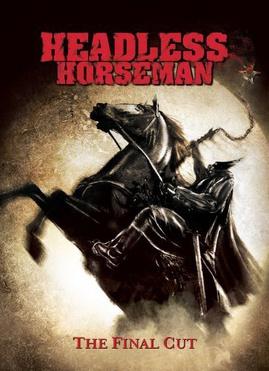

Movie quality is measured by many standards. It’s pretty clear that budgets can make a difference—Hollywood movies generally outshine television movies. Streaming services, like Netflix and Hulu, have been gaining ground here, but they still lack some of the qualia that come from long-term players in the industry. Often this was measured, pre-pandemic, by box office success. I’m not sure how it’s all quantified now, but I’m sure it still comes down to money. To me, the deciding factor about the quality of a movie is often the writing. Even with a modest budget excellent writing can make up a lot of ground. Headless Horseman originally aired on the SciFi channel (now Syfy) in 2007, and I wrote a tiny bit about it in a former post. I recently rewatched it with an eye toward how religion is integrated in it.

Headless Horseman is not a great movie. Its writing doesn’t inspire and it leaves too many gaps in the narrative to carry the viewer along easily. Still, religion plays an important role in the story. This one resets Washington Irving’s tale in the south—from the license plates, Missouri. The horseman is a serial killer who offered his victim’s heads to the hydra, the serpent that guards the entrance to Hell. When the killer is stopped and his body sent through the gateway, he comes back every seven years to chop heads. The town where all this takes place has the biblical name of Wormwood, and everyone in it is literally family. So every seven years they have to trap seven outsiders to make their offering. The person who originally stopped the killer was the local priest.

Even this brief synopsis reveals how deeply religion is engrained in this retelling. Irving’s classic story is set in an overtly religious period (particularly Protestant, of the Reformed variety), and wears this lightly. Everyone can be assumed to go to church and the Headless Horseman is a Hessian mercenary decapitated by a cannonball during the Revolutionary War. Over time, with many retellings, the horror becomes more and more involved with religion. To the point that the religion itself is the real engine of fear. A town protecting a Hell-guarding hellion doesn’t exactly make them Satanists, but it does mean they’re not far from it. The in-breeding is, however, a bit insensitive. My recent rewatching wasn’t with an eye toward the Bible, as my last viewing was. When retelling the story, however, it seems religion will surface where once it was only in the background.