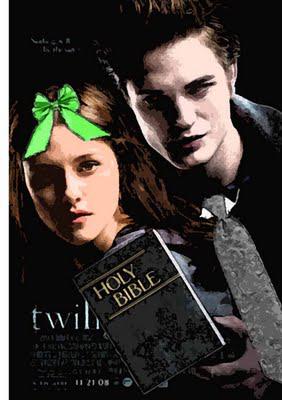

Several years ago I heard a radio personality complain that science is forever changing its position about what is healthy (aka, good) for us. They tell us that homogenized milk is bad and soy good only to recant several years later. Why can't science be wrong now? Why must it always be wrong later?Having grown up in a relatively small but active church community overseas, I am occasionally amused at the recollection of former church members I have come across two and three decades later. Once religiously enthusiastic, fresh perspectives tell of racial bigotry, relational abuse, illicit sex (Where was the sex?!), wayward children, and incontinent spouses. None of these conversations are complete, however, until the bashing of the representative head (poor pastors, elders, and bishops). Accusations range from theological heresy to pastoral incompetence to plagiarized sermons. I have always wondered about those who now claim an acute and "prophetic" awareness of past injustices when they were gung ho about it years before. Why can't their perspectives be wrong now? That goes the same for denominational solidarity on cultural issues no longer popular. I found in the home office of a dear, elderly friend a turn-of-the-20th century, black & white, 8x10 photo of a Black man hanging by his neck from a lamp post. Gathered around him (and dressed in their Sunday best) were White men, women, and children. This dear lady had a poor recollection of the photo (even though she was pushing 80), but the photo told the story. I hardly thought it a legitimate execution unless lamp posts were normally appropriated for such uses. Why were these denominational strongholds right decades ago, but wrong in retrospect?A couple of years ago I read all four books in the Twilight Saga aloud with my wife: Twilight, New Moon, Eclipse, and Breaking Dawn. While the stories did little to endear Robert Pattinson to me (even though he rocked in Remember Me and did fairly well in Harry Potter), I found Edward Cullen's character to be intriguing, especially as I grew to understand how Stephenie Meyer's Mormon beliefs figured into the development of his character. As I understand it, Edward Cullen is a member of a group of "reformed" vampires who have trained themselves to refrain from human blood. Vegetarians (but precariously so. On more than one occasion Edward is tempted to do more than just "nibble" on Bella's ear). To compound the plot, Edward falls in love with Bella (whom he actively trains not to eat). He proves to possess more self-control than the unredeemed Bella who struggles to control her sexual urge for Edward. So not only is Edward vegetarian, but he is chaste, too.Mormon belief exhibits itself in Edward's eternal devotion for Bella and in the conflict it causes between them both. Edward loves Bella so much that he is unwilling to let her be transformed into a vampire like himself so that they could be together forever in that eternal, freeze-framed sort of way. Bella, however, yearns so badly to be with Edward that she is willing to forfeit the joys of being human even to the point of being careless with her own life. Edward relents and Bella receives her glorified body (which is fit for eternal sex, another Mormon tenet).For all of the quirkiness in Mormon beliefs, something beautiful and valuable has been lifted and transformed from that very strange heritage and translated into the series. Imagine (for you women) an absolutely flawless man who is physically built and beautiful, intellectually astute and reasonable, and he has eyes for no one but you. You can't figure out why. He could easily hurt you (and you see it sometimes in his eyes), yet he loves your obvious flaws so much and gagas over your most simplistic attributes. He loves you so well that you believe him and fall for him. You have to admit there is something strongly desirable about that kind of possessive devotion, even if it is a modern version of its very chauvinistic ancestor.In order to illustrate how very difficult it is to make a religious belief palatable across a wide spectrum of beliefs, let us imagine a couple of denominational vampires. Oh, come on, it will be fun. I will give you two.VAMPIRE AThis certain vampire recognizes no other vampire save that he or she has been bit by a close relative. In fact, any victim who does not trace his lineage to said close relative might look like a vampire and bite like a vampire, but do not be fooled: none of those vampiric traits are genuine. These vampires like to immerse new vampires in vats of a special liquid, the act of which insures vampiric transformation. This vampire can be easily warded off by the playing of various instruments and especially agitated by the accompaniment of the human voice with those instruments. These vampires can be found in small groups throughout the Southeast.VAMPIRE BThis vampire traces its rites and ceremonies to a particular vampiric code, the culmination of this codification happening in the early 17th century. Interestingly, this code is traced back to certain earlier fragments considered to be talismanic for all "purebloods." Said purebloods are always vigilantly on the offense against "leeches," pretenders. This vampire operates on two fronts. On the one hand, it seeks to make new vampires as fast as possible. On the other hand, it is forever weeding out the vampires they make, attributing the "leeches" to any number of causes like inferior saliva, improper biting methods, and especially the inability of alleged (new) vampires to remember the time and day that they were bitten.Oh, I should stop while I'm ahead. My point is two-fold. First is simply that while theological one-to-one ratios do not necessarily make for good literature, it is difficult to imagine what unique beliefs of some denominations could ever be the nexus of the next, great, compelling novel. But that is what denominations are forever doing: reframing themselves to some extent within the value system of the next generation.Secondly is that vampire stories really focus on the treatment of flesh and blood, and are, therefore, little Eucharistic stories. Twilight glorifies the abstinence of flesh in deference to the fruits of a more substantial, weightier love (which is still a very physical prize). I wonder what a Baptist, Presbyterian, or Episcopalian vampire would look like. What is its belief about flesh and blood? How central is Communion to denominational life? I wonder how long the series would last. I wonder how captivated people would be. I wonder how palatable they could make it.I occasionally think about that man swinging from the lamp post. I wonder what he did. I wonder if he went willingly. I wonder how a Sunday crowd could transition from listening to a sermon to viewing a hanging to having an afternoon "fellowship." I wonder if there was laughter later that afternoon, no less than six hours after that man's last breath left him. I wonder what the sermon was about that next week. But we decry those kinds of conditions nowadays as if we and the tenets of our faith had nothing whatsoever to do with the sentiments, decisions, and actions of our ancestors. I don't necessarily know why we do that. What I do know (and this is a hard pill to swallow) is that what they did back then was right and only became wrong when most everyone who was right was dead.