Intermixed with much of the worst of human history is a religious motivation. This can be seen in the involvement of a religious motivation in the genocide committed against American Indians and the Holocaust. More recently, this can be seen in the motivation behind tragedies such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the January 6 attack on the United States Capital. Other examples include the involvement of religion in motivating slavery across the world, prejudice and violence directed toward members of the LGBTQ population, and various cases of religious persecution.

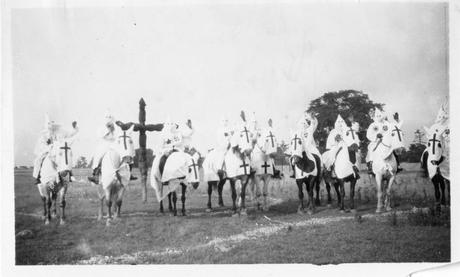

Hooded Members of the Ku Klux Klan Displaying Christian Imagery, 1935.

Hooded Members of the Ku Klux Klan Displaying Christian Imagery, 1935.

As Blaise Pascal once reflected: “human beings never do evil so completely and so joyously as when they do it from a religious motivation.”

How can great world religions – which generally teach love, compassion, and justice – become powerful instruments of prejudice and violence?

Although acts of religiously-inspired hatred are complex and caused by many variables, one common factor concerns religious fundamentalism.

Religious fundamentalism involves a rigid kind of certainty in the possession of the “one truth” and the “one way” to live. It typically relies on a literal interpretation of a sacred text and an absolute reliance on that text. Other sources of knowing what’s true or other ways of determining what’s valuable are rejected – such as when science or a different group offers an alternative perspective – in favor of what’s unquestioningly accepted within the group.

With this all comes a strong urge for fundamentalists to form a sense of who are “insiders” and who are “outsiders.” Explicitly or implicitly, it’s easy for all of us to believe members of our groups are superior, while others are inferior. One way for religious fundamentalists to address this is to develop an evangelical zeal to bring outsiders to the inside through attempts to convert them. However, when individuals reject their arguments or invitations, fundamentalists can develop even stronger attitudes against them, to the point where outsiders can become seen as less than their human equals, sometimes even leading to consciously or unconsciously dehumanizing them. At this point, prejudice and violence toward members of the outgroup become more likely.

Because fundamentalist groups also tend to draw like-minded people to their communities, individuals in these groups often decrease or completely lose contact with those different from themselves. As a result, the kinds of reality checks most people tend to naturally have happen to them when they interact with people different from them become less likely, creating the conditions for stronger stereotypes and prejudices to develop.

Sometimes, the content of what gets taught in a fundamentalist group also plays a role in promoting religious aggression. Consistent with this, in one study, research participants who were told that a passage condoning violence came from the Bible were more likely to be violent in a lab activity that followed, compared with those who were told it came from an ancient scroll. In a follow-up study, individuals told that the passage was sanctioned by God were more violent than those who had that information withheld. The researchers speculated that, “to the extent that religious extremists engage in prolonged, selective reading of the scriptures, focusing on violent retribution toward unbelievers instead of the overall message of acceptance and understanding, one might expect to see increased brutality.”

In response to this, many people in the developed world are withdrawing from religion. None of us want to affiliate with groups or movements that make the world a worse place.

But, what if the cure to religiously-inspired hatred wasn’t less religion, but better religion? As the great psychologist of religion, Gordon Allport, said, “there is something about religion that makes prejudice, and something that unmakes it.” What does a religion of peace look like?

It’s important we recognize there are strong psychological needs that fundamentalist groups meet – including needs for meaning, worth, and community – and to conceive of ways for religions to meet these needs in ways that foster inclusion and relationships across groups characterized by respect. For example, religions can draw deeply from their sacred texts, histories, and traditions to create high-demand groups focusing on humility, compassion, and justice. As part of this, religious groups can seek to understand their diverse neighbors through interfaith dialogue, friendship, and work requiring the resources of all to address a common problem and to advance the common good. As religious groups engage in this work, they can form tight communities that need not feel they are superior to others while at the same time encouraging a strong sense of shared identity and purpose.

In this, we individuals can ask ourselves whether belonging to our religious groups distance us from others or help us to connect with, work with, and befriend others. If we recognize that our groups are making it harder for us to empathize with others, we might consider how we might push for or lead a change, or leave a group altogether for something better. After all, it’s possible to use the many resources of our faith communities to bring curiosity, wonderment, and reverence to those different from us – as fellow humans, with sacred worth – while at the same time exploring our own identities and communities.

As the theologian Miroslav Volf said: “it may not be too much to claim that the future of the world will depend on how we deal with identity and difference.”