame Murat.

Jealous, egotistical and competitive by nature, Caroline indulged in life long rivalries with the other women in the Bonaparte circle – in particular her sisters, with whom she vied for honours, titles and money and her sisters-in-law, Joséphine and Hortense de Beauharnais, whose impeccable aristocratic elegance and demeanour inspired the most terrible envy in the much less well bred Bonaparte sisters. Worse was to come though when Napoléon’s meteoric rise to power brought REAL princesses into the Bonaparte family circle – we can only imagine Caroline’s chagrin every time their regal deportment showed her up, which must have been fairly frequently as, like her sister Pauline, Caroline was a terrible attention seeker who could never resist making herself the cynosure of all eyes.

Caroline Bonaparte Murat, Isabey. Photo: Musée Louvre.

Her spite towards Joséphine and Hortense knew no bounds though as she saw Napoleon’s fondness for his well behaved and very loyal Beauharnais in laws as a direct threat to the interests of the Bonaparte family, particularly herself. Although at first she pretended to be fond of Joséphine and Hortense, who was after all at school with her, once she was married and free to do as she pleased, the gloves came well and truly off and Caroline did everything in her power to undermine Joséphine’s position – even going to the lengths of setting her brother up with a new and very beautiful mistress, Eléanore Denuelle. Of course, Caroline couldn’t have predicted that Eléanore would become pregnant, but that she did so and then became mother to Napoléon’s first child, was an epic blow at the very heart of the Bonaparte marriage and a direct trigger for the events that would eventually end in their divorce in 1810.

However, she herself was to become royalty when her brother appointed her husband Joachim first Duke of Berg and Cleves in 1806 and then King of Naples in 1808, making Caroline the Queen in the place of the now deposed and exiled Maria Carolina, sister of Marie Antoinette. This must have seemed like a major victory for a once illiterate Corsican girl and she entered into her new position with aplomb, never letting anyone forget for an instant that she was Queen now and no doubt being unutterably insufferable about it.

Caroline Bonaparte Murat before the Bay of Naples, Gérard. Photo: Fondation Dosne-Thiers, Paris.

As might be expected, things started to take a downward turn when Napoleon’s career began its heroic nosedive in 1812 with the abortive attempt to invade Russia followed by the disastrous (for Napoleon at least) Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, after which Joachim Murat, aided and supported by his wife who was effectively turning her back on her brother by doing so, began to make secret treaties with the Allies to ensure that he would retain the throne of Naples and everything else he had clawed for himself upon Napoleon’s now seemingly inevitable fall from power. His schemes were successful but came unstuck when his brother in law made a last ditch comeback tour during the Hundred Days in 1815 and Joachim decided to take his side, putting everything at risk in a tremendous gamble on things coming right at last for the beleaguered Napoleon.

The gamble failed and Joachim Murat fled to Corsica before being arrested by the newly restored King of Naples, Ferdinand I and summarily executed for treason on the 13th of October 1815, shouting the command to fire himself with a splendid: ‘Soldats! Faites votre devoir! Droit au cœur mais épargnez le visage. Feu!’ (‘Soldiers! Do your duty! Straight to the heart but spare the face. Fire!’ – Ah vanity, can you imagine what Joachim and Caroline would be like now in our present ‘selfie’ culture? Nightmare.)

Caroline Bonaparte Murat, Counis. Photo: Musée de la Maison Bonaparte, Ajaccio.

Before he died so bravely, Joachim is reported to have pulled out a miniature of his wife and kissed it with great aplomb, something that must have been a great comfort to her as she went into exile in Trieste, leaving her Naples kingdom and the Bonaparte glory days behind forever and vanishing into relative obscurity. Much later on, in 1830 she would marry again, to the superbly named Francesco MacDonald, who had been Minister of War in Naples in 1815, before dying in Florence in May 1839 at the age of fifty seven.

Caroline Bonaparte Murat, Ingres, 1814. Photo: Private Collection.

Before I go, I’d like to say a MASSIVE thank you for all the support yesterday while I was launching my fifth novel From Whitechapel. I really was completely blown away by all the lovely messages all over social media and really hope that those of you who buy a copy are not disappointed! The book is now available for kindle for £1.86 from Amazon UK and $2.99 from Amazon US.

******

‘Frothy, light hearted, gorgeous. The perfect summer read.’ Minette, my young adult novel of 17th century posh doom and intrigue is now £2.02 from Amazon UK and $2.99 from Amazon US.

Blood Sisters, my novel of posh doom and iniquity during the French Revolution is just a fiver (offer is UK only sorry!) right now! Just use the clicky box on my blog sidebar to order your copy!

Follow me on Instagram.