Guillermo Dominguez, a portfolio manager for New River Investments, came up with a good term a few years ago for the new economy he was seeing emerge out of his quickly gentrifying neighborhood. “The Quaint Economy,” as he called it, was one where businesses sell the story of how something was made, not really the thing itself. “It’s our desire to drink cocktails out of mason jars, rather than mass produced glasses at Ikea, at a bar covered in reclaimed wood from a barn in Kentucky rather than something you’d find in the interior of a DMV.” It’s the consumer quest for all things “authentic” and “pre-modern,” conflating quality with nostalgia. The quainter the story, the better.

You see this everywhere with clothing, not just in terms of styles (e.g. old-timey workwear and three-piece suits), but also production. Even at chain stores such as J. Crew, you can buy things such as selvedge denim jeans and personally monogrammed shirts, which give the impression of hand-craftsmanship even if the items were mass-produced. A few steps up are people who are willing to pay top dollar for genuinely handmade items. A Kiton shirt, for example, can be comically expensive – upwards of $800 if you want the pleasure of wearing a handsewn placket, collar, and hem.

But is handwork actually better? What’s the point of all that handsewing?

To be sure, a lot of what’s admired today is purely about embellishment – the pick stitching along the edge of a lapel or a finely sewn Milanese buttonhole. And ironically, this work is usually best when it’s nearly invisible. As my friend RJ put it years ago, the best handwork is that which is “finest, tiniest, and tightest,” such that a well-made, hand-stitched buttonhole is nearly indistinguishable from one that’s been machine sewn (at least to the common eye). Bad buttonholes, on the other hand, are uneven and messy. British tailors call them “crushed beetles.”

No one argues about decorative topstitching, however. They are, by definition, embellishments. The usual justification for handwork is that a handsewn seam allows for more flexibility. Tailors use what’s known as a back-stitch, which is a series of overlapping, looped stitches that allow for more stretch than machine-made lock-stitches. When placed on areas of high stress – say, the seat seam on a pair of trousers or the sleeve seam on a jacket – you wind up with a more comfortable and durable garment. Where a lock-stitch might snap if stretched enough, a backstitch will hold.

Jeffery Diduch, the VP of Technical Design at Hickey Freeman, had a great post about this years ago at his blog, where he dissected a pair of Henry Poole trousers. As he puts it, this is only true if you compare back-stitches to lock-stitches, and technology has come a long way since the invention of plain sewing machines:

There are now machines which not only replicate that looping hand stitch, but better it, creating complex looping chain-stitches with one or several threads which are far more flexible and strong than any handsewn backstitch. Those machines can be expensive though, so most tailor shops will not bother with the expense of such a machine which is only good for 3 or 4 of the hundreds of operations involved in making a suit. My guess is that many of the tailors who chant the mantra of the hand stitch have never seen a lot of the equipment available today. And even though you will hear it repeated often that hand-sewn seams are superior, if you look inside what you thought was a very well-made pant and see that the seat seam has been done by some sort of machine, do not feel that you been been short-changed because the seam was not done by hand. In fact, it is likely that the seam is much stronger than a hand-sewn seam.

My sense is that the mystique around handwork exists for a few reasons. First, everyone wants it. Consumers want practical reasons for why they should pay so much more for a handsewn item, and companies are all too happy to provide them. Second, the idea is easy to remember (i.e. “handsewn seams are more flexible”), so it lives on through online forums and blogs.

The other reason is that, speaking as someone who’s been writing about menswear for a few years, has to do with how content in this space is created. If you want to talk about handmade, bespoke items, you’ll likely talk to a tailor at some point. Indeed, some tailors even run their own shops, such that you can reach them directly by calling the shop’s number. The problem is that, as Jeffery points out, they’re often only familiar with their specific trade. They can tell you how back-stitches compare to the plain sewing machines in their workshop, but won’t know about more advanced technologies because they don’t do that kind of work. Those machines are for businesses pushing out tens of thousands of garments per year – multiples larger than what a bespoke firm will make.

If you want to write about factory production, however, you’re more likely to talk to a PR rep than someone working on the factory floor. Which means, you’ll learn a lot about the company’s heritage and how they don’t offshore to China, but little about their production process beyond the superficial points. Those sort of nuances require years of education to understand anyway, so they matter little for popular press.

So, given the asymmetric distribution of information, you’ll often read on blogs about the virtues of handwork, as the writer is passing along information he heard from a bespoke tailor or brand specializing in handsewn items.

The reality is, most of the information you read about men’s clothing is for marketing purposes. That’s true whether it’s coming from a tailor’s workshop or brand’s offices. Certainly, handwork may matter for some areas of production, but it’s unlikely in a way a common consumer can easily discern. The area where it would make the most impact is in the guts of a suit, where it’s hidden from view, not along the lapel or lining. And, unfortunately, you can’t even trust salespeople or tailors these days on whether the interior was hand done. Many times, they’ll tell you whatever you want to hear. In the Quaint Economy, the story is more important than the product.

This isn’t to be cynical. I obviously like handmade, bespoke items enough to pay for them – using companies such as Steed for my suits and Nicholas Templeman for shoes. When well done, a handmade item lends a bit of romance to life. What would be the point of appreciating clothes if you just reduced them to their barest, more utilitarian purposes? Even machine-made items need a bit of symbolism to be enjoyable (e.g. the rugged Western fantasy of RRL or subtle patrician connotations of Barbour). I just think handwork should be appreciated on its own terms. There’s no need to invent practical justifications for what’s obviously a luxury.

On the other hand, if you’re only interested in the practical purpose of clothes, skip the backstory. To the degree that handwork matters, it should show in how a garment looks and feels when you wear it. You don’t need to know how much hand-stitching went into an item to judge whether it makes you look good. Most of the time, those stories obscure more practical judgements.

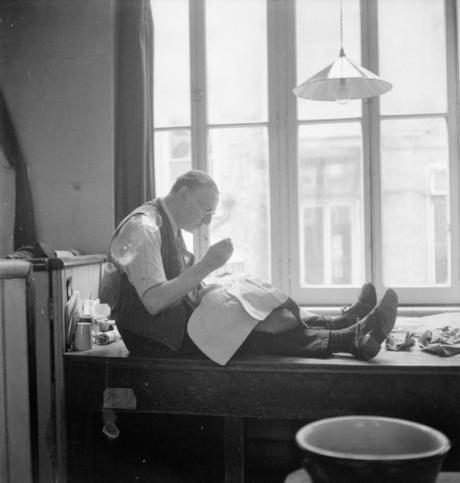

(photos of Henry Poole’s workshop, via Wikipedia)