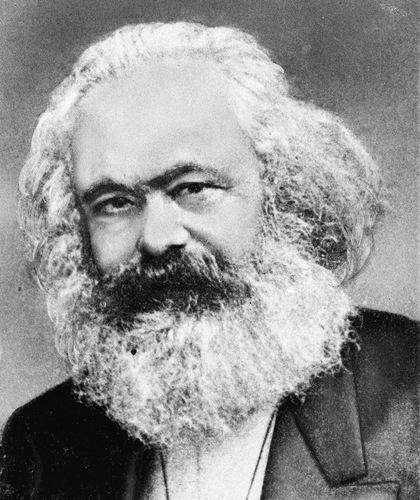

In the Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx (above) and Friedrich Engels used the German word Klassenkampfen, which translates as "class struggles." Their critics rendered it as "class warfare."

by Geoff Nunberg

——————————————————————-

.

Geoff Nunberg, the linguist contributor on NPR’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross, is the author of the book The Years of Talking Dangerously.

This transcript has been published with Professor’s Numberg written authorization. My deepest gratittude for your consent professor.

I believe all readers will connect the dots with the recent declarations from the Republican Party in regards of President Obama’s recent submission of his Labor Act to the Congress. Perhaps a little education in regards of the origin and meaning of Class Warfare will aid a few readers to understand how improper labeling is used to discredit the opponent’s initiative to justify their reaction and vote on the floor. You’ll be the judge.

.

——————————————————————-

“Class warfare” was a dodgy phrase from the outset. In one of the most famous sentences in the history of political thought, Marx and Engels wrote in their 1848 Communist Manifesto: “The history of all society up to now is the history of …”

.

That’s where things get complicated. In the original German they wrote Klassenkampfen, which means “class struggles.” But some of their critics rendered it more belligerently as “class warfare.” That was the stock label they put on the bearded socialist agitator in political cartoons. And some socialists actually did use it, while others tried to turn it around to describe the capitalist oppression of labor. But “warfare” more readily suggested the disorderly violence that broke out from below. It conjured up the red flags, cloth caps and barricades of Les Mis, not the measured operations of the parliaments and law courts on the side of the bourgeoisie.

.

It was those violent overtones that endeared “class warfare” to the right and spared it the fate of Marxist jargon like “proletariat,” “class struggle” and “the masses.” Even the left has bailed on those expressions. They’re only about a quarter as common in the pages of the New Left Review as they were in the 1970s. But “class warfare” has been on a tear in the language of the right — it’s used five times as often in The Wall Street Journal now as it was 40 years ago. In fact, the phrase has actually become more frequent as the marginal tax rates have gone down. It’s sort of a revenant, a specter that haunts the English language whenever appeals for making the rich pay more are heard in the land.

.

Like other dead metaphors, it has to be said just so. It’s “class warfare,” not “class war,” which sounds disconcertingly European, where class isn’t a forbidden subject. In a speech to a Labour Party Conference in 1999, Tony Blair famously announced, “The class war is over.” You wonder how people would have responded if Bill Clinton had said that — “What, there was a war?”

.

In fact, “class warfare” is just about the only phrase in American political discourse where “class” can appear without the all-forgiving prefix “middle.” People who level the charge of class warfare never go the logical next step to extol the virtues of class cooperation. That would imply that there actually are classes in America and would undermine the ideal of a land of opportunity. As the story goes, there are only two kinds of Americans — those who are already rich and those who expect to be. That’s why Americans won’t tolerate tax-the-rich proposals that pit one group against another, when we should be all in it together.

.

Democrats react by dismissing the charge of class warfare as a tired Republican talking point, or by trying to turn it around on the rich, the way the old Socialists did. During the 2000 election, Al Gore described the Bush tax program as “class warfare on behalf of billionaires.” But the charge does tend to put Democrats on the defensive. As President Obama said when he announced his tax program, “This is not class warfare, it’s math.” But that approach doesn’t always work in politics, where denials often are apt to raise suspicions rather than dispel them — as in “I did not have sexual relations with that woman” and “I am not a crook.”

.

Yet these days, the C-word isn’t quite as off-limits as it used to be, maybe because the populist genie has been let out of the bottle. In a speech the day after he announced his tax ideas, Obama said, “If asking a billionaire to pay the same rate as a plumber or a teacher makes me a warrior for the middle class, I wear that charge as a badge of honor.” That may be just stump speechifying, but it also makes him the first Democratic politician who has ever accepted the label and invoked the rhetoric of war against the rich.

.

The tone is different on the right, too. The Republican leadership still warn against divisiveness and avoid talking about class explicitly, other than saying that we shouldn’t be increasing taxes on the “job creators” but rather “broadening the base.” But the conservative media and bloggers have been less circumspect about cleaving society in two. Some of them talk about an all-out war between the producer class and the moocher class. And Fox Business ran a series of segments last spring called “Entitlement Nation: Makers vs. Takers.” It isn’t entirely clear who the moochers and takers are, but everybody seems to define them as including the 51 percent of American households who don’t pay federal taxes, along with those who receive Pell Grants and other forms of government assistance.

.

This isn’t just about a couple of welfare queens anymore; it carves broader than that. In fact, it recalls another famous sentence from the Communist Manifesto: “Society is splitting more and more into two enemy camps, into a face-off between two huge classes.” It’s true that Marx and Engels would have wanted to draw the line in a different place and switch around those “maker” and “taker” place cards, and of course they were rooting for a different team. Still, they all share the same basic theory of class conflict as the motor force of history. It puts me in mind of what an Italian friend of mine once said: “America, what a country! You have everything in America. You have mechanical bulls. You have early bird specials. You can even find Marxists in America.” He was right about that — and in the damnedest places, too.