They're everywhere. Like a crude oil spill in the Gulf, vegetable oils - those slippery, modern elixirs - have seeped their way into all the nooks and crannies of our food supply.

If you eat out, chances are your food is cooked in - or doused with - some type of vegetable oil. If you buy packaged goods like crackers, chips or cookies, take a look for it on the label; there's a very good chance that vegetable oils have oozed their way in. If you buy spreads, dips, dressings, margarine, shortening or mayo, can you guess the star ingredient? Yup - vegetable oils.

Vegetable oils have quickly become a major source of calories in our food supply. Is that a good thing? To find out, let's review what we know, and what we don't know, about these pale and innocent-looking plant-based fats. As you will see, we have a pretty good handle on the basics, but, beyond that, there is a lack of evidence and scientific consensus about the healthfulness of these glistening food science darlings.

Ready for a deep dive into the slick, new man-made fats in our diets? Click any of the links to jump to that section, or simply keep reading!

Let's start with the basics. We actually know a lot about the origins of vegetable oils and their chemical makeup.

What are vegetable oils?

In a technical sense, vegetable oils include all fats from plants. However, in common usage, "vegetable oil" refers to the oil extracted from crops like soy, canola (rapeseed), corn and cotton.

Is olive oil a vegetable oil? What about palm oil and coconut oil? Technically yes, these oils come from plants, so they are vegetable oils. But they originate from the fruit or nut rather than the seed and are easier to extract. These oils have been a part of the food supply for thousands of years. Together, these three traditional oils account for less than 15% of today's vegetable oil consumption in the US. More than half - about 53% - of the vegetable oils consumed in the US comes from just one crop: soybeans.

For purposes of this post, we will narrow the meaning of vegetable oils to include only oils from the industrial oilseed crops: soybean, canola (rapeseed), corn, sunflower, cottonseed and safflower oils.

In addition, we will assume the vegetable oils we are discussing have NOT been hydrogenated. Hydrogenated vegetable oil products, like Crisco and margarine, were once marketed to Americans as "heart healthy." Now we call these hydrogenated vegetable oils "trans fats," and because of their negative effect on health, we are in the process of eliminating them from our food supply.

How are vegetable oils made?

Unlike olive oil that has been pressed for centuries, vegetable oils require industrial processing. They are extracted from oilseed crops in large factories. Seeds are crushed or flaked, but that is just the beginning of the industrial processing required to generate the pale, mild-tasting oils that end up in your salad dressing.

Heat, cold, high-speed spinning, solvents (like hexane - derived from crude oil), degumming agents, deodorizers and bleaching agents are all necessary to process the seeds into a palatable oil.

For a visual rendition of this industrial process, check out this video that documents the production of canola oil.

Make no mistake: Modern vegetable oils are the ultra-processed products of food science laboratories and factories.

How much vegetable oil are we eating?

Refined vegetable oils are the 'new kid on the block' in human diets. They didn't exist 100 years ago, so we certainly weren't eating them then. Yet, by 2014, the average American was consuming about 50 g, or 11 teaspoons of vegetable oils each day. That's 450 calories, or about 20% of a 2,250 calorie diet. This is roughly double the amount consumed in 1970. No other source of calories has contributed as much to America's caloric intake increase between 1970 and 2014.

Our modern appetite for vegetable oils signifies a real change in a meaningful share of our national diet.

What types of fatty acids are in vegetable oils?

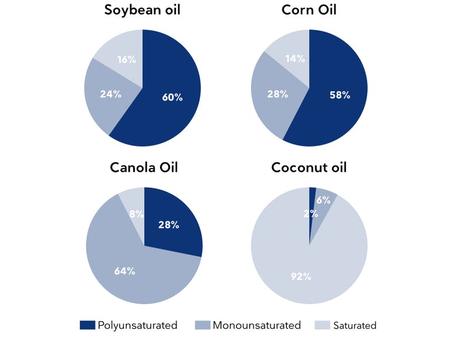

All fats contain a blend of saturated (SFA), monounsaturated (MUFA) and polyunsaturated (PUFA) fatty acids ( learn more), and vegetable oils are no exception. Each type of seed has its own signature blend of the dozens of possible fatty acids that occur in nature, and each fatty acid is either a saturated, monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fatty acid.

Take a look at the percentage makeup of each of the three main vegetable oils in our food supply, compared to coconut oil, a traditional plant fat:

For more on the origin and structure of different types of fat, check out our guide below.

