Long term readers (you poor poor things) may well recall that around a year ago, I came clean about my shameful lack of knowledge about the Second World War. This was not entirely my fault – despite going to three different secondary schools, all of which have since been ranked as ‘outstanding’ by Oftsed (God only knows how or why), I didn’t have any formal history lessons at all until I started my Early Modern History A Level (i.e. covering the Italian Wars to the English Civil War and not the Modern History A Level that most people default to, which of course would have gone some way towards ensuring that I knew at least something about WWII) at sixth form and although I have been OBSESSED with history for as long as I can remember, my Aspergers means that I have always tended to cherry pick my eras and subjects and then totally immerse myself in them before moving on to the next, while ignoring anything that I found boring – a bit like a hideous alien horde hopping on to a planet and laying waste to it while making free with all of its resources before zooming off to the next one.

Anyway, having realised with some horror that Dunkirk and D Day were not actually the same thing at all, I decided that enough was quite frankly ENOUGH and that I was going to have to do something drastic to alleviate my painful ignorance. I started off with some general histories of the war and then decided to give myself a break and reverted back to my usual cherry picking ways, with books about specific aspects of the war that I found interesting. A year has passed and I would have to say that I feel pretty confident about my WWII knowledge now, but it remains an ongoing project as I still have an immense backlog of books waiting on my Kindle, mostly about the fall of Berlin, which has really interested me since we visited the city last October.

However, one of the topics that interested me the most was the top secret work of the codebreakers at Bletchley Park. Thanks to my Aspergers, I’ve always considered Alan Turing a bit of a personal hero, admiring his genius and sincerely deploring the way he was treated after the war. It’s absolutely shameful. My own maths skills are really nothing to be writing home about as I have dyscalculia, but no doubt thanks again to my Aspergers I have a certain facility when it comes to learning languages and by extension, I suppose, cypher breaking, which I see as much the same thing and so I naturally feel a certain kinship with the people who worked at Bletchley during the war. I’d like to think that I’d have ended up there myself, but I expect everyone thinks that.

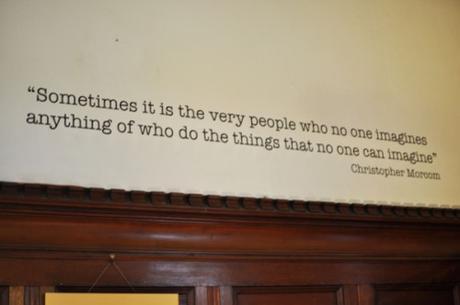

I first went to Bletchley about ten years ago for a wedding and had a brilliant time running about the mansion in the middle of the night and drunkenly playing Secret Spies with my husband (we had only been married about a month ourselves back then) but although we’ve often talked about going back, it didn’t actually happen until about a month ago when after several postponements we chucked our children in the car and drove to Oxfordshire. Our son is in the process of being potentially diagnosed with Aspergers at the moment and remembering how we struggled with it ourselves, we thought that it might do him good to learn a bit more about the time when geeks used their special geeky super skills to save thousands of lives and bring the war to an end. It did me good too, I’ll admit, as there’s often days when I feel clumsy and useless and just plain weird and visiting Bletchley really served as a reminder not just of how bloody lucky we all are to live the way we do now and how much we have to be thankful for but also that maybe I’m not a total waste of space after all and that although obviously I’ll never be as useful as the Bletchley people, I can still put my own relatively feeble geeky super skills to helpful use too.

When we first visited Bletchley Park, it was pretty ramshackle with just the mansion and some huts. Things have really changed since then though and we were astounded and impressed by how much it has grown and been developed in the last decade, thanks to donations from Google and other groups. Visitors now make their way through a large and spacious visitor’s centre, which has a pleasingly utilitarian war time color scheme going on, with notices stencilled on the walls and so on so that you too can pretend that you’re in a top secret WWII department. It’s all been very well planned out and lovingly put together so that it is informative (and fascinatingly so) while at the same time retaining a certain secretive ambience, which is extremely effective at evoking at least a partial sense of what Bletchley must have been like in its heyday during the war, when several hundred people worked there.

