“I take great joy in scaring my audience. Can’t you tell?”

Alfred Hitchcock – The Master of Suspense

Alfred Hitchcock understood the very nature of suspense. In the case of his 1960 classic Psycho, present a woman taking a shower killed by someone suddenly running into the room to repeatedly stab her? That’s a surprise. Make us watch as a scrawny kid attempts to cover up a murder to protect his mentally unstable, knife-wielding mother? That’s suspense.

Of course, surprise is relatively straight-forward and commonplace in cinema, particularly in the horror genre. A loud musical cue, a person running into frame, tackling a main character or a cat leaping towards the camera– will ilicit the startle reflex . However, it’s an easy scare, simply a Pavlovian response to a stimuli.

Don’t you feel cheap?

The best, most memorable horror films are those that can prolong the terror, extending it until the audience feels it has reached its breaking point. That’s suspense. It’s a more difficult, but more rewarding technique. It is a technique which was perfected by Alfred Hitchcock, whose unique understanding of suspense in film remains unparalled. Other filmmakers attempted similar films, but Hitchcock grasped a better understanding of how to both terrify and enthrall his audience.

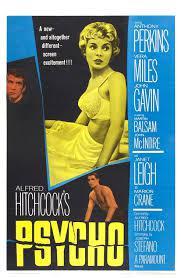

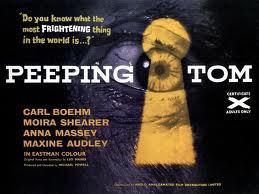

Psycho Vs. Peeping Tom

Compare, for instance, Hitchcock’s classic Psycho which was released in 1960, the same year Michael Powell‘s Peeping Tom, two thematically similar but stylistically opposed slasher films (before the term “slasher film” had been coined, but the label applies).

Both of them were made by British directors, both dealt very heavily with the theme of voyeurism, and both are now regarded as classics. However, Peeping Tom was considered so repulsive and horrific upon its release that it effectively ruined Powell’s career whereas Psycho was a massive hit and further cemented Hitchcock’s power as a director. Why did one do so well when the other failed? It’s all due to psychology, specifically the psychology of the film viewing experience. Powell’s narrative confronts the audience and makes them complicit in the film’s unpleasant scenarios. Hitchcock’s lulls the audience into a false sense of security before pulling the rug out from under them during the film’s climax, cleverly playing upon expectations.

Powell announces to the audience the killer’s identity [SPOILER: it's the film's main character, the titular peeping tom] at the start whereas Hitchcock delays that reveal until the film’s climax. Both require the audience to sympathize with disturbed, vicious killers, but Hitchcock doesn’t alert the viewer to their complicity until the film’s conclusion. Powell prefers to tip his hat at the start. As a result, his film seems more distasteful and upsetting, despite its inherent brilliance. In addition, Powell uses a sharpened camera tripod leg as the murder weapon, while the killer films the deaths as part of a documentary he is creating about the nature of fear. Most of the murders are shown from the camera’s (Read: Killer’s) point-of-view, a technique that became increasingly popular with the 1970s-1980s rise of the teen slasher film, but here was upsetting for the audience. Powell makes the audience culpable in the killings and implicates them in the crimes.

PIcking up on the commentary here? Nah, neither do I.

Hitchcock used a similar technique in his earlier film Rear Window (1954), but there the audience is not condemned in such an emphatic fashion as they are in Powell’s film.

It is not necessarily that Psycho is superior to Peeping Time, or that I personally prefer one to the other. Instead, it is a historical curiosity that both Hitchock and one of his peers would each respectively tackle thematically similar projects in the same year, yet the reactions towards those endeavors would differ so wildly. If you want a good idea for a classic film double-feature, watch these two back-to-back. They makes for fascinating viewing.

The Enduring Popularity of Norman Bates

Bates Motel, about to reach its series midway point, recounts the back story of two characters central to Hitchcock’s Psycho: Norman Bates and his mother, Norma.

The show has a very subtle incestuous undertone. It’s so subtle I bet you didn’t even pick up on it here.

It’s an enjoyable series, if a touch uneven. One might have expected Dexter: The Early Years, with a guiding father figure being replaced by a condemning mother figure. Instead, the showprefers placing Norman Bates in the titular town of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks– a world of sinister, vicious characters and a small town with an idyllic surface concealing an insidious underbelly. This in no way resembles the town as depicted in the original film, in which Norman is the sole sinister figure in a quiet, small town. However, the show is a massive hit for the network, who recently renewed it for a second season.

