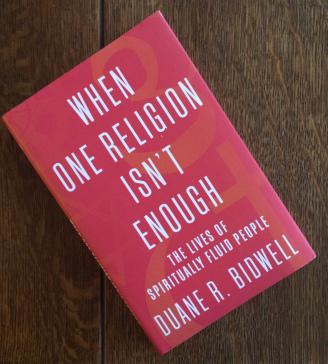

It brings me great joy to celebrate the recent publication of When One Religion Isn't Enough: The Lives of Spiritually Fluid People, by Duane Bidwell, who is a Buddhist, a Christian minister, and a scholar at the Claremont School of Theology. If you follow this blog, you will want to read this book.

Note: I am not the least bit objective about Bidwell's work. I count the author as a friend, discussed the ideas with him over many years, and encouraged Beacon Press to publish this book. I knew it would help create an academic foundation for our nascent field, and greater acceptance for all of us with complex religious lives. Bidwell cites my work, including reprinting the Bill of Rights for Interfaith People I adapted from Maria Root's work. And it is an honor to be quoted on the back of the book, alongside academic luminaries Paul Knitter, John Thatamanil and Peniel Jesadason Rufus Rajkumar.

Here's what I wrote:

"This groundbreaking book is essential for anyone who wants to understand the contemporary religious landscape. Bidwell offers up richly detailed personal stories told with great sensitivity. In telling these stories, this book documents spiritual fluidity as transgressive yet also life-giving, and as important and surprisingly common rather than marginal and exceptional."I think of Bidwell's book as a necessary complement to . While Being Both describes people from interfaith families celebrating more than one religion, Bidwell puts these families into a more global context in which whole cultures celebrate more than one religion, and also explains why more adults in the U.S. are intentionally taking on a second religion.

A word on terminology: part of the difficulty with establishing this field of study, and bringing together people from different worlds to discuss it, is that there is no consensus on how we describe ourselves. Some religious institutions still use self-referential language, such as " intermarriage" and "partial" identities. Catholic theologians created the term multiple religious belonging, but many have now shifted to multiple religious practice or multiple religious bonds, since the individual does not fully control where they can belong. Multifaith, interreligious, interbelief, and interworldview have all been suggested as alternatives to interfaith. Anthropologists and sociologists may use the terms syncretism, hybridity, or bricolage. And in what I call #GenInterfaith, young people are more apt to use terms like mixed, religiously non-binary or intersectional, or religiously queer.

I have stood by the use of the term "interfaith," in part because I want people to be able to find these writings, and "interfaith family" is a succinct term and still the one they are most likely to search. And while some find the many different uses of "interfaith" confusing, I am intentional in linking interfaith families and interfaith identities with interfaith peace-making and interfaith activism. And I am intentional in pushing back against those who still believe any form of "interfaith" is dangerous.

Into this complex and frankly confusing semantic landscape, Duane Bidwell makes a bold case for using the terms religious multiplicity, and spiritual fluidity. I worry that anything with"fluidity" makes us sound mercurial, when some of us feel very grounded and stable in our complexity. But I appreciate Bidwell's thoughtful parsing of the options and implications, and if we converge on these new terms, I'm certainly going along!

When One Religion is Not Enough describes how individuals come to be religiously multiple, how they navigate the world with these identities or practices, and also, how they contribute to the world. This last point will strike many who harbor lingering doubts as the most novel, and most challenging. And yet, Bidwell wisely insists, "monoreligious and multiple religious people can learn from each other."

One key contribution of this book is setting these ideas in historical and geographical context. The author refers to how spiritual fluidity arises through colonialism, conquest, appropriation, and the overlay in time and space of religious traditions. And the interviews and anecdotes draw on the rich diversity of the United States, bringing us a host of marginalized voices.

Informants include a Catholic Tibetan Buddhist, a Canadian raised with Christianity and Hinduism, a Christian theologian who grew up practicing Santeria, and a Christian pastor who is also an Ifa priest. Each of us inevitably peers through our own lenses, and Bidwell's lenses are clearly Christian and Buddhist. But one of the many strengths of this book is the acknowledgement of the importance of immigrant, indigenous, and African diaspora religious identities in this country.

Another key contribution is the way that Bidwell organizes people with complex religious bonds: those who choose complexity, those who feel called to it, and those who inherit multiplicity either from interfaith parents or multi-religious cultures. But then he gracefully concedes that disentangling such categories is not always easy or possible: "...the categories of religious choice, heritage, and invitation are not pure or exclusive."

I look forward to a lifetime of wrestling with this material, in conversation with this author. Bidwell writes, "In the end, people choose complex religious bonds because multiplicity offers them more benefits than drawbacks." This certainly affirms my conclusion in studying, and living in, interfaith families. And I am thrilled that this book places people from interfaith families in conversation with other people living religiously complex lives.

Journalist Susan Katz Miller is an interfaith families speaker, consultant, and coach, and author of Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family (2015), and The Interfaith Family Journal (forthcoming in 2019). Follow her on twitter @susankatzmiller.