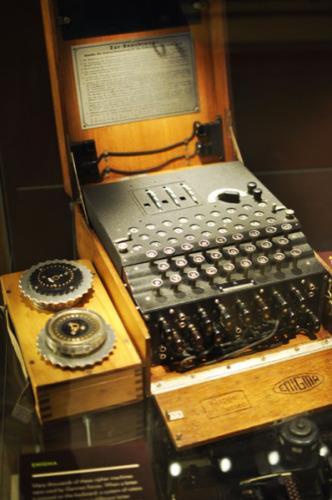

A visit to Bletchley begins with the exhibition in the visitor’s center in Block C, which was opened quite recently by the Duchess of Cambridge (whose grandmother worked at Bletchley Park during the war) which is really fascinating and gives a great introduction to the work carried out there during the war and the impact that it had. Although it is obviously geek heaven there, I would say that everything is perfectly pitched to be accessible and understood by everyone, engaging even young visitors in the story of Bletchley Park with some really well designed interactive displays. It’s always thrilling, of course, to get a proper look at an Enigma machine, which the Germans used to send coded messages and which the codebreakers at Bletchley so famously cracked as part of their Ultra intelligence system, and there’s one in the pretty much the first display cabinet that you see. It looks pretty innocuous, a bit like a weird old fashioned typewriter, but the ability to break its codes saved millions of lives and ended the war several years earlier than it might otherwise have dragged on for.

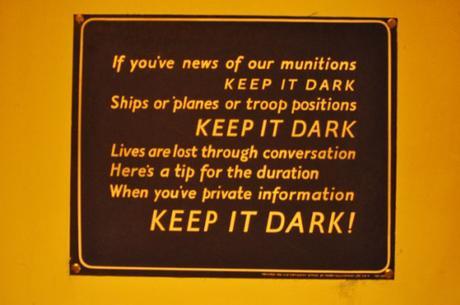

The truly remarkable thing is that the Germans didn’t find out that we had cracked their codes until the early 1970s, ages after the war had ended, as the work at Bletchley Park was kept so completely secret. It’s also noteworthy that there was no German equivalent to Bletchley as they had no central organised codebreaking department and certainly nothing like the technology produced by Turing and his colleagues, with the result that they did not have quite the same level of success when it came to breaking our codes in return. Hah. In THEIR faces.

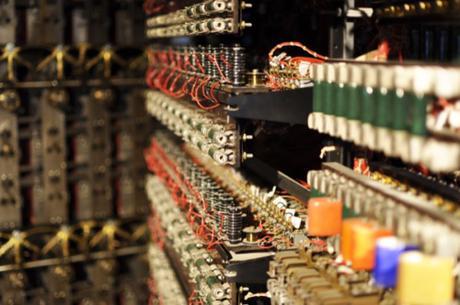

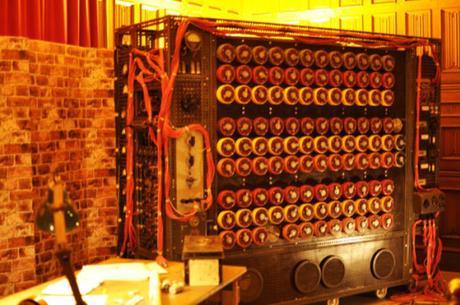

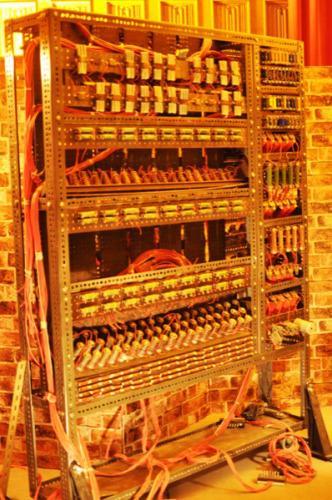

Moving on from the visitor’s centre, the story of Bletchley Park is told via really fascinating displays in different huts on the site, with perhaps the largest display in Block C, which explores the work carried out at Bletchley in more detail and the impact that it had on the war. I wouldn’t say that I am massively geeky when it comes to actual equipment, but I was absolutely enthralled by this display, which involved a reconstructed bombe machine, the electro-mechanical device that was used to break Enigma and a lot of information about the processes involved. I was particularly intrigued by the section about Japanese code breaking, which must have been extraordinarily challenging at a time when people did not commonly learn Japanese – the staff at Bletchley were given special language lessons to get them up to speed as once the codes were broken, they obviously had to be translated from whatever language they were originally written in. This is why so many young debutantes, girls of good families, were employed there as they were commonly already fluent in other languages, particularly German and French.

