Piltdown superman has recently promoted Answers in Genesis’ 6,000 word diatribe against my post criticising their depiction of the famous Lucy specimen. This persuaded me to get my act together and finish my series of counter-responses, so here we are once again for part 3. For those of you just joining us, we’ve previously discussed the introduction of AiG’s piece and their claim Lucy’s foramen magnum was apelike; a section in which they omitted key information concerning the AL 288-1 skull and convinently forget to bring up the DIK 1-1 skull at all. Today we’re dealing with their claims regarding Lucy’s lumbar lordosis.

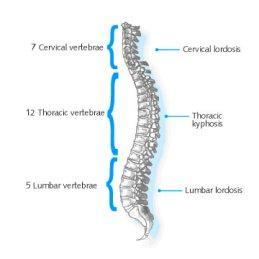

The human spine

Lumbar lordosis refers to the way our lower back curves inwards. This allows our hips to support our body by aligning it over them, also keeping the body stable. As such it’s a fairly key trait for habitual bipedalism; a trait I argued Lucy and her ilk possessed given that she has the additional lumbar vertebrae needed for lumbar lordosis and they show evidence of such curvature! Further, lumbar lordosis appears to be influenced by behaviour, not being innate but developing because humans walk upright. As such it’s presence is fairly definitive evidence that Australopithecus afarensis did spend a good chunk of time walking on two legs.

AiG’s raises 3 counter points to this claim: (1) that gorillas have been known to develop lumbar lordosis despite not being habitually bipedal, raising doubts about the link between the two; (2) having a high number of lumbar vertebrae does not necessarily result in lumbar lordosis, so the fact Lucy had more than a chimp shows nothing and (3) Lucy didn’t have more lumbar vertebrae anyways. Let’s take them in order

…gorillas have been known to develop a lumbar curve as a result of efforts at walking upright even though they are not habitually bipedal.15 And such a lumbar curve would not be passed on to offspring.

Their citation is to an article from 1889, not 1890 as AiG claim, thus rendering their whole argument flawed! Just joking, that would be a fallacious reason for rejecting this claim, although there are some decent reasons why you should be skeptical. Mostly because it’s the skeleton of a juvenile gorilla and they tend to walk upright very often; up to 1/3 of the time in some cases. Given that lumbar lordosis appears to develop in response to bipedalism, it should come as no surprise that juvenile gorllias possess it to an extent.

However, as the individual matures and grows larger bipedalism is no longer an efficient way to travel and they almost always knuckle walk instead. As a result of this their anatomy changes again, meaning that subsequent studies of lumbar lordosis in adult gorillas have failed to find it. Other flaws with the study include the fact that they didn’t actually measure the lordosis, merely an approximation of it, and the cadaver itself had already been dissected by someone else when the researcher got their hands on it.

I could go on, but I think I’ve already said enough. We can’t vindicate the reliability of this study and even if we could it wouldn’t be relevant to the discussion of Lucy.

…an abundance of lumbar vertebrae does not equate to having a lumbar curve; some gibbons have six16 and Old World monkeys can have seven,17 yet they do not ordinarily have human-like lumbar curves.

Here they’re arguing against a strawman since I never actually claimed that additional verebtrae resulted in a lumbar curve. Rather, I argued that the additional vertebrae enabled the development of a lordotic curve. You could have them and not develop it, but that’s not the point. However, I may still be wrong given that the aforementioned research into gorillas suggests lumbar lordosis could develop in an ape with fewer lumbar vertebrae.

That said, the study is rather dubious and there is the degree of scale: additional lumbar vertebrae may be required for the more extreme lordosis observed in humans, for example. Nonetheless, I hold my hands open and admit I could very well be wrong when I wrote that the additonal lumbar vertebrae in Au. afarensis is evidence of their lordosis. Of course, the upshot of this is that if Lucy had fewer lumbar vertebrae than is typically believed (as AiG attempt to argue in point 3) then that doesn’t prohibit them from developing human like curvature. Either way, AiG looses.

But did they have fewer lumbar vertebrae than once thought? The traditional model is that they had 6 and humans have since lost one and that does seem to be wrong. No handwaving or goalpost moving, I’ll concede this point completely to AiG: Lucy had 5 lumbar vertebrae. Of course, this is still more than the apes and so my original contention – that they have the additional vertebrae needed for lordosis – still stands even if I was ultimately mistaken on quite how many vertebrae there were.

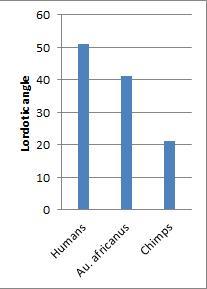

Lordotic angle of some species key to this discussion

So we know that the Australopithecines had a spine capable of lordosis but that doesn’t mean it did actually have a curve. However, people have examined the lumbar vertebrae of as many Australopithecines as possible and found that they all had a lordotic curve. Whilst few lumbar verebrae of Au. afarensis have been found I don’t think its unreasonable to conclude they also had a curve when all their close relatives did.

So there you have it, lordosis is linked to bipedalism (juvenile gorillas not refuting this) and Lucy had a spine capable of lordosis (albeit with one fewer vertebrae than I originally thought). Further, examples of Lucy’s close relatives show that they did actually have a lordotic curve, demonstrating they were terrestrial bipeds. Thus I think my original claim is still well substantiated.

Nonetheless, this is probably the best bit of AiG’s piece I’ve encountered yet. They make some decent arguments – as my number of “I could be wrong” indicates – which provide a good overview of the evidence. Aside from the irrelevant (and dubious) century old gorilla study it’s all pretty good. So why do I still think I’m right? Although they make good points they never drive the argument home and make a case for why Lucy didn’t have lordosis. They try and cast some doubts on the evidence for it (and hopefully I’ve show why those doubts are unfounded) but never manage to defeat the claim.