2014 is the 75 year anniversary of Batman’s first appearance in the comics! So, we’re doing a series of articles (called Batman 75) looking back at the Caped Crusader’s history.

When you think of the Joker maybe you flash to images of Cesar Romero’s camp-tastic performance from the old TV show, or Jack Nicholson’s beautifully over-the-top, Prince-loving version from Tim Burton’s Batman. Thanks to his instantly legendary performance, you most likely can’t shake Heath Ledger’s twisted, Oscar-winning take on the character in The Dark Knight, but to many of us there is no Joker above Mark Hamill’s pitch-perfect performance across Batman: The Animated Series and Justice League/Justice League Unlimited. Then again, the work Scott Snyder did with the Joker’s “Death of the Family” story in the comics last year may have set a new bar for just how demented and creepy you could take the character. So, there’s room for interpretation.

Joker in “Death of the Family,” in which his face is literally cut off and awkwardly re-attached mostly because dude is straight up crazy

Maybe more important than which specific version of the character you flash to, when you think of the Joker you think of Batman. He brings chaos to Batman’s order, laughing every step of the way, and serving as the undisputed arch-nemesis to arguably the world’s greatest superhero. However, did you know that we still don’t actually know for sure who really created the character the Joker? Or that if not for a rather astute editor the Joker never would have made it past his first issue? Here’s how it went down:

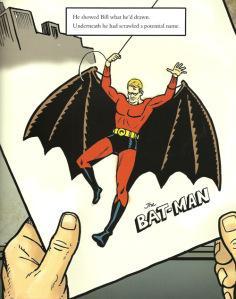

As a reminder, here’s what Bob Kane’s version of Batman would have looked like without Bill Finger’s help

Bob Kane and Bill Finger co-created Batman in 1939, Kane serving as the artist and Finger as the writer. Of course, Finger was just the ghost writer who would not really receive his just due for his far reaching contributions to the world of Batman until after his death in 1974. Either way, Kane had signed a 20-year contract to produce Batman stories for National Publications (early version of DC), but there was a pretty big problem: Kane couldn’t handle the workload. He was already delegating writing duties to Finger (and taking the credit), but he wasn’t proficient enough as an artist to do all of the drawings for the books on his own. So, he hired a 17-year-old journalism student named Jerry Robinson to assist with lettering and background inks. Eventually, Kane just stopped doing any of the drawing whatsoever, with Robinson taking over as the lead artist in 1943.

Beyond his lack of proficiency, Kane needed the help from Robinson because after Batman debuted in Detective Comics #27 in 1939 he was an instant success, quickly transitioning out of the anthology Detective Comics into his own comic book with Batman #1 by spring of 1940. So, the publisher needed as many Batman stories as fast as possible. Batman #1 would feature not just the introduction of The Joker but also Catwoman, in smaller, supporting role. However, Kane, Finger, and Robinson all disagreed until the days they died about who exactly created the Joker.

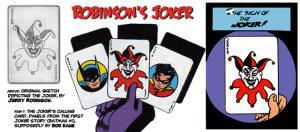

Jerry Robinson’s version of the story:

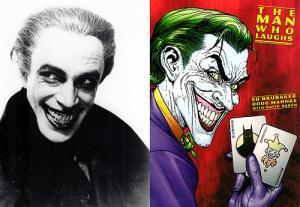

Robinson brought in a drawing he’d made of a playing card featuring the Joker, and showed it to Kane, arguing the card should be the template for their next villain. Or, in his own words from this 2009 interview, “In that first meeting when I showed them that sketch of the Joker, Bill said it reminded him of Conrad Veidt in The Man Who Laughs. That was the first mention of it…He can be credited and Bob himself, we all played a role in it. The concept was mine. Bill finished that first script from my outline of the persona and what should happen in the first story. He wrote the script of that, so he really was co-creator, and Bob and I did the visuals.”

Kane’s version of the story:

Kane came up with the basic idea of a villain called the Joker, and Bill Finger suggested using Conrad Veidt’s character in the silent film The Man Who Laughs (1928), which is about a man punished by being disfigured so that his face is in a perpetual grin, as the visual template for the character. It was after this that Robinson brought in the card, which Kane argued (originally quoted over at DenofGeek), “[Robinson] brought in a playing card, which we used for a couple of issues for him [the Joker] to use as his playing car.”

The Man Who Laughs on the left is the clear real inspiration for the Joker’s apperance

Finger was confused as to when exactly Robinson showed them the card. He did tell a DC editor at the time he felt Kane’s story was closest to the truth.

They’re all dead now. So, we can’t ask them to clarify, not that time would have exactly improved their recollection of the events. However, it’s clear that all three were involved, and considering Kane’s long history of fudging the facts to hog all the credit one might be inclined to believe Robinson more than Kane. That’s the direction comic book historians have gone with it.

What’s more interesting, though, is not who created the Joker but who saved him: Whitney Ellsworth, editorial coordinator for National Publications and Batman #1‘s editor.

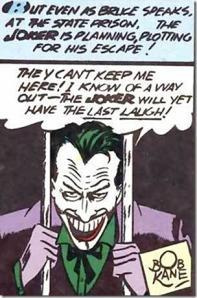

In Batman #1, the Joker announces on the radio his intention to start killing notable figures, and then follows through on his promise, resulting in Batman and Robin capturing him.

Later in that same issue, the Joker escapes from prison and goes on a crime spree stealing jewels. However, Batman gets the drop on him, and as the two engage in fisticuffs the Joker accidentally stabs himself with his own knife.

That was supposed to be the ending – the Joker dispatched after his first appearance, which was a common occurrence in the early days – the villains didn’t usually survive to return for another fight. Ellsworth, as it turns out, had more faith in the Joker than his three creators. Even though the comic was essentially done, Ellsworth took a look at it, and decided it was madness to drop the character so quickly. He forced them to add an extra panel at the very end in which an ambulance driver remarks, “My goodness! He’s still alive!”

Good call, Ellsworth. Interestingly, he also made a significant editorial change to Superman canon that same year. Siegel and Schuster wrote “The K-Metal from Krypton” for Superman #8 in 1940, which not only would have been the first introduction of kryptonite into the comics but also feature a climax in which Clark Kent is forced to reveal his powers to Lois Lane for the alternative would mean her death. Though initially enthusiastic, Lois would grow angrier the more she thought about all the lies Clark had told her since she’d known him. So, she would agree to keep his secret, but her affection for Clark/Superman was gone. For reasons lost to history, Ellsworth scrapped the whole idea even though it was done and ready for publication. Maybe he just decided it was a better idea to stretch out the whole “Lois doesn’t know Clark Kent is Superman” thing for a little longer. Like a LOT longer. Kryptonite would shortly thereafter make its first appearance in Superman canon in the Superman radio show. Who served as liason between the comics and radio show? Whitney Ellsworth.

Source: Brian Cronin’s Was Superman a Spy?: And Other Comic Book Legends Revealed