What about omega-6?

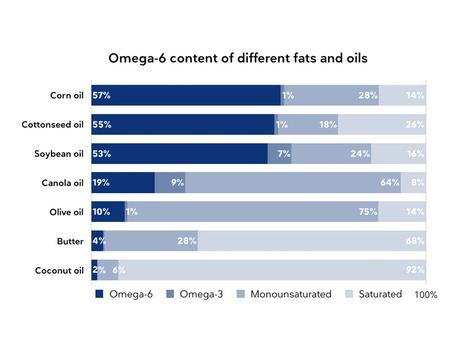

Most vegetable oils contain high levels of omega-6 fatty acids. There are exceptions (like high-oleic canola oil), but vegetable oil varieties like soy, corn, cottonseed, safflower and sunflower all contribute to the abundance of omega-6 fatty acids (over omega-3 fatty acids) in the standard American diet.

This is a decidedly modern pattern; traditional diets were never high in omega-6 fatty acids. A high ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 is often linked to inflammation and chronic disease.

What happens when we cook with vegetable oils?

Vegetable oils contain mostly polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, which means they are liquid at room temperature. It also means that they are innately less stable than a predominately saturated fat. This is because unsaturated fatty acids have one or more unsaturated (double) chemical bonds that react more easily than the stable single bonds in a fully saturated fatty acid.

Even if vegetable oils can be stabilized during production to achieve a reasonable shelf life, adding heat can quickly oxidize them.

As Nina Teicholz notes in her talk, " The unknown story of vegetable oils," and in her bestselling book, The Big Fat Surprise, putting vegetable oils into deep fryers creates an oxidized, gummy mess. It is hard to predict how our bodies manage these already oxidized, unstable fatty acids once ingested.

Fats that include higher levels of saturated fatty acids, like clarified butter and coconut oil, are the most heat-stable fats, and are much safer for cooking.

These mostly saturated fats are solid at room temperature, do not become rancid when stored, and resist oxidization when heated. Lard and extra virgin olive oil, both made up of predominately monounsaturated fatty acids, are also quite heat stable.

What happens to the vegetable oils that we eat?

Fatty acids can be burned for energy, so vegetable oils are a source of fuel. If we do not need that energy immediately, our bodies store it in our fat cells. But fatty acids are also used to build and repair body parts and create signaling molecules (like eicosanoids), so the vegetable oils you eat literally become a part of you. Your mother was right - you really are what you eat!

Your body needs to incorporate fatty acids into a variety of structures, particularly cell membranes. And the selection of fatty acids in the food you eat provides the array of building blocks available to the body. Your body can rearrange some of these fatty acids, and make a somewhat different mix to suit its needs. But the raw materials provided by vegetable oils are not identical to the building blocks that a diet containing more traditional fats provides. As a result, we end up with less stable fatty acids incorporated into our cell membranes, which affects membrane fluidity and cellular function.

This begs the question: Does a diet high in vegetable oils change our bodies in a healthy way? We don't know. What a perfect segue into the next section of this guide...

To recap, we know that vegetable oils:

- Come from seeds.

- Are (relatively) new.

- Are heavily refined.

- Are a mixture of polyunsaturated, monounsaturated and saturated fats, and most are rich in polyunsaturated fats.

- Are an unnaturally rich source of omega-6 fatty acids.

- Are unstable, especially when heated.

- End up in our bodies, particularly in our fat stores and cell membranes.

These are big red flags. It is hard to imagine that ultimately these shaky credentials magically combine to make modern vegetable oils an elixir of health. That said, what we don't really know is the answer to the most fundamental question: Are vegetable oils good for us to eat?

More specifically:

Are vegetable oils "heart healthy"?

We have been asked by public health officials to move away from saturated fats toward polyunsaturated fats, always with the promise of better heart health. We have complied, and eaten less butter and more vegetable oils. But is there clear, clinical evidence that substituting polyunsaturated fats for saturated fats improves heart health?

Meta-analyses of epidemiological data are mixed, but typically demonstrate that people who eat more polyunsaturated fat and less saturated fat have fewer heart events.

Although interesting, this is a weak statistical correlation, and any scientist knows that this does not demonstrate cause. Oddly, the enduring insistence that vegetable oils are superior and "heart healthy," from influential institutions like the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, is largely based on these weak observational associations. Relying on small hazard ratios (anything below 2.0) from epidemiological data to infer causation is bad science. (If you are not familiar with the problems with inferring causation from observational studies, this classic post from science journalist Gary Taubes lays out a detailed critique.)

