I could go on and on.

We’re in mysterious terrain. The paradox that is Tarantino’s career most closely resembles the “so-bad-it’s-good” paradox—but that’s not it.

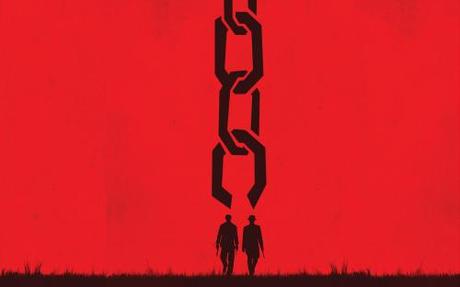

If it’s working, Django is an examination of history from fantasy. If it’s not, it’s fantasy-pleasure scraped out of historical pain. The latter is amoral at best, immoral at worst. The former is highly moral. Both are self-aware.

And in that department: I don’t know what it is.

Structurally it’s a mess. An odyssey full of bits and segments and detours where the scramble for pleasurable-payoff is often so transparent, so easy, that it’s hard to just let yourself enjoy. The ride keeps stopping. That’s what makes it minor Tarantino.

And then there’s Candy Land. Once Tarantino finds his screenplay firmly rooted to Candy Land, everything gets much, much better. He seems to work best given restraints (unsurprising) and the natural physical crucible provided by the plantation space do his story a lot of favors. Suddenly we know where we are. We know the characters, the rules (sort of) and the stakes. For the sake of spoilers (Tarantino’s work is holy) I’ll only say here that the game does sort of collapse at the end. Perhaps the heroes aren’t smart enough, or good enough at doing their jobs?

Rather than mire in the details, I’ll say the movie works as: a vital injection of style into a commercial wasteland. It’s fun, brutal, and intriguingly historical (really.)

Watching American history get reprocessed as pop continues to be funny and eerie at the same time. How many times did you think about Abraham Lincoln between elementary school and when Spielberg’s “epic” came out?

I’m not accusing you, Dear Reader, just saying that this is where the dreams, the history, the ancestry, is getting stashed: Hollywood.

In a particularly bad Terry Gross interview, Terry asks if it was awkward shooting black people pretending to be slaves. Tarantino mentions, with admirable restraint, that they’re all breaking for Powerbars in between cotton pickin’ sessions and that “everyone knows what time it is.” I love the question, because it points to the fact that we still believe movies are real, even when we know they’re not.

Surprise has been registered (and more frequently, can be inferred) from some corners that a white man is making a film about a black slave killing white Americans. But it’s not surprising. Django is kind of sweet in that way. A lot more innocent when you realize it’s an awkward, fumbling scream from the white-guilt-ridden subconscious of one American, who only knows how to rip apart history and morals from a genre-film perspective. And in the end, that’s what makes the Tarantino “style over substance” debate so absurd. It’s like the complaint that Hemingway’s sentences aren’t long enough, or his words big enough, to tell the important stories.

-Max Berwald