Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971)

Director: Robert Bresson

Cast: Guillame des Forêts, Isabelle Weingarten

Runtime: 79 minutes

My Rating: ★★★

In Short: An interesting and Bressonian telling of Dostoevsky’s great story

Fyodor Dostoevsky’s short story “White Nights” has been adapted into film by several directors, most famously Luchino Visconti, and so when the great Robert Bresson adapted it into his film Four Nights of a Dreamer in 1971, no one was really surprised or all that interested. After all, it would be incredibly hard to top Visconti’s brilliant version starring Marcello Mastroianni and Maria Schell. But Bresson, who had previously adapted Dostoevsky stories into Pickpocket and A Gentle Woman (and whose future films, particularly 1983’s L’Argent, would have elements of the great writer), does justice to the tale in his own interesting ways, and while Four Nights of a Dreamer is one of my least favorite Bresson movies, it certainly has its moment and is filled with Bresson’s trademark bleak style, if admittedly to a somewhat lesser degree.

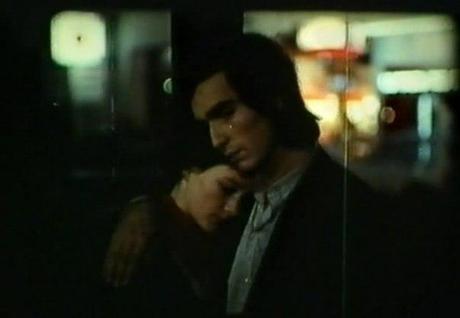

The classic story is the same: a young man saves a woman from jumping off a bridge. They become lovers. He learns that she was waiting for her ex-lover to meet her that night on the bridge, and he never showed. The young man and the woman spend four nights together, but then her old lover returns. Who will she choose? The story always ends the same, with the woman choosing her ex-lover, but a few things about the way Bresson expresses this don’t quite add up. I understand that the woman, Marthe, is indecisive about her love, but how is it that moments after she professes a deep love for the young man, Jacques, and a hatred for her lover that abandoned her, that she can simply jump into the old lover’s arms without a second thought? I don’t think even Bresson knows, and it is one of the big flaws of this otherwise mostly very good movie.

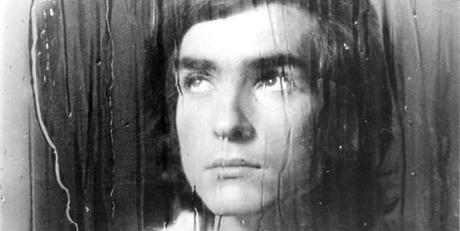

Jacques is a painter, a passionate artist who expresses his worldview in dialog that might belong in a Godard film, but seems suitably at home here with Bresson. As well as painting, the young man also records sounds. One day, sitting in a park recording birds, he notices how embracing lovers dig their fingers into each other’s skin, and coldly rejects his own arousal in a way only a Bresson actor could do so subtly. The actor that plays Jacques, Guillame des Forêts, a non-actor who despite his theatrical name, never made another film, reminded me distinctly of a mid-30s Jean-Pierre Leaud, who at the time was working for Truffaut on Day for Night. Leaud was famous for his role as the inimitable teenage and young adult romantic Antoine Doinel, the curiously cute but emotionally guarded angst-ridden man who we never could be quite sure of. Not only does Forêts resemble Leaud, he seems to act in the same way, quiet and withdrawn yet vocal about his passions. In a small detail that seems exemplary of the French New Wave effect, Forêts’s character Jacques has a tape recording of himself saying his lover Marthe’s name over and over. When he is without her, he simply presses play and listens to her name. It is enough.

There is a curious sequence reminiscent of the Passion of Joan of Arc cinema scene in Godard’s Vivre sa Vie, though Bresson’s version of the scene has a much lesser effect and is more forgettable, but still it struck a chord with me. Marthe is forced to attend a film premiere for a movie she is uninterested in. We are shown one sequence of a film in which a man is shot several times and writhes around in pain, dying as blood forms in a circle around him. The interesting thing about this sequence (in which the cinematography made it obvious Bresson directed this film-within-a-film) is how disturbingly gory it is and how long it lasts. It is uncomfortable for the audience in the theatre, and the viewer at home. Some may think it out of place, and I can’t disagree. I don’t know what it means, but I do think Bresson put it there for a reason, and I believe it works. The explanation I’ve come up with is that the man that is shot represents Jacques, and the film is a foreshadowing of the metaphorical “bullet to the heart” that he is to take when Marthe chooses her old lover over him. Indeed, at the end of the film when Jacques is rejected, he does not die but retreats into his art, painting obsessively. This is interesting. Bresson usually kills his main characters or has them kill themselves, but he rightfully realized that there would be no reasonable way to kill Jacques, but to satisfy himself, Bresson included this wicked sequence of a man being killed so that we must still exit the theater feeling that typical Bressonian grimness of the witnessing of a saddening death. Why else would Bresson let the sequence go on so long? Behind the camera, he was grinning.

Bresson’s later films, typified by the use of colour, seem to me to be a noticeable change from his earlier ones. They retain his easily identifiable directorial skill and style, but seem to lack in some ways the grace and beauty of the earlier films. Certainly there are no sequences in his color films as saddening as the endings of Au Hasard Balthazar or Mouchette, and the deeply saddening cinematic perfection of Diary of a Country Priest seemed a far, distant memory. Four Nights of a Dreamer, the follow-up to the similar A Gentle Woman, are blinding steps forward into the realm of the 70s, a more sobering color decade after the erratic but brilliant black-and-white 60s. In Four Nights of a Dreamer, Bresson makes use of modern music in numerous scenes, and there is also a surprisingly frank amount of nudity (one scene follows the female lead character naked for at least a minute or two, for no important reason). While Bresson would redeem his slow fade into obscurity with 1983’s brilliant L’Argent, his 70s films for the most part seem a lot less powerful and a lot more wasteful. Some of them seem to just race right to the conclusion, instead of taking their time in the wonder of Bresson’s mise-en-scène, a style and atmosphere that made so many of his best films so amazing.

Previous Films in the Bresson-athon:

Les anges du peche (1943)

Les dames du bois de boulogne (1945)

Diary of a Country Priest (1951)

A Man Escaped (1956)

Pickpocket (1959)

The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962)

Au Hasard Balthazar (1966)

Mouchette (1967)

Une Femme Douce (1969)

Next Film:

Lancelot of the Lake (1974)