It’s surprising to discover the name Norman Bates still has the power to fascinate. In a world of Hannibal Lectors, Dexter Morgans, Tony Sopranos, and multiple other anti-heroes who gain the audience’s, if not sympathy than at least fascination, why does Norman Bates still enthrall? I think it all stems back to the infamous shower scene and the scenes that immediately follow it.

With that question in mind, I think the answer does stem from Hitchcock’s decision to (MAJOR, MAJOR SPOILER) kill off supposed lead Marion Crane (played by star Janet Leigh). She is on the run, following a theft of several thoudans dollars of her boss’s money when she decides to stop for a night in the Bates Motel. She redeems herself to the audience by deciding to go back and return the money she stole. However, before she can do so decides to indulge in a showerwashing away her cares and sin. Well, for a while, anyway. Alas, a dark figure enters the room and stabs her to death. The stolen money that brought the viewer to this point is merely a McGuffin (something introduced in a film to put the plot in motion but really has no importance in the film as a whole) and the focus shifts towards solving the murder mystery the audience thinks is pretty straightforward.

The perceived main character is killed thirty minutes into the movie! That type of thing did not happen in films back then nor is it especially common now. However, here’s the true brilliance of this development in the film: it leaves the audience with only one character with which to identify: the quirky, off-kilter Norman Bates. The audience first meets him when Marion arrives at the Bates Motel. Anthony Perkins, in his career-defining performance (for better or worse), plays Norman as someone who seems awkward but endearing. It’s only later, when we see him watching Marion through a hole in her hotel room wall that we suspect a certain sinister shading to the character. Much of the reason we don’t feel entirely threatened by Norman Bates, despite the fact the film offers clues that he may be at least slightly disturbed, is his demeanor and appearance. Perkins, best known for boy-next-door roles, seems so nonthreatening He is tall but thin, delicate, almost feminine, and seems as birdlike as Norman’s taxidermy subjects.

Who’s the real predator here? You’ll never guess.

His stuttering, stumbling, giggly line delivery seems odd, but not disturbingly so. As an audience, we find him off-center, but we do not perceive him as a threat.

Kinda hard to see how we missed that, huh?

When he finds Marion’s’ body, he believes (as does the audience) that his mother is responsible for the crime.

“This will not get me a favorable review on Tripadvisor, will it?”

After all, he’s already told us she “goes a little mad sometimes.” (The fact that he follows that line with, “we all go a little mad sometimes” is a clue the audience doesn’t realize is a clue until the film’s closing moments.) He cleans up the blood, wraps the body, puts it in the trunk of Marion’s car, and pushes the car into a swamp. There’s a brilliant moment in the scene in which Norman watches in horror as the car sinks and stops sinking for a few seconds.

This is the face the audience is making too.

As audience, we feel the same horror. Our first thought is, “Oh, no. He’s going to get caught.” The car then begins sinking again and disappears beneath the water’s surface, and the audience breathes a sigh of relief. In that moment, Hitchcock has the audience right where he wants them. He knows he has the viewer sympathizing with someone who, at the very least, is committing a crime, and he exploits that sympathy with a brilliant bit of manipulative, dark comedy.

Norman’s power to continually fascinate into the present might be related more to brand/name recognition than anything else, as Psycho and its various lesser sequels have earned Norman Bates a presence in the popular consciousness among many other slasher villains of film history. However,in the year of the character’s creation he embedded himself in the long memories of film viewers as the guy for which you kicked yourself for empathizing.

Psycho is not a flawless film. After all, the psychiatrist’s summation of the Norman-Norma relationship near the film’s end feels completely unnecessary. It’s an explanation where none is required. However, it has the power to put the audience on the side of an odd, young man who thought all he could do was work to protect his mother. It’s a brilliant series of events that unfolds for an audience who has no idea just how manipulated they are allowing themselves to be.

Psycho is available to purchase on DVD and Blu-Ray, as well as through streaming services, such as Amazon and Vudu.

So, what do you think? Do you think Psycho is a film that still has the power to enthrall an audience? is there another scene you feel works better? Do think the film’s overrated? Let us know in the comments.