It's often said that America has not been this divided since the Civil War, but even these tumultuous times pale in comparison to the social unrest of the 1960s, when post-war America's cleavages along race, gender, and sexuality threatened to rip the nation apart. Within ten short years, the United States saw the unfolding of the civil rights movement and the outbreak of countless race riots; the publishing of Betty Friedan's 1963 book The Feminine Mystique, which sparked second-wave feminism; the Vietnam War and anti-war protests; countless acts of state violence, such as the My Lai Massacre and police brutality at the 1968 DNC; and three major political assassinations (JFK in '63, Malcolm X in '65, and Martin Luther King Jr. in '68). The one bright spot came at the end of this dark decade, when the world finally saw a brighter facet of the American spirit.

In the summer of 1969, an estimated three hundred million people-a fifth of the world's population-turned on their television screens to witness a technological miracle. They watched Apollo 11 trace a path through the sky, pierce the darkness of space, and hurtle toward the lunar surface. When the American spacecraft finally descended onto the celestial body, Neil Armstrong gingerly stepped down a ladder and planted his foot on the moon's dusty regolith. Shortly after, his voice crackled through the void: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."

Back home, CBS was one of the many news outlets doing live coverage for millions of viewers. When the module touched down, and Armstrong announced that "the Eagle has landed," CBS' cameras cut back to their anchors, Wally Schirra and Walter Cronkite. At that moment, viewers saw an emotional Schirra wiping away a tear while the usually composed Cronkite bowed his head, momentarily speechless. Although the newsroom was silent, it felt as though the whole cosmos had just cheered. More than fifty years later, this moment is still one of this nation's proudest achievements.

America's giant leap to the moon required a few running steps, which took place in the form of field trips across the United States and then the world. In the years leading up to the launch, NASA decided that their astronauts needed to do fieldwork in addition to time in the classroom. They wanted them to practice collecting geological samples, identifying their positions, and getting in and out of lunar modules so that they'd build a kind of muscle memory that'd ensure a smooth mission. However, having never been to the moon, NASA's directors didn't know what to expect. So, they carefully chose a series of planetary sites they thought would approximate the moon's tectonic formations or what might be the remnants of volcanic lava flows.

Most of these analog missions took place in Hawaii and across the American Southwest. In Hawaii, NASA's astronauts studied volcanoes by getting up close to lava lakes and tubes. In one of Arizona's man-made crater fields, they tested their ability to pinpoint their location by looking out of their module's windows and comparing their topography to satellite images. Since the lunar mission required them to collect geological samples, they learned how to identify and gather rocks along the Grand Canyon, the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, and a site just east of Death Valley.

