Diary entry by Linus Pauling, 1980. The text reads: “L[inus] P[auling] / Found enzymes enthralling / He was filled with glee / By Vitamin C”

Part 2 of 4As a double Nobel laureate, Linus Pauling’s recommendation that everyone ingest 1 to 4 grams of vitamin C daily developed into a media frenzy. And with time, the debate took on a distinctly political flavor, with the battle over vitamin C argued on talk shows and in press releases, rather than vindicated in the lab.

Pauling’s accusations that the medical establishment was ignoring the potentially profound benefits of vitamin C in part because of a mutually beneficial relationship with Big Pharma did not, as one might expect, go over well with many medical professionals. Indeed, his work with vitamin C was written off by many as a passing craze, and Pauling was increasingly referred to as a “kook” and a medical “quack.”

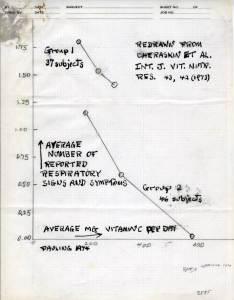

Notes by Linus Pauling regarding vitamin C and the common cold, 1974.

As Pauling and the physicians went back and forth, the two sides sometimes found themselves citing the same data and producing opposite conclusions. Often Pauling argued that the studies under consideration – discarded by dissenting physicians for apparently showing negligible effects – actually suggested a real value to the use of vitamin C that would be amplified if only larger doses were used.

One study in particular, authored in 1942 by A.J. Glazebrook and Scott Thomson, found vitamin C to only slightly decrease the occurrence of colds and their symptoms in a sample of college students. For proponents, the work was heralded nonetheless as significant evidence in vitamin C’s favor. The problem, Pauling believed, was that physicians expected vitamin C to act like a drug, with a concomitant “tendency…to use relatively small amounts and look for big effects.” But vitamin C wasn’t a drug, it was a nutrient, and Pauling thought its effects would not be easily observed in a typical physician’s research paradigm.

In an effort to put the issue to rest, a University of Maryland study in which eleven prisoners were given 3 grams of vitamin C a day for two weeks found that, when inoculated with cold viruses, each subject became ill. While many considered this proof that Pauling was wrong, he dismissed this study as well. For one, it lacked a placebo control group and did not take the severity of symptoms into account. Pauling likewise suspected that the prisoners were infected with a cold virus potent enough to have overwhelmed any protective effect from vitamin C.

On and on the debate raged and, by the time of Pauling’s death in 1994, little consensus had been reached: Pauling stood firm in his beliefs and the physicians hadn’t from their position.

Harri Hemilä

Today, while Pauling’s faith in and advocacy of vitamin C has endured in the public consciousness, it has not translated into concrete medical practice. Presently, the United States Food and Nutrition Board has set the Recommended Daily Allowance for Vitamin C at 120 mg at the highest (for pregnant women), nearly three times greater than the RDA in the 1970s, but still about 100 times lower than the levels that Pauling believed to be optimal.

So what does the research really show? Is there, in fact, zero evidence that Vitamin C prevents or cures colds, as the Food and Drug Administration once claimed?

Perhaps the best summation of the current state of affairs has been compiled by Dr. Harri Hemilä, a researcher in public health at the University of Helsinki. Hemilä, whose 2005 comprehensive study on the subject is cited by the National Institutes of Health, makes a number of intriguing points.

For one, Hemilä points out that, while the broad body of research seems to indicate that vitamin C supplementation does not decrease cold incidence in most individuals, it does significantly decrease incidence in marathon runners, skiers, and soldiers – all groups subject to consistent exposure to cold weather or physical stress – by as much as 50%. Daily supplements also appear to decrease the symptoms and duration of colds by a modest degree – observations of 14% in children and 8% in adults.

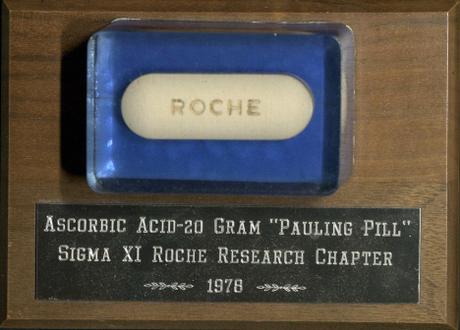

It is important to note that studies of this sort have used what Pauling would have considered to be minimum dosages for optimal health – 1 to 2 grams daily. To date, few investigations have looked into doses higher than 2 grams, presumably because it is known that, for oral doses of more than 1 gram, absorption rates fall below fifty percent. The operating idea then, is that for supplementation above 2 grams, most of the extra vitamin C is unused and excreted in one’s urine.

Yet there does exist some evidence of a more significant impact at higher dosage levels. Hemilä’s survey of the research concludes that, in some studies, doses larger than 2 grams do appear to provide some measure of therapy, if taken at the onset of cold symptoms.

Digging more deeply into the data, however, one finds conflicting results. In one study, taking 8 grams once at the onset of symptoms appeared to decrease symptoms and duration of colds. In another, 10 gram doses were given for three days during a cold, without impact.

Obviously, when trying to measure the impact of any therapy on the progression of an illness – particularly one as protean as the common cold – numerous co-factors can enter the equation. It would seem then that a thoughtful modern study of vitamin C – one that carefully considers the methodology of those conducted in the past – is still needed before we can be certain of its potential impact on the common cold.

Had Pauling invested in proving his point in the lab after the publication of Vitamin C and Common Cold, perhaps we would have a better understanding of the immune function of this nutrient today. But Pauling felt vitamin C’s protective effects against the cold were not seriously debatable and that, for him, it was time to move on. The physicians, he believed, were set in their ways – a description he often used during the long argument over vitamin C – and it was pointless for him to spend too much of his time and energy trying to disprove them.

Indeed, in Pauling’s mind, there were more important issues to take into the lab than the common cold. Because Pauling wasn’t just busy arguing that vitamin C could cure the common cold. He believed that it might cure cancer, too.