Japan has had more than its fair share of epic disasters, the most recent of which came on March 11, 2011, when the earth shifted and ocean waved. Within hours, twenty thousand Japanese were dead. As might be expected, survivors were deeply shaken and sadly traumatized. And then the ghosts and spirits came, in some cases possessing people.

In this haunting story over at the London Review of Books, Richard Lloyd Parry reports on the ghosts and possessions of the post-tsunami. It’s a long story that contains many stories within it. We can get a sense for the main storyline from these paragraphs, which I have edited and spliced:

Priests – Christian and Shinto, as well as Buddhist – found themselves called on repeatedly to quell unhappy spirits. A Buddhist monk wrote an article in a learned journal about ‘the ghost problem’, and academics at Tohoku University began to catalog the stories. ‘So many people are having these experiences,’ Kaneda told me. ‘It’s impossible to identify who and where they all are. But there are countless such people, and I think that their number is going to increase. And all we do is treat the symptoms.’

When opinion polls put the question, ‘How religious are you?’, the Japanese rank among the most ungodly people in the world. It took a catastrophe for me to understand how misleading this self-assessment is. It is true that the organised religions, Buddhism and Shinto, have little influence on private or national life. But over the centuries both have been pressed into the service of the true faith of Japan: the cult of the ancestors.

The tsunami did appalling violence to the religion of the ancestors. Along with walls, roofs and people, the water carried away household altars, memorial tablets and family photographs. Cemetery vaults were ripped open and the bones of the dead scattered. Temples were destroyed, along with memorial books listing the names of ancestors over generations.

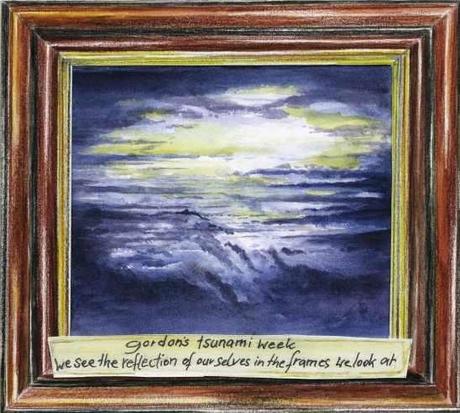

Thousands of spirits had passed from life to death; countless others were cut loose from their moorings in the afterlife. How could they all be cared for? Who was to honor the compact between the living and the dead? In such circumstances, how could there fail to be a swarm of ghosts?

Even before the tsunami struck its coast, nowhere in Japan was closer to the world of the dead than Tohoku, the northern part of the island of Honshu. In ancient times, it was a notorious frontier realm of barbarians, goblins and bitter cold. For modern Japanese, it remains a remote, marginal, faintly melancholy place, of thick dialects and quaint conservatism, the symbol of a rural tradition that, for city dwellers, is no more than a folk memory. Tohoku has bullet trains and smartphones and all the other 21st-century conveniences, but it also has secret Buddhist cults, a lively literature of supernatural tales and a sisterhood of blind shamanesses who gather once a year at a volcano called Osore-san, or ‘Mt Fear’, the traditional entrance to the underworld.

Masashi Hijikata, the closest thing you could find to a Tohoku nationalist, understood immediately that after the disaster hauntings would follow. ‘We remembered the old ghost stories,’ he said, ‘and we told one another that there would be many new stories like that. Personally, I don’t believe in the existence of spirits, but that’s not the point. If people say they see ghosts, then that’s fine – we can leave it at that.’

We should indeed leave it at that. We should never begrudge traumatized survivors their healing stories.

There are of course those who will accept these stories as something more and will take them to be statements of fact or reflections of supernatural reality. I’m guessing that many of the visitors who have been coming to this blog from Bob Cranmer’s book promotion website may believe this.

For my part, I find it curious that reports of ghosts, spirits, and possessions are always culturally specific and geographically provincial. Why do these chimera manifest in accordance with Christian constructs when they appear in Pittsburgh, but manifest in accordance with Shinto constructs when they appear in Japan?