Rachel Held Evans having a bit of fun

By Alan Bean

The title of this blog post from Rachel Held Evans reads like a dusty treatise cribbed from a little-read theological journal, but it is well worth reading. Before long there will be four posts in this series on the domestic codes of the New Testament and I urge you to read them all. (For more on the author, check out this piece from the Atlantic.)

At issue here are all those passages where Paul and a few other New Testament luminaries, make disparaging remarks about women; or at least that is how these passages are commonly read. Rachel Held Evans doesn’t mind sharing her problems with the Bible, but she believes the domestic codes are only problematic when we rip them from their original context. Fully contextualized, these passages are alive with life and blessing.

Four Interpretive Pitfalls Around the New Testament Household Codes

Rachel Held Evans

This is the first post in a weeklong series entitled “Submit One To Another: Christ and the Household Codes,” which will focus on those frequently-cited passages of Scripture that instruct wives to submit to their husbands, slaves to obey their masters, children to obey their parents, and Christians to submit to one another (Ephesians 5:21-6:9, Colossians 3:12-4:6; 1 Peter 2:11-3:22). You are welcome to join in the conversation via the comment section or by contributing to our Synchroblog. Use #onetoanother on Twitter.

***

Ever heard this before?

“The Bible says wives are to submit to their husbands, so clearly, Christian men are supposed to be the heard of the household and Christian wives are supposed to defer to the wishes of their husbands when making family decisions.”

Or this?

“The Bible teaches husbands to love their wives and wives to respect their husbands because men need respect more than they need love and women need love more than they need respect.”

Or what about this?

“The Bible says wives are to submit to their husbands and slaves to their masters, so clearly, it’s an outdated and irrelevant text that oppresses people.”

Which is typically countered with this…

“The Bible doesn’t approve slavery. What it says about slaves obeying their masters should be applied to employees and employers. But instructions to wives still stand.

When it comes to the interpretation and application of the parts of Peter and Paul’s* epistles typically referred to as the household codes, misunderstanding and controversy abound. Unfortunately, many of our assumptions about these texts emerge without an understanding of their original context or intent, which is what this series aims to address. So to start us off, I’ve identified four common interpretive pitfalls surrounding the New Testament household codes.

Before we begin, you might want to reread the texts in question in their entirety:

1 Peter 2:11-3:22

Four common pitfalls:

1. We assume the instructions found in the Peter and Paul’s Household Codes are totally unique to Scripture.

A lot of Christians are under the assumption that instructions about wives submitting to their husbands are found exclusively in the pages of Scripture, that these are solely “biblical” concepts. But the Christians in the churches at Ephesus, Colossea, and Asia Minor who first heard these letters read aloud would instantly recognize Peter and Paul’s version of the household codes as a sort of radical Christian remix of familiar Greco-Roman philosophy.

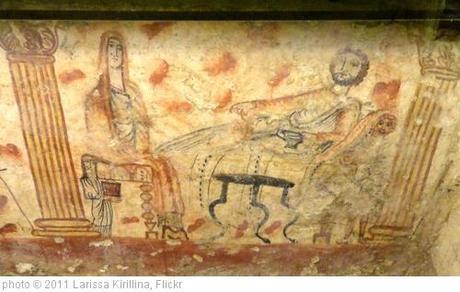

As far back as the fourth century BC, philosophers considered the household to be a microcosm, designed to reflect the hierarchal structure of the society, the gods, and ultimately the universe. Aristotle wrote that “the smallest and primary parts of the household are master and slave, husband and wife, father and children” and devoted several sections of his Politics to the importance of free men ruling over their wives, children, and slaves. First-century philosophers Philo and Josephus included the household codes in their writings as well, arguing that a man’s authority over his household was critical to the success of a society.

Many Roman officials believed the household to be such an important part of Pax Romana that they passed laws ensuring its protection. In fact, Christians were finding themselves at odds with some of these laws—particularly those governing widows—which is probably why Peter and Paul address them. How are people seeking to dismantle the divides between Jew and Gentile, slave and free, male and female supposed to live in a society where these divisions were so central to the culture and where doing so my arouse even more suspicion and persecution? This is what members of the early church were wrestling with when Peter and Paul wrote their household codes. The apostles weren’t imposing a new structure onto marriage. They were addressing a structure that already existed and instructing new believers on how to bring Christ into that structure. These passages do not introduce a new ordering of the household, but rather comment on an existing one.

You will hear me say this several times this week: The most important question we have to ask when reading the New Testament household codes is this—is their purpose to reinforce the importance of preserving the hierarchy of the typical Greco-Roman household or is their purpose to reinforce the importance of imitating Christ in interpersonal relationships, regardless of cultural familial structures? Are these passages meant to point us to Rome or to Jesus, to hierarchy or to humility?