I was really fascinated by the displays focussing on everyday life at Bletchley, which was home to several hundred people at its peak. Bound to silence by the secret’s acts that everyone had to sign and working at all hours of the night and day in an extremely tense and nerve-wracking atmosphere, they clearly liked to have fun whenever the opportunity arose. Most of the Bletchley staff lived off site and came in every day for their shifts then left again, but the main mansion about which the community of huts and blocks gradually appeared, seems to have been something of a hub for a really quite active social life. It’s not really surprising though: the staff at Bletchley were mostly pretty young and comprised a mixture of military staff (there to give context to the missives interpreted by Ultra), academics like Alan Turing and whole troops of fresh faced young women, some of whom were Wrens, there to work with the massive, noisy bombe machines in their special hut.

The really remarkable thing is that although everyone socialised together, enjoying dances, theatrical performances, chess clubs and so on, apparently no one talked about their work with people outside their own hut and usually didn’t know what went on outside their own particular section. Apparently even the people in charge of the operation were pleasantly surprised by the atmosphere of polite discretion and the fact that even the townsfolk, many of whom had Bletchley Park staff lodging with them, had absolutely no idea what went on there.

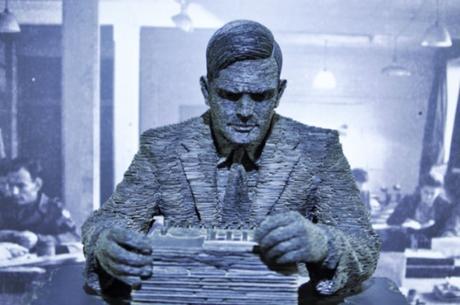

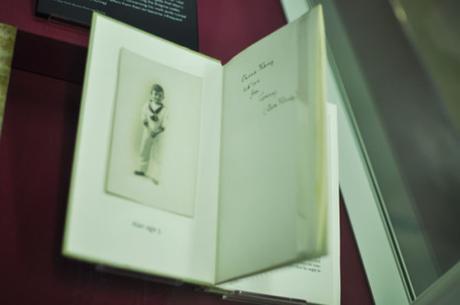

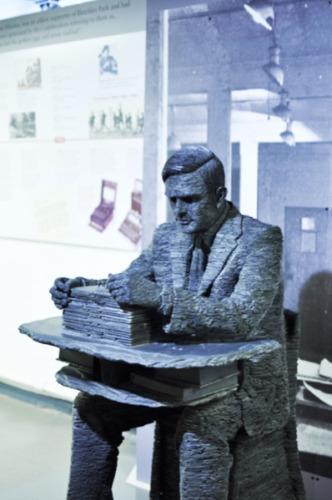

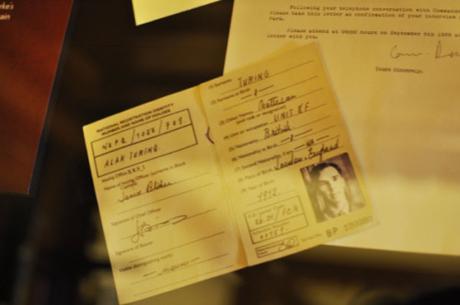

Of course, I was most interested in the section devoted to Alan Turing and there’s a pleasing selection of items on display, which either belonged to him or were related to his work at Bletchley Park, such as some of his notebooks, his teddy bear and even an old school report. It could have been really dry, but instead gave a really illuminating and sensitive insight into Turing’s mind and personality. Far from being a misfit loner, he was actually popular, funny and well liked, even if he had his odd eccentricities, such as chaining his mug to a radiator to stop people stealing it (I think this is just sensible though). As well as the display, there’s also a really beautiful statue of Turing close to the reproduction of the bombe machine that he worked on. I’m not sure, obviously, what he would have made of the fact that he is now regarded as a hero, but I hope that it would have pleased him, even if he thought it was a lot of nonsensical fuss.

