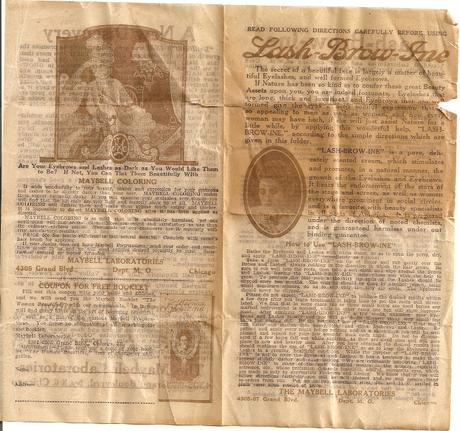

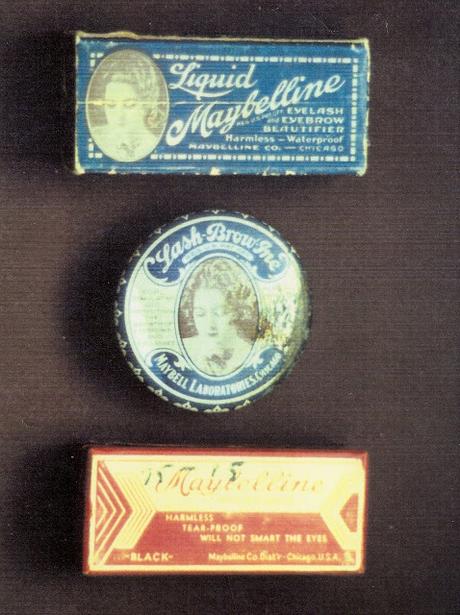

"Before and After" ad for Lash-Brow-Ine, 1915.

In 1915, women were just starting to accept cosmetics again, after avoiding them during the Victorian era. Creams and powders prevailed on the market; however, eye make-up remained all but taboo. In England, social constraints against cosmetics, including lash color, persisted well into the Victorian age, though business was brisk in back-alley beauty services.Proper English ladies of the nineteenth century considered

make–up to be off-limits, the province of prostitutes whose penchant for cosmetics earned them the label “painted women.” Viewed as appropriate only for prostitutes and music-hall performers, make-up was so forbidden in Victorian society a man could divorce his wife for wearing it.Directions inside a box of Lash-Brow-Ine, 1915.

While the American colonies were under British rule, the use of white powder, rouge and lipstick was brisk. After the revolution, cosmetics became political. For example, an unpainted face was a sign of a good Republican.

Women were expected to pinch their cheeks and bite their lips if they hoped to brighten their faces. Men enjoyed greater leeway. They could and did, dye and condition their hair, mustaches and sideburns, often with a touch-up dye for graying hair called Mascaro, from which Tom Later derived the word mascara.

Theda Bara as Cleopatra, in 1917

Women began to enter the work force and began to build independent lives for themselves, making fashion and beauty a bit more robust. At the same time, women were beginning to organize for their political rights, holding suffragist rallies for right to vote. In New York in 1913, more than one parade of Suffragettes marched down Fifth Avenue past a salon owned by a woman named Elizabeth Arden. Arden in New York, along with Helena Rubinstein in England, opened the first beauty salons in the cosmetics business, specializing solely in skin products.