We should look for better evidence, from carefully designed clinical trials, before welcoming vegetable oils into our food supply. Fortunately, there are several meta-analyses that pool the evidence from randomized clinical trials, which is the best quality of evidence. Some meta-analysis conclude vegetable oils modestly reduce cardiovascular disease risk, but the effect is small.On the other hand, several meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials find no link whatsoever between vegetable oils and death due to heart disease.

Here is an example of how the researchers who do link vegetable oils to heart events characterize their modest findings. This excerpt is from the very latest (July 2018) Cochrane Review of RCTs, entitled " Polyunsaturated fatty acids for prevention and treatment of diseases of the heart and circulation ":

"Increasing PUFA [PolyUnsaturated Fatty Acids] probably makes little or no difference (neither benefit nor harm) to our risk of death (moderate-quality evidence), and may make little or no difference to our risk of dying from cardiovascular disease (low-quality evidence). However, increasing PUFA probably slightly reduces our risk of heart disease events and of combined heart and stroke events (moderate-quality evidence). Fifty three people would need to eat more PUFA to prevent one person experiencing a heart disease event, and 63 people to prevent one person experiencing a heart or stroke event. Increasing PUFA may very slightly reduce risk of death due to heart disease, as well as stroke, but harm is possible (low-quality evidence). PUFA probably slightly reduces fats circulating in the blood (cholesterol, high-quality evidence and triglycerides, moderate-quality evidence). Increasing PUFA probably slightly increases body weight (moderate-quality evidence). The evidence mainly comes from trials of men living in high-income countries."

How can this be? How can different meta-analyses come up with different answers? It all depends upon which underlying clinical trials the authors of the meta-analysis include. And this can be influenced by point of view.

Gary Taubes writes about this problem with the science in a blog post entitled Vegetable oils, (Francis) Bacon, Bing Crosby, and the American Heart Association:

"A Scottish cardiologist/epidemiologist described this pseudoscientific methodology to me as "Bing Crosby epidemiology" - i.e., "accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative." In short, it's cherry picking, and it's how a lawyer builds an argument but not how a scientist works to establish reliable knowledge..."

When we look at the underlying randomized clinical trials included in these meta-analyses, we see that several of them (like the Minnesota Coronary Experiment and the Sydney Diet Heart Study) show that diets higher in vegetable oils and lower in saturated fat do indeed lower total blood cholesterol, yet the lower cholesterol level does not improve mortality rates. In fact, in these two trials, the opposite is true. That's right. These trials document HIGHER risk of death among the intervention group, in spite of the subjects' lower blood cholesterol levels.

Perhaps herein lies part of the confusion surrounding vegetable oils. The American Heart Association (AHA) bases its endorsements of vegetable oils on the purported link between lower LDL cholesterol levels and better heart health. But these carefully executed clinical trials do not support that final step. Do vegetable oils lower LDL cholesterol? Yes. Does that improve hard endpoints like all cause mortality or cardiovascular disease mortality? These trials' answer is "no." If vegetable oils are truly good for our heart health, why aren't the randomized clinical trials more consistently showing less mortality (and hence, longer lives) among the subjects ingesting them?

Some scientists and doctors think that the unstable, easily oxidized polyunsaturated fatty acids in vegetable oils are part of the reason vegetable oils are a problem, not a solution. In a recent review paper published in Open Heart, authors DiNicolantonio and O'Keefe make the case for what they call the "oxidized linoleic acid hypothesis." Their contrarian paper explains the mechanism through which omega-6 vegetable oils might drive not less, but more coronary heart disease. After reviewing the evidence, they conclude:

"In summary, numerous lines of evidence show that the omega-6 polyunsaturated fat linoleic acid promotes oxidative stress, oxidized LDL, chronic low-grade inflammation and atherosclerosis, and is likely a major dietary culprit for causing CHD, especially when consumed in the form of industrial seed oils commonly referred to as 'vegetable oils'."

What's the bottom line? The science is still inconclusive.

The lack of compelling and consistent clinical trial evidence proving that vegetable oils deliver meaningfully better heart health is astonishing, and evidence showing the opposite is mounting. About fifty years ago, these new man-made oils gained easy entry into our food supply based on weak evidence and false promises. Is it possible that vegetable oils slightly reduce heart events? Yes, but it is far from certain - the evidence is mixed. Further, what we really care about is all cause mortality and healthspan. How do vegetable oils affect longevity and wellness?