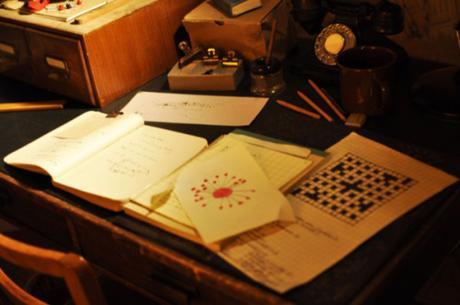

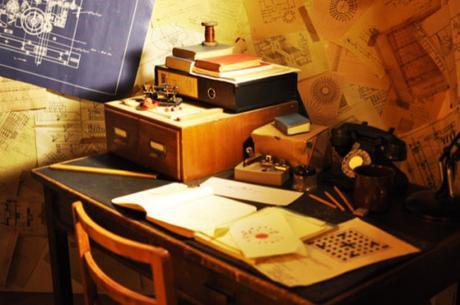

For a more intensive look at the work carried out at Bletchley Park, visitors can now visit some of the huts, Huts 3, 6 and 8 where Turing and his colleagues worked together to crack Ultra, decode and translate encrypted German messages and then assess how useful they would be to the War Office. The huts are small and cramped, much like school port cabins, although much bigger and each room has been restored to how it probably looked in the 1940s, when intelligence operations were carried out there, so it is possible to see Alan Turing’s office (complete with mug chained to the radiator and sports gear in the cupboard) in Hut 8 (where naval codes were broken) as it may have looked during his occupancy. There’s lots of information in each room about what each section did and the people who worked there, often well into the night, puzzling over the messages and trying to extrapolate as much important information as they could out of them before midnight, when the Enigma code was changed by the Germans and their arduous work began again.

In the dimly lit, claustrophobic atmosphere of the huts, it’s still possible to feel just how it must have felt to work at Bletchley during the war, knowing that countless lives depended on your accuracy and the decisions that you made. The people who worked there must have had nerves of steel, although I suspect that the likes of Turing and his academically minded colleagues probably got themselves through it by approaching the process as a sort of abstract yet fascinating mental puzzle to be worked out, rather than a matter of life or death.

As with elsewhere on the site, there’s plenty of information for visitors of all ages in the huts, with interactive displays, clearly laid out information in each room and well thought out use of projection and sound to convey what life was like at that time. It’s obvious that a lot of thought has gone into the best way to present Bletchley’s story and I have to say that it all works really well. It would be really easy for the displays to be very dull and incomprehensible to people who are not of a technical bent, but instead there’s a fresh, upbeat and inclusive feel to the site that makes it all really interesting and, crucially, easy to understand even if you rolled up not knowing a thing about bombe machines and encryption. The people who work there are also extremely helpful and obviously take immense pride in the site, so they love to answer questions and show stuff off. I thought it was great.

After this we went off to look at Hut 11, where the famous bombe machines were housed. There were several of them in this relatively small, dark space and they stank of oil and made such a racket that the young Wrens who worked with them dubbed the hut, a ‘hell hole’. Although efforts have been made to replicate this experience as accurately as possible, it has obviously been toned down a bit for the sensibilities of modern visitors, although it was certainly still noisy and claustrophobic enough to give a sense of how awful it must have been for them. There were large full sized models of several bombe machines and also projections of ‘Wrens’ from the period talking about their work and what it was like at Bletchley, to work in such secrecy and under such pressure. Many of the women who worked there had probably never done any sort of manual labor before so it must have been a steep learning curve to learn how to use such formidable looking machinery and know that so much depended on doing so as accurately as possible.

Of course, Bletchley Park and Alan Turing have been all over the media for the last year, thanks in part to The Imitation Game, which starred the ubiquitous Benedict Cumberbatch (seriously, he and Mark Gatiss are EVERYWHERE right now, it’s getting weird) as Alan Turing and focused on his work at Bletchley Park. Cumberbatch’s sensitive, sympathetic and intelligent portrayal of Turing has been rightly praised and while the film played fast and loose with the actual facts, it certainly served to underline the importance and intensity of the work that was carried out at Bletchley and the atmosphere on the site during the war. It also brought even more attention to the unfair way with which Turing and other homosexuals were treated. As a historian, I am pretty much inured by now, I suppose, to most of the less pleasing things that went on in the past (and this encompasses all manner of iniquity and woe). I don’t condone it but I accept it, I suppose, because I also accept that the past is a different country and so on. However, I simply just can’t get my head around the barbaric way that homosexuals were treated, even as recently as the 1950s, when Turing was arrested for participating in homosexual acts and opted for chemical castration instead of imprisonment. It’s shameful and wrong.