The best way to answer these questions is to familiarize ourselves not only with the New Testament codes themselves, but also with those of Aristotle, Philo, etc. so we can observe how they are similar and how they are different. We’ll cover this in an upcoming post. But if you want to check out Aristotle’s version of the household codes ahead of time, check out Section III of Politics.

2. We quote selectively from the household codes without reading them in context (and we ignore or gloss over the parts about slavery).

In Ephesians, just before Paul tells wives to submit to their husbands, he tells all Christians—male and female—to “submit to one another out of reverence for Christ.” In a radical departure from all the other household codes of the day, he starts with mutual submission! And yet, in many churches, instructions about wives submitting to their husbands are applied literally, but instructions about husbands and wives submitting to one another get left out of the sermon.

This happens a lot. The New Testament household codes tend to get sliced and diced, not only by well-meaning preachers, but also by the chapters and verses in our Bibles. Rarely are they read, or discussed, in their entirety.

I suspect a big reason for this is that reading the household codes in their entirety puts us in the awkward position of confronting the parts about slavery. In fact, it was the issue of slavery—not gender—that first made me question what I’d been taught about how to interpret and apply these passages. Years ago, as I was looking at one of the three Bible verses that instruct wives to submit to their husbands—the one from 1 Peter that says, “Wives, in the same way submit yourselves to your own husbands” (3:1)—my inductive Bible study skills kicked in, and I dutifully looked back a few verses to see what Peter meant by “in the same way”—you know, to get some context. To my surprise, the preceding paragraph had nothing to do with the relationship between men and women, but was instead about the relationship between masters and slaves! A little more research revealed that all three of the passages that instruct wives to submit to their husbands are either preceded or followed by instructions for slaves to submit to their masters.

The implications of this pattern are astounding. For if Christians are to use these passages to argue that a hierarchal relationship between man and woman is divinely instituted and inherently holy, then, for consistency’s sake, they must also argue the same for the relationship between master and slave, for the two are inextricably linked.

And while slavery and Greco-Roman times was not the same as the slavery of the American south, don’t for a second think that this meant it was just or good. Peter specifically discusses slavery that involved harsh treatment and beatings because that was a reality for the many slaves who made up the early church. So it will not do to shrug these verses off and casually apply them to employers and their subordinates. To do so is to gloss over the ugly reality of slavery—then and now—which, as we will see, actually takes away from the power of these passages.

Reality check: The household codes have been debated by American Christians before, but it wasn’t in the context of disagreements regarding gender; it was in the context of disagreements regarding slavery in the buildup to the Civil War. The household codes became go-to texts for those arguing that the ownership of slaves was indeed biblical. Which brings us back to our central question regarding the New Testament household codes: Is their purpose to reinforce a household structure in which men rule over their wives, children, and slaves, or is their purpose to point us to attitudes that transcend a single household structure? Do these passages leave room for societies to develop beyond hierarchies between men and women, masters and slaves, or do they require that we preserve patriarchy and slavery?

Keep in mind that the same questions that divide us today divided our not-too-distant relatives in the buildup to the Civil War.

(I wrote more about this in my review of Mark Noll’s fascinating book, “The Civil War as a Theological Crisis.”)

3. We treat the household codes as marriage advice based on pop psychology, gender stereotypes, and modern cultural assumptions.

A plethora of books and seminars have been built around treating the Household Codes as God-inspired marriage advice for modern couples, often working off the statement that “God tells wives to respect their husbands because men need respect, and God tells husbands to love their wives because women need love.”

Now, I’m happy to admit that early in our marriage Dan and I benefited from many of these books and found great, applicable advice within their pages. But as helpful as these marriage books can be, they tend to work off of generalizations about men and women that may not apply to everyone (I’m a woman, and I certainly crave respect!) and they tend to gloss over cultural elements to these texts in ways that obscure their true meaning.

This happens when we impose modern-day marital dynamics onto ancient social constructs. (Like when the biblical Esther is compared by a popular pastor to a contestant on “The Bachelor” when, in reality, she was one of hundreds of women forced into the king’s harem!) As modern, Western readers, we tend to think that when Peter and Paul reference “wives,” they must be thinking of “wife” as we understand that role/ position today (we think Claire from “Modern Family”) or that when they reference “children,” they must be thinking of little kids or teenagers (we think Haley, Alex, and Luke). Roy E. Ciampa refers to this habit as identity mapping.

But families in Peter and Paul’s world didn’t look like the Dunphys. The familial structure referenced in the household codes was that of pater familias[father of the family], which positioned the man as the ruler and authority over an economic/familial unit which consisted of the ruling patriarch, his wife, children and slaves.

