Source: Hardcover borrowed from neighboring library

Summary: When chess originated in India, some 1500 years ago, there were no female pieces on the board. Chess was a battle game, and, in that time and place, women didn't participate in battle. The pieces continued to represent men and animals as it passed through Persia and the Arab peninsula.

Summary: When chess originated in India, some 1500 years ago, there were no female pieces on the board. Chess was a battle game, and, in that time and place, women didn't participate in battle. The pieces continued to represent men and animals as it passed through Persia and the Arab peninsula.

When the game reached feudal Europe, the pieces were modified to represent elements of medieval European courts. The elephant transformed into a bishop (or jester or standard bearer, depending on the country). The chariot became a tower. The vizier, an advisor to the king, became the queen. The queen, like the vizier, was originally the weakest player on the board. But, by the reign of Isabella of Castile of Spain, in the late 15th century, she was the most powerful piece.

The topic of Birth of the Chess Queen is written as a question about the chess queen on the first page of the Introduction:

How did she come to dominate the chessboard when, in real life, women are almost always in a position of secondary power? (p. xvii)

After sharing the history of chess (all new to me) and its origins in India, Birth of the Chess Queen, explains how the queen entered the chess board in Europe, taking the place of a military advisor, the vizier. In the Middle Ages, four things grew together:

- The rise of the chess queen

- The rise of power for real-life queens

- The rise of the veneration of the Virgin Mary

- The rise of courtly love traditions

Together, these developments produced the powerful chess queen that we know and love today.

Thoughts: Birth of the Chess Queen was the selection for last night's meeting of The Madwoman's Book Club, a production of the Women's Program of the US Chess Federation. I meant to attend, but circumstances got in the way. I'm glad that prompted me to read this book, however.

That group, of course, attracts chess players. But here's a passage that will please my fellow booklovers about a late thirteenth century book, The Book of Chess, by Italian Jacobus de Cessolis, a Dominican friar.

The popularity and influence of The Book of Chess was remarkable, and it became the equivalent of a late Middle Age best-seller. It was translated into French, Italian, German, Catalan, Dutch, Swedish, and Czech, and then, with the advent of the printing press in 1456, it spread even further. The Great English printer Caxton published it immediately after the Bible. Every princely library during the late fifteenth century would have owned one or more copies, and even today some two hundred manuscripts have survived, not to mention the many printed editions. Of all the manuscripts and published books circulating around 1500, only the Bible existed in greater numbers. (pp. 71-2)

The book ends with questions about women and chess in modern times. Just as the queen became more powerful on the board, the game began to be played by fewer and fewer women.

Since (as I complained about on Thursday) I experienced sexism in my chess development, this passage got me thinking:

Perhaps three words uttered by Xie Jun (Grandmaster and current Chinese Chess Association president) are the most relevant to this debate. When asked to explain women's inferior status in chess, she replied: "They get married." Women do leave chess for marriage, and even if they remain single, they rarely devote themselves exclusively to the game, whereas star male players do little else than play, practice, think, and dream chess. In that women are generally raised to care for families, interact with friends, and take on multiple tasks that support individual and collective life, such obsessive commitment to a game is usually unthinkable. There are, of course, exceptions-for example, in sports like tennis and competitive ice skating-where a few super-women do show the same single-minded devotion as men. But on the whole, women who have the option or the desire to pursue competitive games, and who are willing or able to accept the personal sacrifices exacted by such activities, are precious few. In our society, according to Jennifer Shahade, American Women's Chess Champion in 2002, we consider it weird for a boy to be totally obsessed with chess, but for a girl, "it's not just weird, it's unacceptable."

I just watched Pawn Sacrifice about how difficult Bobby Fischer found it to cope with life. Here's what I'm wondering. Maybe the problem isn't with how we raise girls. Maybe the problem is that we consider that kind of obsession acceptable in boys. Maybe the world would be a better place and men would be happier people if we allowed the highest levels of chess and other single-minded pursuits to be at a slightly lower level so that participants could have a life outside their obsession. What if society considered the wholeness of a person and the wholeness of life to be more important than excellence in a narrow field?

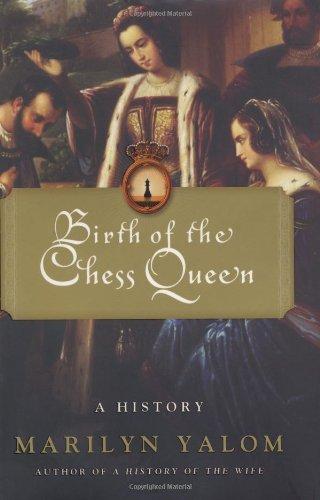

Appeal: I'm surprised that Birth of the Chess Queen wasn't more popular. It's fun to read because the author never forgets that she's writing about a game. There's a lot to learn. I'm surely not the only person who is undereducated about the medieval period, and especially about the women of that time. Illustrations, including color plates, add to the understanding. If you enjoy learning obscure bits of history, Birth of the Chess Queen will hit the spot.

This is my third and final (for now) post on chess recently. If you want to see what brought me here, check out my review of the film Pawn Sacrifice and of the museum exhibit 1972 Fischer/Spassky.

Have you read Birth of the Chess Queen? What did you think?

About Joy Weese Moll

a librarian writing about books