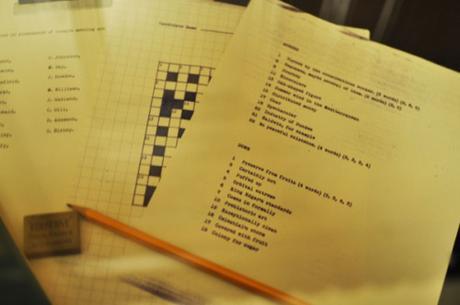

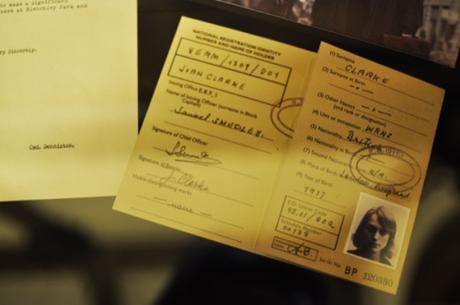

Although the bulk of The Imitation Game is set at Bletchley Park during the war, only a small amount was actually filmed there, including the bar scene, which was filmed in the ballroom at the Park, which currently hosts part of an exhibition about the film, with an excellent display of costumes and props from the production, including Turing’s bombe machine ’Christopher’, costumes worn by both Benedict Cumberbatch and Keira Knightley and the crossword puzzle used by Turing for recruitment purposes in the film and which leads to Joan (Knightley’s character working at Bletchley).

It’s all beautifully presented and with the film’s soundtrack swelling overhead, it’s hard not to be moved afresh by this sympathetic take on Turing’ story. It’s also a nice touch that the bar from the film has been reconstructed in the ballroom so you can, sort of, imagine yourself on set. I’ll admit that I actually wasn’t sure about going to see The Imitation Game when it came out last year, however interviews with the cast and in particular Benedict Cumberbatch, who seems to feel just as strongly about the unfairness of Turing’s treatment as I do, reassured me that his story was in safe hands. I’m now really glad that I went, even if I cried my eyes out from start to finish as I found it so moving. Even though it was made up of film props and so not actually real items, the exhibition really moved me too, perhaps because it was clear from the objects on display that a lot of love and care went into the film and had clearly been motivated by their own admiration and, dare I say it, affection for Alan Turing.

Ah, I feel really choked up again now. Oh dear. I absolutely loved our day at Bletchley Park; it’s such a special place that everyone with an interest in either the history of WWII or computing should try to visit as it really is fascinating, no matter how geeky you are. I came away feeling profoundly humbled by the behind the scenes efforts and the dedication and sheer amazing genius that won the war for the Allies – it really is an inspiring and wonderful story and one that Bletchley Park manages to convey brilliantly. It could so easily have been really dull or, worse still, unbearably patronising as the story of the codebreakers necessarily involves a lot of technical detail, but instead it’s never anything less than fascinating, especially as they make an effort to underline the human effort behind the machinery.

If you want to know more about daily life at Bletchley Park during the war, I really enjoyed The Secret Life of Bletchley Park: The History of the Wartime Codebreaking Centre by the Men and Women Who Were There

Ps. Go and type ‘Bletchley Park’ into Google and see what happens. So amazing.

******

Set against the infamous Jack the Ripper murders of autumn 1888 and based on the author’s own family history, From Whitechapel is a dark and sumptuous tale of bittersweet love, friendship, loss and redemption and is available NOW from Amazon UK

‘Frothy, light hearted, gorgeous. The perfect summer read.’ Minette, my young adult novel of 17th century posh doom and intrigue is available from Amazon UK

I don’t have adverts or anything like that on my blog and rely on book sales to keep it all going and help pay for the cool stuff that I feature on here so I’d like to say THANK YOU SO MUCH to everyone who buys even just one copy because you are helping keeping this blog alive and supporting a starving author while I churn out more books about posh doom and woe in the past! Thanks!

Follow me on Instagram.