Marriages were typically based on economic considerations, not love, with wives holding a higher position than slaves in the household, but still functioning in many ways as the property of their husbands, who could do with them as they willed. Women were typically married as young teenagers in arrangements made by their fathers. A family in that day might very well include multiple wives, with the male head-of-house free to force slaves to satisfy him sexually as well. As Gordon Fee explains in “The Cultural Context of Ephesians 5:18-6:9″:

“In this kind of household, the idea that men and women might be equal partners in marriage simply did not exist. Evidence for this can be seen in meals, which in all cultures serve as the great equalizer. In the Greek world, a woman scarcely ever joined her husband and his friends at meals; if she did, she did not recline at table (only the courtesans did that), but she sat on a bench at the end. And she was expected to leave after eating, when the conversation took a more public turn.”

Not only would the male head-of-house have authority over his younger children, but also his grown children, who were to submit to his will even after they had families of their own. The head of house was free to beat his slaves, or wives and children, into submission. In pater familials, the father truly ruled the household, serving as lord, judge, jury (and sometimes executioner) over his subordinates.

When read with pater familias, rather than the Dunphys, in mind, we see just how radical Peter and Paul must have sounded when they instructed husbands to love their wives as much as Christ loved the church and to be willing to give their lives for them! (Or to remember that they too are slaves to Christ and have a master in heaven. Or not to provoke their children, but to be patient with them.)

How sad that words that would have sounded so liberating to those who first heard them are today so often used to oppress and silence.

So once again, we confront our central question: Is the point of the household codes to declare pater familias the only godly household structure for all of time, or is the point of the household codes to declare Jesus Christ as the example to be followed no matter societal norms?

4. We dismiss the household codes out-of-hand as irrelevant and oppressive.

A lot of readers, upon encountering instructions about wives submitting to their husbands and slaves obeying their masters, decide that since the household codes reflect societal norms unlike our own, they must therefore be irrelevant or possibly oppressive.

But as important as it is to keep the original culture and audience of the epistles in mind, these passages can still speak to us today in powerful, life-changing ways.

With the epistles of the New Testament, we are given a glimpse into how the teachings of Jesus transformed the daily lives of his first followers. While the details of instructions regarding things like head coverings, meat sacrificed to idols, slavery, and pater familias may not apply to us today, the attitudes advocated by the authors most certainly do. We need not adopt the familial structure reflected in the household codes to adopt the posture of humility that is advocated in them.

The purpose of the household codes is to point to Jesus Christ as the model for interpersonal relationships. That model transcends culture and can be applied to any household, past or present. And it is a model that, rather than reinforcing hierarchal relationships, should point us in the opposite direction—to the radical humility and servanthood of Jesus, who did not see power as something to grasp, but humbled himself and became submissive to the point of death on a cross.

From this perspective, there is much we can learn from the household codes about confronting our own privilege, keeping whatever power we may have in check, responding to our feelings of powerlessness, practicing mutual submission in our marriages, and imitating Christ in all of our interpersonal relationships. We apply the Household Codes most faithfully to our own lives, not when we use them to reinforce power structures and hierarchy, but when we use them to break those power structures down at the foot of the cross.

Ironically, complementarians (who believe hierarchal relationships between men and women should be preserved) agree with the hermeneutical premise of those who would discount the New Testament household codes as irrelevant, for they both assume that the point of these passages is to secure the Greco-Roman household structure as divinely instituted and holy, when in reality, their purpose is to point to humility, not hierarchy, as the primary Christian ethic.

…More on all of this tomorrow!

In the meantime: What have you been taught about the New Testament household codes? Have your views changed through the years? Why? What do you think a lot of Christians “miss” when reading these passages?

***

* I am aware that Pauline authorship is disputed in some of these texts, but for simplicity, will refer to Paul as the author. (This is a conversation we can have later!)

Sources:

Discovering Biblical Equality: Complemenatrity Without Hierarchy, edited by Ronald W. Pierce and Rebecca Merrill Groothuis; Colossians Remixed: Subverting the Empireby Brian J. Walsh and Sylvia C. Keesmaat; The Womens’ Bible Commentary, Expanded Edition, edited by Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ring; The Cultural Context of Ephesians 5:18-6:9 by Gordon D. Fee

See Also:

Christians for Biblical Equality (in particular the articles on submission and headship)

Aristotle’s Politics

On Treating Modern Women as Ancient Greco-Roman Wives by Roy E. Ciampa, Ph.D

Is Marriage Really an Illustration of Christ and the Church? by Kristen Rosser

The Cultural Context of Ephesians 5:18-6:9 by Gordon D. Fee

The Dark Side of Submission by Lee Grady

Submission in Context: Christ and the Greco Roman Household Codes

Gender & The Creation Narratives

Is Patriarchy Really God’s Dream for the World?

Is the Abolition of Slavery Biblical?

Mutuality Series