Do vegetable oils increase cancer risk?

As we struggle to understand cancer risk, diet is often identified as a key driver. But studies are all over the map. One observational trial (and the splashy headlines that follow) shows a particular food is protective; the next trial of the same food shows the opposite effect.

There are many observational studies showing associations between high omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid consumption and cancer. But again, this is observational data; we cannot assume causation from this weak evidence.

There have long been animal studies showing that vegetable oils contribute to tumor growth. And there has long been concern that this might be happening in humans.

But ultimately, we must look to well-designed clinical trials (in humans) for answers. There is little of this rigorous science available. An older trial, conducted in a Los Angeles Veterans' home in the late 60s, revealed a large escalation of cancer mortality among men eating the experimental diet that was heavy in vegetable oils. (This trial also showed lower CVD mortality for those replacing dairy fats with vegetable oils.) But there were problems with the study, such as more heavy smokers in the control group, and subjects eating many meals away from the controlled institutional setting. We simply need more data to carefully evaluate vegetable oils and cancer risk.

At this point, we don't really know if vegetable oils contribute to escalating cancer incidence.

Do vegetable oils affect mental health?

Some have suggested that omega-6-heavy vegetable oils contribute to ADHD and depression. Psychiatrist Georgia Ede writes about this potential link, and the mechanisms she believes are behind it, on her website. But until clinical trials are completed, we just don't know whether or not vegetable oils contribute to the escalating rates of anxiety, attention disorders, and depression in recent decades.

Are vegetable oils contributing to the obesity and diabetes epidemics?

The rise of obesity and diabetes that we have seen over the last 40 years has been matched by an equally dramatic increase in vegetable oil consumption. Is there a connection, or is this just a coincidence?

Animal studies are numerous and mixed. But in humans, the science is scant. Setting aside observational studies (very weak evidence) suggesting an association ( like this one), there is a Cochrane review of clinical trials that concludes that vegetable oils contribute to a slight (less than 1 kg or about 2 pounds) increase in mean body weight; the difference in mean body weight was higher (2.37 kg or about 5 pounds) when the study design simply gave advice to consume more polyunsaturated fats. Although this finding was significant, it is too early to conclude that vegetable oils are uniquely fattening. And the question of a causal link between vegetable oils and diabetes has yet to be carefully explored.

Bottom line: We don't know if vegetable oils are causing obesity and diabetes.

Our top sauce and dressing recipesIf you are troubled - as we are - by what we know about vegetable oils, and what we don't know, the safest course is to avoid these newcomers as much as possible and return to traditional dietary fat sources. Get your fats from whole foods, traditional oils and, of course, butter.

Five step action plan: How to eat less vegetable oil

Here are five steps to help you reduce the vegetable oils in your diet:

- Stop buying them. The most obvious step is easy - stop buying them! Substitute a different fat for frying, baking and dressing. Try one of these: butter (or ghee), sour cream, lard, tallow, schmaltz, extra-virgin olive oil, cold-pressed coconut oil, and extra-virgin red palm oils. Why not check out our delicious guide dedicated to eating more healthy fat!

- Make your own dressing. Remember that almost all of the pre-made salad dressings in the grocery store are laced with vegetable oils. So it's time to start making your own! Boy, do we have some quick and easy recipes (see above, too)!

- Buy or make better mayonnaise. Unfortunately, most popular brands of mayo are 100% soybean oil. You can buy specialty products made with avocado oil instead, and there is nothing like homemade mayo!

- Substitute with quality oils when eating out. When you eat out, ask for olive oil and vinegar for your salad. (Some people even like to pack their own favorite dressing.) Another trick at restaurants is asking the waiter if the chef could fry your food in butter or coconut oil instead of the standard cooking oil. Not all establishments can accommodate this request, but it's worth a try!

- Cut out baked goods and snacks. There are lots of reasons (hello, sugar and refined grains) to avoid commercial baked goods and snacks, and now you have one more reason - they usually contain vegetable oils. Most bakery-made or packaged cookies, pastries, cakes, breads, crackers, chips and bars are made with vegetable oils. Check out the ingredients list before you buy.

Are you still confused about vegetable oils? Science definitely doesn't have all the answers. Our advice? When in doubt, stick with foods that have been around for thousands of years.

/ Jennifer Calihan