What should be done about Joe Paterno’s statue?

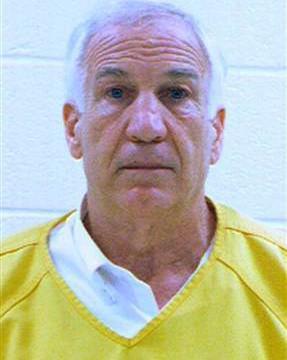

Jerry Sandusky, the former Penn State defensive coordinator, was convicted of raping at least 10 young boys.

The reputation that was groomed for so long seems to be unraveling, thread by thread.

Joe Paterno, the now-deceased football coach of the Penn State Nittany Lions, is the focus of renewed media attention after a scathing report implicated Paterno and other top university brass in a cover-up that officials say was designed to shield his football program from censure.

If you haven’t heard about Jerry Sandusky and his crimes, read about it here.

What seems clear is this: dating back to at least 1998, Paterno, Graham Spanier (Penn State President), Tim Curley (Athletic Director), and Gary Schultz (Vice President) knew about the history and severity of Sandusky’s crimes, and failed to alert authorities. Moreover, they did nothing to keep Sandusky off Penn State premises, where Sandusky raped many of his victims.

Curley, and Schultz, who previously stated that they were unaware of the extent of Sandusky’s wrongdoing, are now charged with lying to a grand jury. Both await a trial date. Spanier has not been charged.

The Freeh report draws a damning link between Penn State’s cult of football and the university’s eagerness to protect Sandusky at the expense of his victims. In the report, Paterno comes off as a dictator willing to sacrifice his morals for the greater glory of football.

Spanier, Paterno, and Curley.

Recently, much of the debate surrounding the case has been about symbolism. University officials have already renamed the tent village outside Beaver stadium “Nittanyville.” It used to be called “Paternoville,” a painful reminder of the former coach’s now-sullied legacy. The media, in its infinite wisdom, has largely focused on the issue of a Joe Paterno statue outside Beaver Stadium, and whether it should be torn down.

Bobby Bowden, the respected former football coach of Florida State, has publicly stated that the statue should come down:

Now the reason is, Penn State’s job now is to try to forget this thing. But every time somebody walks by and sees that statue, they’re not going to remember the 80 good years, they’re going to remember this thing with Sandusky. Just think, every time you go to a ballgame at Penn State and they shine a camera on that statue, that’s going to be brought up again.

Other pundits have chimed in. Rick Reilly, an ESPN columnist, said this:

What’d [Penn State officials] do instead [of calling child services]? Alerted nobody. Called nobody. And let Sandusky keep leading his horrific tours around campus. ‘Hey, want to see the showers?’ That sentence alone ought to bring down the statue.

I share the uncontroversial opinion that Sandusky’s crimes are terrifying, cruel, and display a sickening selfishness. I too want to see Spanier, Curley, and Schultz pay for their lies and inaction, if the Freeh report turns out to be true. I can’t begin to imagine what the victims and their families must be going through right now.

But I don’t believe the statue should come down. I hope my belief will not be interpreted as an apology for Paterno, Sandusky, or any of the other men involved in the scandal.

Bowden’s comments boil down to this: the statue is now a symbol of scandal, not of football, and Penn State should try to erase all associations with Sandusky, even if it means whitewashing Paterno from the family portrait.

Reilly’s logic is a little more cloudy. I think what he’s saying is that the severity of Sandusky’s crimes makes Paterno’s cover-up all the more inexcusable, and that we should not idolize people like Paterno who display deep moral failures.

Don’t mince words, and don’t worry about PR. Don’t pretend Paterno never existed, or aggressively tailor his image. Don’t assume people are too stupid to connect the dots.

The problem with Bowden’s statement is that he seems to endorse the publicist’s prerogative of pretend it didn’t happen. This seems itself to be a moral failure. What’s so wrong with “remember[ing] this thing with Sandusky?” Sure, the memory is painful. But isn’t it also necessary? According to Bowden’s calculations, Paterno’s entire football career is more deserving of our memory than his failure to turn in a serial sexual predator. I’m not so sure I agree. When Paterno is invoked, maybe people should remember the Sandusky thing instead of the football thing. Since when does football trump the safety of young lives?

Reilly advocates the wrong response for the right reasons. Although he doesn’t go out and say it, Reilly is worried about the implicit respect Paterno’s statue could command if the university fails to act. Reilly worries because he thinks Paterno had bad qualities. He’s right: every day, Paterno is looking more and more like an insensitive beast. But he’s wrong if he thinks that people will excuse Paterno’s negligence because he gave Penn State 60 years of dominance. And he’s also wrong if he thinks that History will fail to adequately condemn Paterno if the statue remains. People are not dumb. We know when to prioritize moral failings over football. A statue is indeed a symbol, but the meaning of the symbol can be reappropriated.

