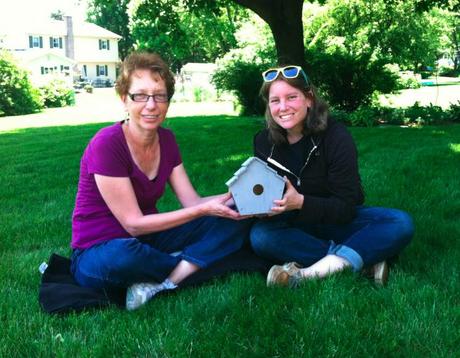

Credit: Libby Segal

I came out to my family at 25 years old. It was 2014, and while the country had made great progress in acceptance in terms of recognizing civil unions, putting more LGBTQ figures on television, and passing pro-gay laws, coming out was still a weighty experience. I was fortunate enough to have recently moved to New York, where there was less stigma and more acceptance for LGBTQ folks than there was on my college campus in Rhode Island or in my hometown of Bethlehem, PA. But even so, I struggled with the coming out process, mostly because I had struggled so hard to come out to myself.

I had never really been worried about what my parents would say or think when I eventually came out, but I waited a while nonetheless. I had always just wanted to be “sure” before I told them. So I carefully planned how I would tell my family – well, at least how I would tell my mom. I had planned to go to the mall with my mother over Easter weekend, and decided I would tell her on the drive back to my childhood home.

But the morning of “the plan,” I woke up and felt a sharp pain in my gut. I was worried. A whirlwind of new questions began to cross my mind: What if coming out to my family did change our relationship; what if my family did care? What if they even disowned me? I hadn’t actually asked myself any of these questions before that moment, and the fear of losing my family became a truly imminent one. I didn’t want my family to hate me and began to second-guess if coming out was what I truly wanted to do.

I forced myself to get in the car with my mom that day and drive to the mall as I had planned we would. We walked to our favorite stores, indulging the latest fashions, and sneering at the clothing neither of us would dare to don. We ran into an old high school friend of mine and contemplated stopping for lunch or grabbing coffee. For my mother, this was just another “mother-daughter outing.” But the entire day – my actual “outing” – felt different to me. As we made our way up and down the sidewalks of the Promenade, I could hear my thoughts keeping pac with the rhythm of my steps. On the exterior, I was holding myself together, but a tug of war match between “tell her,” and “wait, don’t tell her” echoed loudly within my core.

After hitting our last store, we walked back to the car. I walked a little bit more slowly than usual, thinking, “this is it.” I considered deciding not to come out, to accept that I might not be ready. But I knew that I wanted to get the weight of being in the closet off my shoulders. I knew I needed to come out for many reasons: I wanted to be able to have honest conversations with my mom. I wanted to stop worrying about what pronoun might come out of my mouth when I talked about who I was dating or who I had my most recent crush on, and I wanted to be able to fully be myself.

But beyond the “me” piece of the puzzle, there was always the “other” piece of the puzzle. I wanted to be sure that my family was open and accepting before I brought any significant other home in the future. I knew friends who had come out to their family with a significant other, and had read about others’ turbulent experiences. But I also knew, especially if things did go sour, that I didn’t want anyone to associate my experience of coming out with anything other than myself.

My mother got in the passenger seat; I got into the driver’s seat. We buckled up and I put the gear in drive. As we left the parking lot. I could feel my insides tangling. I had planned to come out right then and there, but hadn’t written a script. I had no idea what was going to come out of my mouth, but took a deep breath and turned to my mother. Her window was open and she was smoking a cigarette.

“Mom.”

There was a pause.

“Lib.”

Another sustained pause.

“I have a question.”

I paused once more.

“Could you ever hate me?”

I watched as she took a puff of her cigarette. She pondered the question.

“Hmm. I guess if you ever committed grand larceny, or killed someone,” she said, laughing a little.

As silence fell over the car, I could tell my mother was confused. I was clearly nervous: my hands were shaking on the steering wheel.

“Libby, what the hell did you do?” She snapped.

Her voice was loud, although she rarely raises it with me.

“I don’t think we are on the same page,” I calmly responded before taking another deep breath.

“I was just going to tell you that I might be dating women; and by might be, I mean. I am.”

My body became perfectly still, as did the car as we had reached the next red light. I looked over at my mom again. She took another puff of her cigarette, and looked out the window, before turning to me and saying: “Okay. How about we go get that ice cream we talked about getting.”

That was it. No questions asked. I asked her to tell my dad, and in the months that followed, I would find the strength to tell my brother and my sister. My siblings reacted positively, telling me they were proud of me and happy that I felt as though I could be myself with them. My father and I never directly spoke about it, though nothing about our relationship changed. Then months later, on my “Facebook coming out post,” he wrote one simple comment: “Great Post, Lib.” It was the only comment he’d ever written on Facebook.

Over the next year or so, I would often come home and find a book that my mom had pulled off the shelf for me related to gay culture. We didn’t talk about it out loud, but the gesture was enough to show me that she heard me, she wasn’t ignoring the conversation we once had, or what felt to me like a monumental moment in my life. As far as I could tell she accepted what I had told her, even if her way of doing so was through small gestures.

On New Year’s Day, this year, I called my mom to wish her a Happy New Year and to ask her how she had spent her night. It turns out it was a simple night for her: She told me she had brought in the New Year on the couch with my dad, our cat, and my grandmother, who sat nearby on a reclining chair.

“What a sweet night: you, your husband, and your mom bringing in the new-year together,” I remarked.

“One day it’ll be you,” she began. “You, and your wife, and your mom bringing in the new-year together.”