We use coordinated rhythmic movement as our task; I've blogged this task in many posts and used this research programme as an example of theoretically driven, mechanistic modelling science. The basic form of the task is described here, the basic pattern of behavioural data is described here, and the model that implements our perception-action approach is described here. The main thing to know is that there are only a couple of rhythmic coordinations that are easy without training (0° and 180°), but other coordinations can be learned with feedback driven training. This gives us a simple model task that can serve as a window on perception-action mechanisms of skilled action and learning.

Transfer of Learning

One way to study the internal structure of a learned skill is to study whether and how that learning transfers. We expect that learning one thing will transfer to another thing to the extent that these things overlap in the way they are put together. In principle, you can use transfer to map out the relationships between a whole host of tasks. The very weird result of this work, however, is that as a general rule, learning is highly specific to the thing you practice. It does not require much of a change to almost completely remove transfer of learning. You can learn a pursuit motor tracking task at one speed but only see 37% transfer to that task at another speed. You can learn to balance on a slack-line or on a beam, and see basically no transfer. These kinds of results are why I often say things like 'there's no such thing as behaviour, only behaviours-in-contexts', and why the ecological approach includes a formal analysis of the context (e.g. task dynamics) when we try to explain behaviours. The main problem revealed by these results is that we are clearly not identifying real parts and processes when we decompose behaviours into their components. For example, there is clearly no such thing as 'balance', per se. So these studies are struggling to help us identify the parts of behaviours, and we need another way to do this (which we can then test with transfer methods).Ecological Task Dynamics

Sabrina and I have proposed (in Golonka & Wilson, 2019) that an ecological task dynamical analysis can guide us to find the real parts and processes that make up the mechanism of the behavior in question, and that we can therefore do mechanistic modelling. We used coordinated rhythmic movement as our paradigm case, specifically the work done by Bingham (and then by me too :).Bingham's model claims that coordinated rhythmic movement looks the way it does because the rhythmically moving limbs are coupled via particular perceptual information for the coordination (specifically, relative phase is specified by the relative direction of motion). In particular, moving at 90° is maximally hard because that information is maximally variable there. You can learn to do 90°, however, and I have previously shown that this entails switching to use a different variable to perceive relative phase (specifically, relative position; Wilson & Bingham, 2008, reviewed here). Finally, we then showed (Snapp-Childs, Wilson & Bingham, 2015) that this new perceptual coupling supports learning of and transfer between unimanual and bimanual versions of this task. The question in this paper was whether learning to perceive 90° via relative position can support improved performance at any other relative phases. Transfer between relative phases has never been shown but this is because those studies trained people with transformed feedback, where learning relative position was not an option. I developed a method 10 years ago to provide more appropriate augmented feedback that doesn't interfere with the task dynamic; so we tested for transfer using this method (see this post for details on the differences).Methods

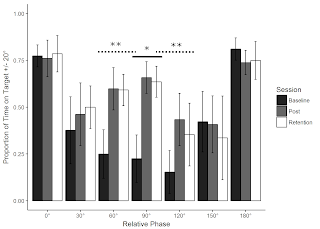

Danny extensively trained 10 people to perform 90° to a strict criterion, using my coordination feedback. He also assessed their performance at Baseline, Post-Training, and Retention (2-4 weeks later). Assessment Sessions: Participants tried to produce bimanual coordinated rhythmic movements at 0°, 30°, 60°, 90°, 120°, 150° and 180°, and he measured the stability of their movements as the proportion-time-on-target, +/-20°. He also tested their perceptual thresholds at 90° in a 2-alternative forced choice task. In Post Training and Retention, he added a perturbation judgement task, which breaks relative position as information for relative phase and let's us test whether that is what they have learned to use.Results

At Baseline, participants could do 0° and 180° reasonably well, and nothing else stably. Thresholds at 90° were high (i.e. poor); they can't do 90° because they cannot perceive it. So far, so good - looks like earlier work.At Post-Training and Retention, performance at 90° was greatly improved and perceptual thresholds were low/good (i.e. they had learned and it had stuck). After training, the perturbation condition confirmed they had all learned by switching to relative position (none of them could do the judgment task anymore if relative position could not serve as information for relative phase at 90°). Again, so far so good. Did this learning support improved performance anywhere we hadn't practiced? We assessed this with a linear contrast analysis, which is basically a way of running a one shot t-test on data from multiple conditions looking for a specific pattern. A significant result tells you the specified pattern is a good fit for the data; you can have differences across the conditions that don't fit and that would yield a non-significant result. It's a great analysis, and it preserved a lot of power by replacing the ANOVA+pairwise comparisons alternative. We found huge transfer of learning, from 90° to 60° (81% transfer!) and 120° (65%!). See Figure 1, which shows that the pattern of improvement was a good fit at these relative phases but nowhere else. Learning to perform 90° entails learning to perceive relative phase at 90° via relative position, and this variable also supports perception and performance of 60° and 120°. A reminder: this is the first time anyone has found transfer of learning across relative phases, and it's because we have correctly decomposed the task into the right real parts and processes.