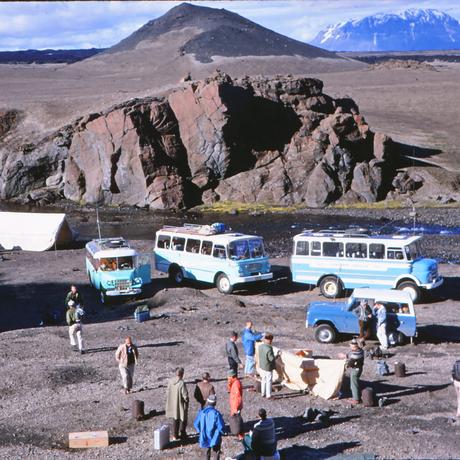

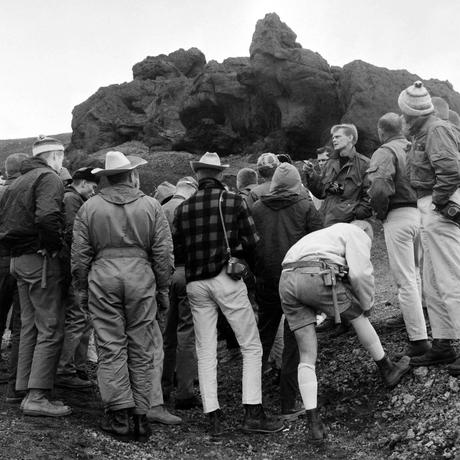

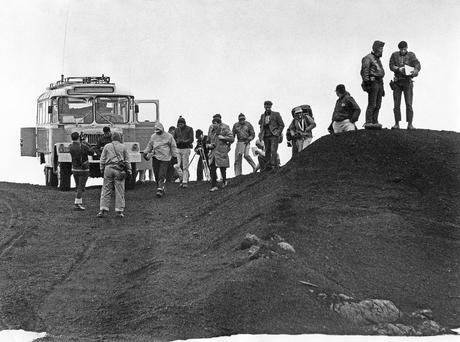

Training in the United States wasn't enough; NASA wanted their astronauts to test their skills abroad. So they sent thirty-two of their astronauts-including Armstrong-to Iceland. As an isolated Nordic island located along the mid-Atlantic ridge, it's easy to believe you've landed on another planet here. Iceland's geography is a natural bubbling laboratory full of active volcanoes and gushing geysers. It's thought that the rocky, barren highlands here are among the most moon-like surfaces on earth. If you're lucky enough to visit sometime between September and March, you can also witness the dancing Northern Lights-those shimmering green curtains that remind humans of how infinitesimal they are in the universe.

For this fieldwork, NASA scouted a quiet 2,300-population fishing community known as Húsavík, located on Iceland's northern coast. According to the 13th-century Book of Settlements , a Swedish Viking named Garðar Svavarsson set sail in 860 A.D. to claim an inheritance from his father-in-law. After his ship was blown off course and he was forced to circumnavigate the island, he landed in a small bay, later known as Skjálfandi. Garðar stayed here for just one winter before setting sail again in the spring, but upon his departure, three people-a crewman named Náttfari and two slaves-escaped in a smaller boat. The three set up a farm using Garðar's homestead and later moved further inland. This was the founding of Húsavík.

Not much is known about Náttfari's origins or fate. He may have been a slave himself, and while his name isn't Norse, it's believed that it may translate to "Night Traveler." A passage from the Book of Settlements suggests why his story may have been largely omitted: "[...] we think we can better meet the criticism of foreigners when they accuse us of being descended from slaves or scoundrels if we know for certain the truth about our ancestors." So, early Icelandic historians wrote more of men such as Ingólfr Arnarson, a Norseman of higher class status who killed two Irish slaves to avenge the death of his brother. Ingólfr's journey to Iceland seemed more heroic, as he famously "threw his high seat pillars overboard and promised to settle where the gods decided to bring them ashore." This was the founding of Iceland's capital, Reykjavík. Of course, it's natural to write more about the founder of Iceland's largest and most important city. Still, the passage suggests that early Icelandic historians were sensitive about the idea that some Icelanders descended from enslaved people-no matter how heroic those people may have been-and thus were reluctant to mention them.