Paterno’s statue, outside Beaver Stadium.

Here’s my proposal to Penn State. Keep the statue up. In a very prominent place, install a plaque or a memorial detailing the crimes of Sandusky and the mistakes of Paterno. Don’t mince words, and don’t worry about PR. In fact, hire a PR black hole to make sure that any and all PR is sucked into a pocket of nothingness before it threatens to spin the facts. Don’t pretend Paterno never existed, or aggressively tailor his image. Don’t assume people are too stupid to connect the dots.

In 2008, I traveled with my friend to Auschwitz, Poland. Auschwitz was the site of one of the most infamous death camps set up by the Nazis during WWII. After the war ended, the Germans, saddled by guilt, or the Poles, saddled by grief, could have destroyed what was once a monument to prejudice, suffering, and death. It would have been easy, and it would have been quick. Some people undoubtedly— understandably—wanted to wipe the slate clean. Instead, the Polish government memorialized Auschwitz. They didn’t tinker with it. They rebuilt it as it was. They hired conservators, historians, and custodians to help tell the story of more than one million prisoners who lost their lives at the hands of a brutal regime, in a lonely little place, for a senseless cause.

The gates to the concentration camp. The sign translates as “Work sets you free.”

I will never forget what I saw in Auschwitz. I saw a room where display cases were filled with human hair, collected before and after prisoners died. I saw subterranean showers, where prisoners were pelted with cold water before being gassed with Zyklon B. I saw a medical experimentation room, where the Angel of Death infected countless twins with diseases before he butchered them in experiments.

I’m not going to sit here and suggest that Sandusky’s crimes and Penn State’s cover-up even compares to the Nazis’ pogrom against the Jews. It doesn’t. But Penn State could learn a little about preserving the past from the Polish government. In its haste to make the regrettable situation better, Penn State runs the risk of improperly acknowledging the human costs that were trampled on by powerful university leaders. The goal of Penn State should not be to simply move on, as Bowden suggests. The goal of Penn State, in my mind, is to ensure that this tragedy never happens again. Acknowledging the role that Paterno played in the tragedy is an important part of that goal. And keeping the statue is one of the most powerful reminders Penn State could give.

We’re not really sure what to feel when the meaning of a symbol is neutral, or when positives mingle with negatives. We feel about as comfortable with an ambiguously symbolic statue as we feel with an ambiguously gendered person.

The statue debate has highlighted a curious human tendency. We constantly try to simplify people, things, and ideas because we’re not very good at handling complexity. Let me explain. Before Paterno was embroiled in the Sandusky case, everyone wanted to believe that he was a god. After the Sandusky case, lots of people want to believe that Paterno was evil. But not very many people are saying, ‘Paterno was a football genius who deserves credit for revolutionizing the game, but who displayed some very suspect morals when he let Sandusky continue to rape little boys because the fallout might have hurt his team.’ People want to think of a person as either essentially good or essentially bad, and not something in-between. I think Paterno is probably an in-between.

The furor over his statue illustrates this tendency. People derive the meaning of the statue from the worth of the individual. If people feel the person in the statue is essentially good, then the meaning of statue is positive. If people feel the person in the statue is essentially bad, then the meaning of the statue is negative. We’re not really sure what to feel when the meaning is neutral, or—because “neutral” implies a lack of culpability—when positives mingle with negatives. We feel about as comfortable with an ambiguously symbolic statue as we feel with an ambiguously gendered person. People want Paterno’s statue taken down either because their estimation of Paterno’s worth has gone sour (Reilly), or because it’s turned ambiguous and they’re unsure of which factors they should weigh when deciding (Bowden).

After extreme emotional trauma, homo sapiens can sometimes turn into neanderthals.

The mold of the statue, not the meaning, is fixed in bronze. If Penn State chooses, it can leave the statue of Paterno intact, as it sits right now outside of Beaver Stadium. It can turn into a symbol of frailty and the excesses of power. It can teach a lesson about how easily a good man can do not-so-good things, or how quickly a god can fall from the heavens. The statue would renounce its role as a rally point, and assume the guise of a fable or an artifact—an artifact designed to help the school commit itself again to education and stewardship. I realize that it would be incredibly difficult for a victim of Sandusky’s, or a family member of a victim, to go to a football game and see a statue of a Paterno cast in brilliant bronze. But wishing it away is like pretending the scandal didn’t happen. While this is an appropriate knee-jerk response, I think the long-term health of a nation will be better served by taking a long look at our fallen idols, recognizing their mistakes, and asking, “What went wrong?”