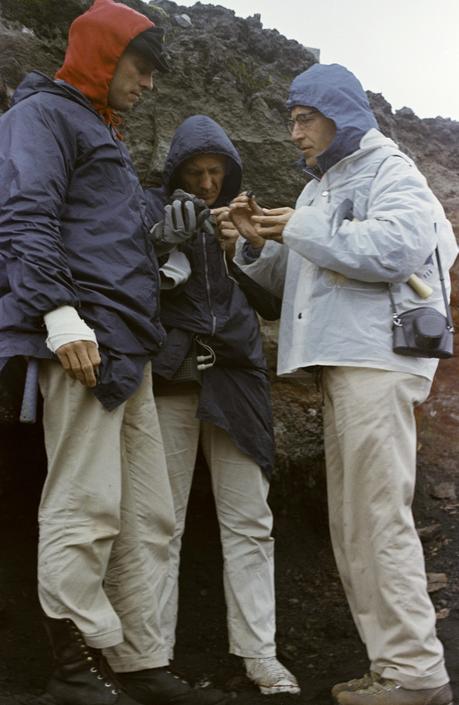

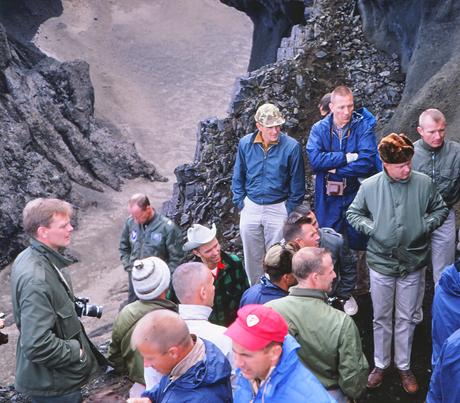

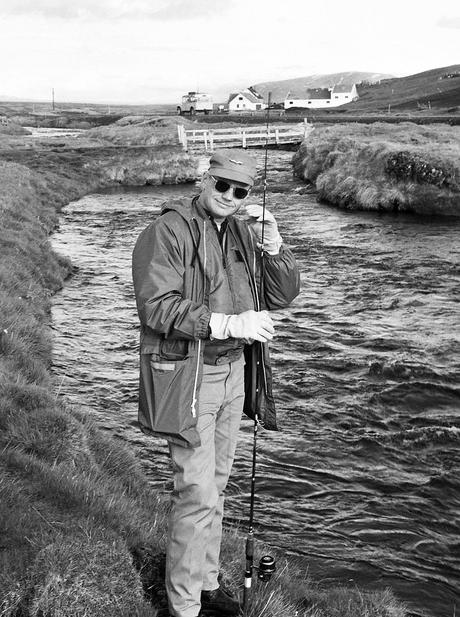

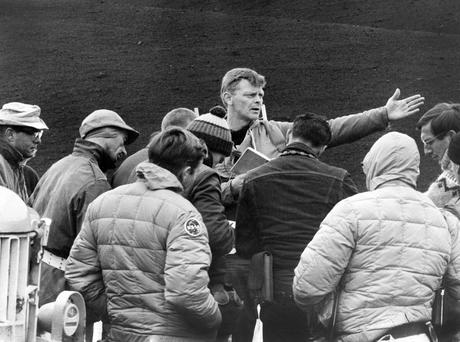

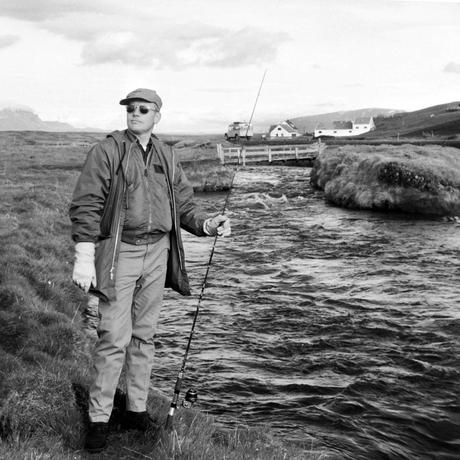

If it hadn't been for Náttfari's escape, perhaps America's trip to the moon would have been less successful. For a week in July 1965 and ten days in July 1967, thirty-two American astronauts bounded around Húsavík. They came here to become familiar with the "varied rock assemblages found in glacial outwash channels," which NASA thought might resemble the complexity of the lunar surface. "I spent around ten days exploring the volcanically active regions of Iceland, a place so stark and barren I felt as if I were already on the moon," remembered Al Worden, who went to the moon in 1971 as the command module pilot for Apollo 15. "We were there in the summertime, and it seemed like the sun never set. You could be out at 03:00 and see people strolling the city streets, the stores still open." Local sheep farmer Ingólfur Jónasson took a young Armstrong to go fishing along the banks of the Laxá í Aðaldal, a river known for its plentiful salmon. Jónasson remembered Armstrong being a "very kind man" and having "a good aura about him." However, he was not a very good fisherman. "The fish were nibbling on his lure, but he did not manage to catch any," he recalled.

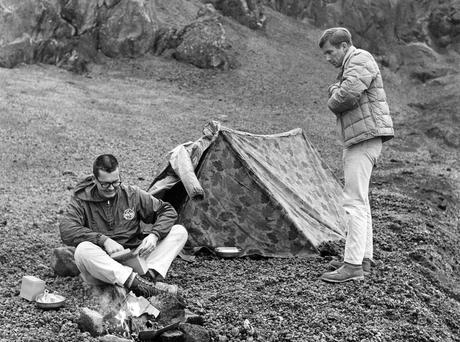

Much has been written about NASA's Apollo program, but less well-recognized is how stylish these astronauts dressed while on their analog missions. Back when he was still writing at the now sadly-defunct blog A Suitable Wardrobe, Will Boehlke often talked about the challenges of dressing for "shoulder seasons." These are the transitional months between summer and winter when the weather isn't cold enough for heavy Balmacaans or tweed jackets, but it's also not quite time for rayon or seersucker. As a man who almost exclusively wore bespoke tailoring, Boehlke recommended brown suits in gabardine, cotton, or Solaro, lightweight sport coats paired with odd vests, and Irish Poplin ties if you want a bit of sheen. These are all excellent recommendations, but what should one do for casualwear?

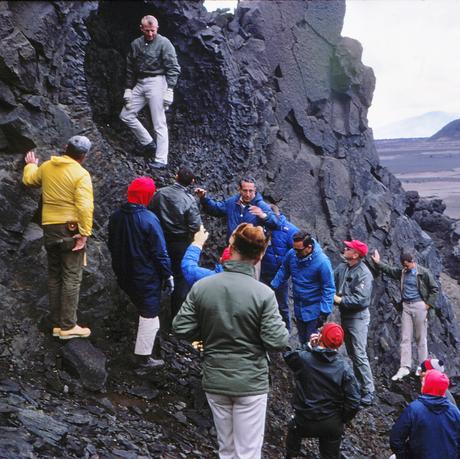

The answer may be to dress like a man preparing for a mission. In these photos, we see NASA's astronauts wearing lightweight layers with two-pocketed sport shirts, rugged work boots, and relaxed straight-legged chinos (fuller than what would be considered a slim-straight cut today). Some can be seen wearing slimmer white jeans in ways that look more utilitarian than preppy. There's also some more autumn-appropriate clothing, such as fuzzy Nordic sweaters and quilted parkas to shed incoming drizzle. But mostly, one can imagine adjusting these uniforms a little-shedding the knits and swapping the parkas for trucker jackets-for a comfortable and stylish spring ensemble.

These outfits combine the best of Americana, making them particularly well-suited for a mission that would later become a defining moment of American greatness. There's Rugged Ivy (e.g., Eddie Bauer Skyliner and Yukon jackets that one might have encountered at Dartmouth in 1965), Maine Guy or Northwestern outdoorsman (e.g., LL Bean field shirts with green plaid Sears Cruisers), California Westernwear (e.g., Levi's Type III with blue jeans and beaded necklaces), and good old fashioned militaria (e.g., the Army jackets that countercultural youths pressed into subversive service during the 1960s and '70s). There's also an unabashed love for silly hats: late 1940s-style aviator caps, jaunty berets, fur trapper caps, cowboy hats, and beanies with pom poms. There's something charming about a man willing to wear a silly hat.

You can check out much of this history at The Exploration Museum in Húsavík, which has exhibits covering Viking exploration, Arctic explorers, and NASA's time in Iceland (the photos here are from the museum). If you're inspired by the clothes, here are some ways you can dress up, even if you have no space to go.

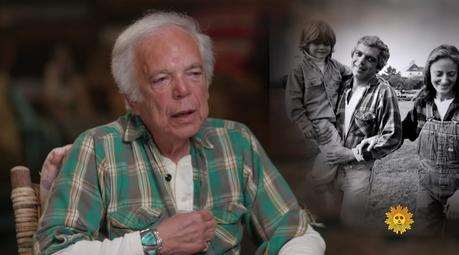

This season, I'm in love with this green plaid RRL flannel, which looks awfully similar to the one Ralph wore during a 2019 interview on CBS Sunday Morning. The flannel is special because it's the same one he wore nearly fifty years ago when Susan Wood photographed his family hanging out at their newly bought home in the Hamptons. Those iconic images captured America's heart when Ralph was then a rising name in the fashion world-and he looked just as good wearing the same exact outfit decades later on CBS Sunday Morning. "This is living proof of what I believe in," Lauren said of his slubby old flannel. "I love the aging of it, I love the rips, I love it all. I happen to like this because it's one that I have memories of. [I wore it today] because I wanted to look great." I bought the RRL version this season and have been wearing it with the Ralph Lauren jeans mentioned above.